Úlfhéðnar

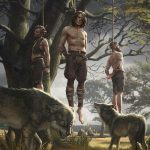

Those wearing the skins of wolves were called Úlfhéðnar (“wolf coat”; singular Úlfheðinn), another term associated with berserkers, mentioned in the Vatnsdæla saga, the Haraldskvæði and the Völsunga saga and are consistently referred to in the sagas as a type of berserkers. The first Norwegian king Harald Fairhair is mentioned in several sagas as followed by an elite guard of úlfhéðnar. They were said to wear the pelt of a wolf when they entered battle.

Úlfhéðnar are sometimes described as Odin’s special warriors: “[Odin’s] men went without their mailcoats and were mad as hounds or wolves, bit their shields…they slew men, but neither fire nor iron had effect upon them. This is called ‘going berserk’.” In addition, the helm-plate press from Torslunda depicts a scene of Odin with a berserker with a wolf pelt and a spear as distinguishing features: “a wolf skinned warrior with the apparently one-eyed dancer in the bird-horned helm, which is generally interpreted as showing a scene indicative of a relationship between berserkgang … and the god Odin”.

No fact in connection with the history of the Northmen is more firmly established, on reliable evidence, than that of the berserkr rage being a species of diabolical possession. The berserkir were said to work themselves up into a state of frenzy, in which a demoniacal power came over them, impelling them to acts from which in their sober senses they would have recoiled. They acquired superhuman force, and were as invulnerable and as insensible to pain as the Jansenist convulsionists of S. Medard. No sword would wound them, no fire would barn them, a club alone could destroy them, by breaking their bones, or crushing in their skulls. Their eyes glared as though a flame burned in the sockets, they ground their teeth, and frothed at the mouth; they gnawed at their shield rims, and are said to have sometimes bitten them through, and as they rushed into conflict they yelped as dogs or howled as wolves.

[1. Hic (Syraldus) septem filios habebat, tanto veneficiorum usu callentes, ut sæpe subitis furoris viribus instincti solerent ore torvum infremere, scuta morsibus attrectare, torridas fauce prunas absumere, extructa quævis incendia penetrare, nec posset conceptis dementiæ motus alio remedii genere quam aut vinculorum injuriis aut cædis humanæ piaculo temperari. Tantam illis rabiem site sævitia ingenii sive furiaram ferocitas inspirabat.–Saxo Gramm. VII.]

According to the unanimous testimony of the old Norse historians, the berserkr rage was extinguished by baptism, and as Christianity advanced, the number of these berserkir decreased.

But it must not be supposed that this madness or possession came only on those persons who predisposed themselves to be attacked by it; others were afflicted with it, who vainly struggled against its influence, and who deeply lamented their own liability to be seized with these terrible accesses of frenzy. Such was Thorir Ingimund’s son, of whom it is said, in the Vatnsdæla Saga, that “at times there came over Thorir berserkr fits, and it was considered a sad misfortune to such a man, as they were quite beyond control.”