In Greek mythology, Charon (Greek Χάρων, fierce brightness) was the ferryman of Hades, the Greek underworld, (Etruscan equivalent: Charun) and the son of Erebus and Nyx. Dante Alighieri incorporated Charon into Christian mythology in his Divine Comedy. He is the same as his Greek counterpart, being paid an obolus to cross Acheron.

Role

Charon is a traditional psychopomp figure who take the newly dead from one side of the river Acheron (sometimes the river Styx) to the other. To cross into the realm of Hades, the souls had to go across the River Acheron. The only way to safely do so was on Charon’s ferry. Corpses in ancient Greece were always buried with a coin underneath their tongue to pay Charon. Those who could not pay had to wander the banks of the Acheron for one hundred years.

Some mortals, heroes and demigods (Odysseus, Heracles, Orpheus, Psyche, Aenas) were said to have descended to the underworld and returned from it as living beings. This journey is known as catabasis, and those who undergo it may acquire partial or full immortality, either through persuasion or payment of another, more exceptional fee. To pay for his entry to Hades as a living mortal, Virgil’s Aeneas gives Charon the Golden Bough.

According to Virgil’s Aeneid (book 6), the Cumaean Sibyl directs Aeneas to the golden bough necessary to cross the river while still alive and return to the world.

Trojan, Anchises’ son, the descent of Avernus is easy.

All night long, all day, the doors of Hades stand open.

But to retrace the path, to come up to the sweet air of heaven,

That is labour indeed.

— Aeneid 6.126-129.

Origin

Charon is first attested in the now fragmentary Greek epic poem Minyas, which includes a description of a descent to the underworld and possibly dates back to the 6th century BC.

However, the ancient historian Diodorus Siculus thought that the ferryman and his name had been imported from Egypt. One of the most common scenes of the Egyptian afterlife was of a boat making its way through the Underworld. It was helmed by Osiris, the dead king of the gods.

In Virgil’s epic poem, Aeneid the dead who could not pay the fee, and those whose had received no funeral rites, had to wander the near shores of the Styx for one hundred years before they were allowed to cross the river.

Description

The name Charon is most often explained as a proper noun from χάρων (charon), a poetic form of χαρωπός (charopós) ‘of keen gaze’, referring either to fierce, flashing, or feverish eyes, or to eyes of a bluish-gray color. The word may be a euphemism for death. Flashing eyes may indicate the anger or irascibility of Charon as he is often characterized in literature, but the etymology is not certain.

Charon is depicted frequently in the art of ancient Greece. Attic funerary vases of the 5th and 4th centuries BC are often decorated with scenes of the dead boarding Charon’s boat. On the earlier such vases, he looks like a rough, unkempt Athenian seaman dressed in reddish-brown, holding his ferryman’s pole in his right hand and using his left hand to receive the deceased. Hermes sometimes stands by in his role as psychopomp.

The Etruscans associated him with one of their own chthonic gods. He took on many of this god’s attributes including graying skin, tusks, a hooked nose, and a heavy mallet in his hands.

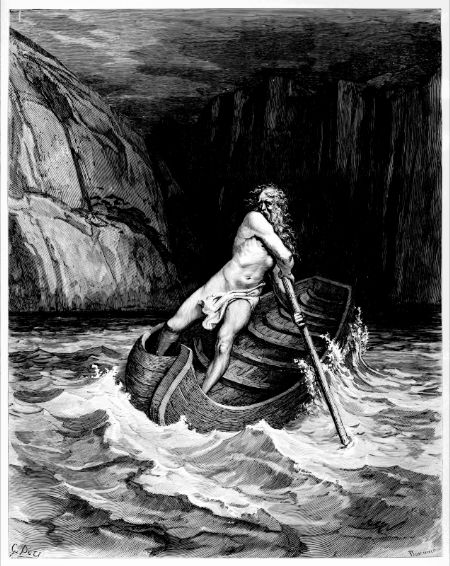

In the 1st century BC, the Roman poet Virgil describes Charon, manning his rust-colored skiff, in the course of Aeneas’s descent to the underworld (Aeneid, Book 6), after the Cumaean Sibyl has directed the hero to the golden bough that will allow him to return to the world of the living:

There Charon stands, who rules the dreary coast –

A sordid god: down from his hairy chin

A length of beard descends, uncombed, unclean;

His eyes, like hollow furnaces on fire;

A girdle, foul with grease, binds his obscene attire.

Other Latin authors also describe Charon, among them Seneca in his tragedy Hercules Furens, where Charon is described in verses 762–777 as an old man clad in foul garb, with haggard cheeks and an unkempt beard, a fierce ferryman who guides his craft with a long pole. When the boatman tells Heracles to halt, the Greek hero uses his strength to gain passage, overpowering Charon with the boatman’s own pole.

In the second century, Lucian employed Charon as a figure in his Dialogues of the Dead, most notably in Parts 4 and 10 (“Hermes and Charon” and “Charon and Hermes“).

In the 14th century, Dante Alighieri described Charon in his Divine Comedy, drawing from Virgil’s depiction in Aeneid 6. Charon is the first named mythological character Dante meets in the underworld, in Canto III of the Inferno. Dante depicts him as having eyes of fire. Elsewhere, Charon appears as a mean-spirited and gaunt old man or as a winged demon wielding a double hammer, although Michelangelo’s interpretation, influenced by Dante’s depiction in the Inferno, shows him with an oar over his shoulder, ready to beat those who delay (“batte col remo qualunque s’adagia”, Inferno 3, verse 111).

In modern times, he is commonly depicted as a living skeleton in a cowl, much like the Grim Reaper. The French artist, Gustave Dore, depicted Charon in two of his illustrations for Dante’s Divine Comedy.