What is a ritual?

Any formal and customarily repeated act or series of acts. A ritual can be the established form for a ceremony, a system of rites, a ceremonial act or action.

The power of a ritual comes from the faith that the individual has in their ability to provide meaning.

Rituals should not be confused with beliefs and attitudes. While rituals are constantly under threat of being leveled down, beliefs evolve and modernize in accordance with changes in human interpretation due to their complexity and dynamic character.

The 3-D rituals

A person is not fully dead, Hertz argues, until the proper rituals have been completed. These rituals, he asserts, must effect transitions at three levels of meaning and experience. The corpse, the soul of the deceased, and society at large all have their status thrown into question by death, and funeral rituals must resolve the ambiguities in a situation where they are not, in fact, fully resolvable, though humans often wish they were, and wish that we could truly know the answers to the mystery of death.

The body of a deceased person, the first of Hertz’s foci of attention, is prepared for final disposition in different ways in different cultures. It is significant, however, that all cultures, including contemporary North America, include some special treatment for a body however promised to dust.

The soul of the deceased, almost universally, is said to be helped by funeral rituals to assume whatever character and mode of existence its culture deems appropriate for the spiritual aspect of a person, the part that neither decomposes nor burns, and is widely regarded as leaving the physical remains after death.

The fate of society. Not only the survivors must be given modes of coping with whatever personal loss they may feel, but adjustments in social roles, some of them quite far ranging, must be made. Someone must assume the dead person’s status and inherit titles and property. Widows or widowers must change their marital status, and, in most societies must be made available to new partners. Death rituals provide the bereaved with a final chance to make it right by the deceased and thus provide a sense of continuity as well as final closure. As with all rites of passage, these disruptions have the potential to challenge social norms and social structure.

Main functions of rituals

Death rituals provide the same benefits in every society. The differences will be in how the formal acts are performed and to which extent plays the relationship between the three parties: the dead, the family and the community.

- Provide the last rite of passage for the dead.

- Confirm and reinforce the reality of the death and separation of the living and the dead.

- Assist in acknowledging and expressing feeling of loss and facilitating mourning.

- Stimulate recollections of the deceased and help validate the deceased person’s life

- Allow participation of the community in memorializing the person who died.

- Provide the comfort and other benefits of ritual.

- Provide means for the community to give and receive social and spiritual support.

- Begin the process of helping the bereaved back into the community.

- Help in the search for meaning.

- Affirm the social order.

- Remind the living of their own and others’ mortality.

- Furnish means and method in disposing of the body.

- Change the identity of the person from living to dead.

- Transform the bereaved into their new identities.

- Allow for public acknowledgment for private grief.

- Provide meaning for loss.

They formalize a naturally occurring transition from life to death, providing a structure which facilitates the adaptation of the bereaved, whether this means accepting the permanent departure of a loved one from this life, or restoring the balance upset by the death. In a concrete sense, death rituals can also recreate social order by communicating, through the rules of who does what in the rituals, who is now to take the place of the deceased.

Death rituals also serve as tools for humankind to transform death from a defeat of life to a stepping stone to another, perhaps better, place, and thus create a continuity beyond death itself. Finally, death rituals give the bereaved one last opportunity to make amends and say “I love you” and “goodbye.” However one may choose to interpret death rituals, they constitute a dramatization of a worldly event, death, in the presence of and in reference to the sacred. The socially prescribed rituals from the time of death until the end of the mourning period are designed to provide a structure for the grief process. In reality, a culturally proper funeral is more than an empty gesture to the dead, it helps the living to grieve and go on with life.

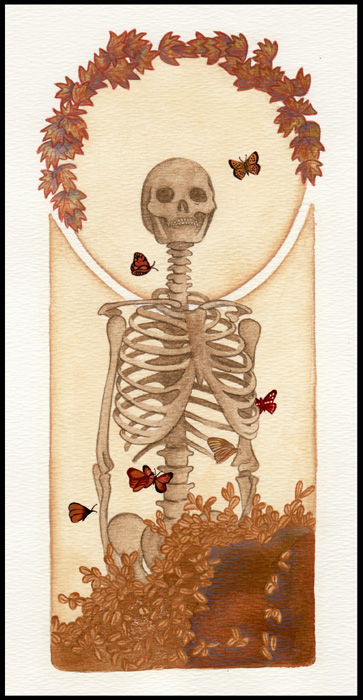

Rites of passage

Symbolic death rituals often are part of rites of passage marking other kinds of transitions. In these cases, death and rebirth are symbols for leaving one state and being reborn into another. Death rituals themselves, of course, must of necessity deal with death, but in this case the death is real, not a symbol. Rodney Needham has said that death is unique among rites of passage in the fact that we can never know the final state the dead enter at the end of the ritual, despite the tendency of funerals to refer, through words or symbols, to whatever local beliefs exist concerning the ultimate fate of the dead.

David Hicks’s , “Making the King Divine: A Case Study in Ritual Regicide from Timor” actually discusses a ritual in which a symbolic (not a real) death is used as a symbol for another change of state. This ritual, which is performed at the end of the dry season, centers upon the simulated sacrifice of a man specially chosen to impersonate a king, in order to bring fertility to humans, crops, and aquatic food sources. This ritual is interesting because the real death of divine kings has frequently been a subject of much ritual, upon which the fertility of the land was dependent. What is interesting in this case is that the “king” is “sacrificed” not because he is perceived as weak and in need of replacement, but because he is strong, and the water creatures are perceived as weak and in need of renewal. This ritual is also interesting insofar as it is a conscious reenactment of a myth; a number of theorists around the turn of the century thought all rituals had their origin in myth. In this ritual, as in many rites of passage, several transitions are made to stand for each other: the symbolic death marks the change of the seasons, which, in turn is associated with a return of fertility.

David Hicks’s, “Return to the Womb” is an example of the symbolic uses of “birth” and “death” in ritual. In this ritual a genuine death has taken place, but the final act of the funeral is a symbolic reversal of the birth which started the life which is now ended. Hicks states that the general theme of the ritual is the separation of the living survivors, especially the widow or widower from the body and soul of the deceased, so that the survivors can remain on earth, and the separation of the body and soul from each other, to be sent to separate resting places. The soul must go to join the other souls, while the body is lowered into the earth, which is seen as a symbolic womb, through an opening seen as a symbolic vagina. At one stage in the ceremony, the widow or widower fights to keep possession of the corpse, but must be separated from it, and the patrilineal kin (agnates) and in-laws of the deceased act out the parts of takers and givers of life, respectively. At one point in the ceremony the pallbearers on either side of the body have a mock battle; mock battles are not uncommon in rites of passage, especially weddings and funerals. In the ritual described in this article, we have a detailed account of a ritual of death which is a particularly good illustration both of Van Gennep’s stages of separation, transition and incorporation and Hertz’s three part schema for death rituals: the parallel passage of body, soul, and survivors from the pre-death to the post-death state.