Dame Alice Kyteler, born in 1263, was the first person to be condemned for witchcraft in Ireland. This case appears to be very similar with Gilles de Rais’ and appears to be more a struggle of religion, power and greed than demonic activity.

Alice’s family settled in Kilkenny in 1280. She was an only child and when her father died in 1298, she inherited his business and properties. Soon afterwards she married William Outlawe, a banker and former associate of her father who lived on Coal Market Street in Kilkenny. He was twenty years her senior.

Following the birth of their son William, Alice decided to extend their house onto St. Kieran’s Street and develop it into an inn. Alice was reportedly very good looking with the ability to manipulate men into giving her gifts and favours. As a result, the inn was frequented by many men, both young and old, who sought her attention.

Rumors about Alice performing satanic rituals and rites began around this time. Following the sudden death of her husband under mysterious circumstances, it was rumored that before his death he had forced open a press in the basement of their home. It was claimed that the cupboard contained an array of witchcraft paraphernalia, including eyes of ravens, worms, nightshade, and dead men’s hair, all cooked in a pot made from the skull of a beheaded thief.

Within months of being widowed, Alice married another banker, Adam Le Blund of Cullen, who already had a number of children. It is believed that the couple had a daughter called Basilia. In 1310 Le Blund also died suddenly and mysteriously and, like her first husband, left Alice a wealth of money and property.

In 1311, Alice married again. Her third husband, Richard de Valle, was a wealthy landlord who owned many properties in and around Clonmel. Despite being in his prime, following their marriage Richard’s health slowly began to decline. He died one evening after feasting on a lavish meal. Alice then took proceedings against de Valle’s son for withholding her widow’s dower.

In 1320, Alice married her fourth husband, Knight John Le Poer. John’s brother, Arnold, was Seneschal (governor) of Kilkenny.

Soon after the marriage, John’s health deteriorated and although only middle-aged, he became feeble. His hair turned silver and some fell out in patches, along with his fingernails (Le Poer’s symptoms would indicate that he possibly was suffering form arsenic poisoning).

John feared his declining health was his wife’s doing and approached the Friars at St. Francis’ Abbey for help. They in turn contacted the Bishop of Ossery, Richard de Ledrede.

The Bishop made numerous attempts to have Alice and her cohorts arrested but was hindered. It is claimed that her former brother-in-law, Roger Outlawe, who was Chancellor of all Ireland, used influence to prevent Alice’s arrest.

Alice wisely refused to appear and promptly left for England, returning a year later to Dublin where she urged the Archbishop to condemn the Bishop of Ossory for unlawfully excommunicating her. A showdown between the Commissioner and Bishop Lederede took place in Dublin and ended with the Bishop returning to Kilkenny from where he demanded that Alice be arrested.

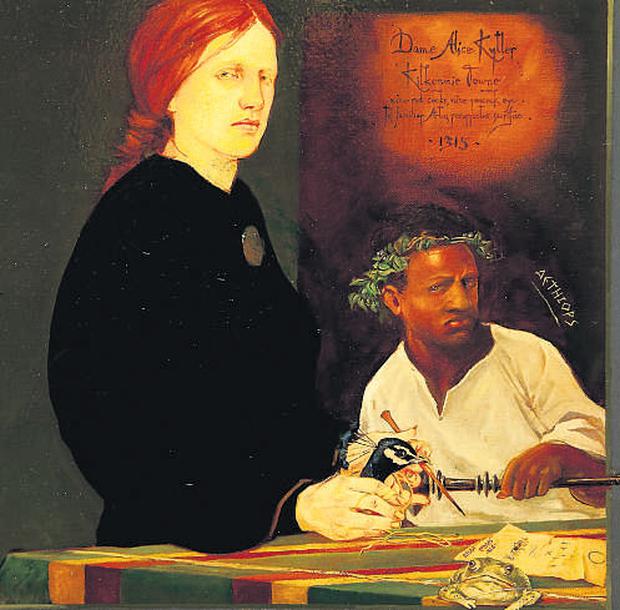

Finally in 1324 his Lordship convened a Court of Inquisition which included five Knights and several Noblemen, though Alice was not present as she had fled to Dublin. After hearing the witness and suiters, Alice was found guilty of witchcraft, magic, heresy and holding a coven of witches as well as having sex with a demon called Artissen (who is sometimes depicted as Aethiops, the mythical founder of Ethiopia).

They were accused of dismembering animals at crossroads and offering the pieces to demons. They were also accused of making horrible witches’ brews, which included the entrails of roosters, worms, dead men’s fingernails, and naughty children, which they cooked in the skull of a thief. Alice would be preparing flying ointment to fly on her broomstick as well as poisons and love philtres.

Alice and her ‘coven’ of witches were excommunicated from the Church and were to be handed over to secular authorities for further punishment.

The Bishop also summoned Alice’s son to appear on charges of heresy and protecting heretics. William was friends with Seneschal Arnold Le Poer who was the lord of the liberty. To block the Bishop, Le Poer had him arrested and imprisoned in Kilkenny jail for seventeen days.

John Darcy, the Lord Chief Justice, travelled to Kilkenny from Dublin and had the Bishop released. Darcy also examined the details of the inquisition and found them to be correct. Alice and her followers were sentenced to be whipped through the streets while tied to the back of a horse and cart and Alice herself was to be burned at the stake.

Thanks to the power of the Chancellor of all Ireland, and her other powerful allies, Alice’s escape to England was organised. Her guards were beaten senseless and Dame Alice was released from the dungeons beneath Kilkenny Castle and freed from the sentence of death that hung over her. It was the year 1324 and she was never to be seen again.

William confessed to the charges against him and was imprisoned in Kilkenny Castle. Under influence from William’s many powerful friends, the Bishop sentenced him to penance and released him.

The Kilkenny Witchcraft Trials did however take place. William Outlawe was convicted and ordered by Bishop Lederede to attend three Masses every day and to give alms to the poor. He was also made to repair the roof of St. Canice’s Cathedral as punishment. This light sentence was in sharp contrast to the torture handed out to less wealthy friends of Alice, including her maid Petronella who was tortured, whipped and finally burned at the stake in front of a large crowd outside the Tholsel on the 3rd of November 1324.

William eventually covered St. Canice’s roof in lead but in 1332 the roof collapsed under the weight of it. It has been suggested that William purposely used too much lead to make it collapse in retaliation for the treatment he and his mother had received.

William Butler Yates makes reference to Alice in his poem Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen:

There lurches past, his great eyes without thought

Under the shadow of stupid straw-pale locks,

That insolent fiend Robert Artisson

To whom the love-lorn Lady Kyteler brought

Bronzed peacock feathers, red combs of her cocks.