Aka: Danse macabre, Danza macabra, Todtentanz

The French term Danse Macabre may derive from the Latin Chorea Machabæorum, literally “dance of the Maccabees.”

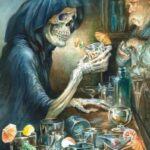

A favorite medieval theme, connected with the view of the world as mere vanity, was the leveling of all social classes and ranks in death, with the latter aptly personified as the bare, unidentifiable, universal skeleton.

Description

The typical form which the allegory takes is that of a series of pictures, sculptured or painted, in which Death appears, either as a dancing skeleton or as a shrunken, shrouded corpse, to people representing every age and condition of life, and leads them all in a dance to the grave. The number of characters and the composition of the dance may vary according to time, place and purpose of the artist, 24 being a popular figure

The dances of death are to be found on the outside walls of cloisters, cemeteries, in mortuary chapels, ossuaries and even in churches. Of the numerous examples painted or sculptured through medieval Europe few remain except in woodcuts and engravings.

The dance of death often takes the form of a farandole. There are words exchanged between death and its victims which are painted as verses below the corresponding pictures. The death speech is threatening , cynical, or sarcastic while the man cries for mercy in a last attempt to save his life. Everyone gets into the dance: from the whole clerical hierarchy (pope, cardinals, bishops, abbots, canons, priests), to every single representative of the laic world (emperors, kings, dukes, counts, knights, doctors, merchants, usurers, robbers, peasants, and even innocent children). Death does not care for the social position, nor for the richness, sex, or age of the people it brings into its dance.

Death is often represented with a musical instrument. Music has always been associated with the various death and life rituals. Music provides an enchantment, the passage from Earth to the unknown. The Sirens were great musicians, Orpheus delivered Eurydice from Hades thanks to his beautiful songs.

The “Dance of Death” was also a species of spectacular play. The oldest traces of these plays are found in Germany, but we have the Spanish text for a similar dramatic performance dating back to the year 1360, “La Danza General de la Muerte”. We read of similar dramatic representations in Bruges before Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy in 1449.

Signification

The deathly horrors of the 14th century such as recurring famines, the Hundred Years’ War in France, and, most of all, the Black Death, were culturally assimilated throughout Europe. The omnipresent possibility of sudden and painful death increased the religious desire for penance, but it also evoked a hysterical desire for amusement while still possible; a last dance as cold comfort. The Danse Macabre combines both desires: in many ways similar to the medieval mystery plays, the dance-with-death allegory was originally a didactic dialogue poem to remind people that they all will die, without exception and that a grim saraband of skeletons, lurks around to take them away. (see memento mori and Ars moriendi).

Origin

The origin of this allegory in painting and sculpture is disputed. It occurs as early as the 14th century, and has often been attributed to the overpowering consciousness of the presence of death due to the Black Death and the miseries of the Hundred Years War.

It has also been attributed to a form of the Morality, a dramatic dialogue between Death and his victims in every station of life, ending in a dance off the stage. The origin of the peculiar form the allegory has taken has also been found in the dancing skeletons on late Roman sarcophagi and mural paintings at Cumae or Pompeii, and a false connection has been traced with the Triumph of Death, attributed to Orcagna, in the Campo Santo at Pisa.

The dance of death of the Cimetière des Innocents in Paris, painted in 1424, is considered the starting point of this pictural tradition. The theme of Death seizing all men from emperors to peasants became popular during all the 15th century and there were numerous dances of death painted across Europe. Unfortunately, few have survived the centuries. There are also traces of theatral plays that were played in the same fashion.

The dance of death was preceded and prepared by a literary genre called Vado Mori (I prepare myself to die) in vogue during the 13th century. They includes short sentences (like haiku) of people from various strolls of life who are going to die. The most popular were the king, the pope, the bishop, the knight, the physicist, the logician, the young man, the old man, the rich, the poor and the insane.

In the 15th century, there was also a poetic genre in Spain that featured dialogs between death and human characters. The most famous, Dança generale de la Muerte, includes 33 characters.

There are also numerous German woodcut versions. In 1523–26 the German artist Hans Holbein the Younger made a series of drawings of the subject, perhaps the culminating point in the pictorial evolution of the dance of death, which were engraved by the German Hans Lützelburger and published at Lyon in 1538. Holbein’s procession is divided into separate scenes depicting the skeletal figure of death surprising his victims in the midst of their daily life. Apart from a few isolated mural paintings in northern Italy, the theme did not become popular south of the Alps.

In the nineteenth century the motif was re-energized by revolution and social upheaval, and heralded the arrival of a social fantastic with Alfred Rethel’s great series. The theme continued to inspire artists and musicians long after the medieval period, Schubert’s string quartet Death and the Maiden (1824) being one example. In the twentieth century, Ingmar Bergman’s 1957 film The Seventh Seal has a personified Death, and could thus count as macabre.