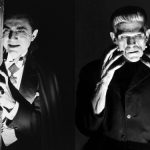

Frankenstein and Dracula both deal with the issues of death and resurrection, creation and transgression, and the blurring of the boundaries between life and death. This common linkage with death and resurrection increased with time. James Whale emphasizes the significance of digging in a Christian cemetery in his Frankenstein (1931). The pronounced crucifix and an image of the Grim Reaper reinforce the taboos associated with violating sacrosanct burial grounds. These are recurring elements in the vampire original and modern myth but they are only suggested in Shelley’s work.

In Dracula, the necessity of ridding the world of the monster is even greater than in Frankenstein, and dominates more of the textual space. By the end of both novels, the threats that the monsters pose have been overcome. But they live on in myth and in metaphor because the issues of so-called monstrosity that they address are still relevant in the post-tech world.

This raises the question of whether any links be found between the two texts. There is little doubt that Stoker had read Frankenstein by the time he wrote Dracula. After his death in 1912 his library, which was auctioned at Sotheby’s, included a copy of Mary Shelley’s novel. Indeed, in a letter to her son soon after the publication of his masterpiece, his mother said, “No book since Mrs. Shelley’s Frankenstein … has come near yours in originality, or terror.”

Stoker’s novel contains numerous resonances of Frankenstein, for they both draw upon a common stock of narrative and thematic conventions.

Both monsters attempt to invade the intellectual space of the “civilized” world. The Monster in Frankenstein reads Western literary texts (Plutarch, Goethe and Milton) in order to understand us, while Count Dracula studies English magazines to assist in the process of assimilation. Both texts use geographically identifiable landscapes for symbolic purposes. Shelley’s land of ice and snow is a counterpart to the iciness of abandonment and rejection.

Both Frankenstein and Dracula contain references to Coleridge’s famous Gothic poem “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” It is not surprising to find allusions to the poem in Frankenstein, for Mary Shelley heard Coleridge read it when she was a child. However, there are numerous parallels: layers of narrative, compulsive telling of tales, Promethean journeys, images of ice and snow, the torture of isolation and the question of guilt. Direct allusions include a stanza from the poem (58). As he runs away from the Monster he has created, Victor Frankenstein recalls:

My heart palpitated in the sickness of fear; and I hurried on with irregular steps, not daring to look about me:

Like one who, on a lonely road,

Doth walk in fear and dread,

And, having once turned round, walks on,

And turns no more his head;

Because he knows a frightful fiend

Doth close behind him tread. (59)

Scholars point to a “family resemblance” which includes a link to historical figures (Vlad the Impaler, the alchemist Dippel). Radu Florescu draws attention to a fortuitous historical “connection” between Frankenstein and Dracula. The burial ground of the Evangelical Church in the Transylvanian city of Sibiu contains a number of ancient crypts, including that of Vlad Tepes’ son Mihnea, who was assassinated in 1510. Not too far away, he states, lies the crypt of a Saxon nobleman whose name was “Baron Frank von Frankenstein” (In Search of Frankenstein, 16).

We may add also a concern with transcending the limits of what is scientifically possible (the boundaries between life and death), a portrayal of the monsters as both dignified and pitiable, a suspenseful final chase, and the structure of multiple narrations. Like dark twins, they embody “the war between science and superstition — Apollo and Dionysus at the Saturday matinee” ( David Skal, The Monster Show, 351).

On the surface, both works are horror novels which revolve around the necessity of destroying a monster. A closer examination shows that many of the qualities which define the monsters are a consequence of the way in which their stories have been passed on to us. Both authors filter their antagonist’s stories through the narratives of characters whose biases are readily apparent.

Frankenstein is constructed from three different narrations. Victor’s story includes the Monster’s narrative, while both of these viewpoints are enclosed in Walton’s letters to Margaret. The most important consequence of this textual appropriation is that, with the exception of the closing remarks over Victor’s corpse, the Monster’s story is embedded in Victor’s text. Thus, Victor asserts his authority over the Monster’s side of the story.

But there are also major differences that set apart each work and associated monster.

While Victor’s text comes to us through Walton, there are crucial differences in how their stories are filtered. Victor has editorial authority over Walton’s notes. At one point, he “asked to see them, and then himself corrected and augmented them in many places” (175). A second major difference is that Victor is speaking to a kindred spirit who has embraced him as friend and who shares a similar Promethean ambition. In contrast, Victor is a reluctant listener to the Monster’s tale, and has formed various conclusions about the speaker before hearing his story.

Victor also attempts to control Walton’s response to the Monster’s text, for he clearly wants Walton (and ultimately, us) to repudiate the Monster. Walton’s momentary sympathy for the creature is overshadowed by Victor’s warnings about its powers of eloquence and persuasion. The deck is stacked. In spite of his professions of remorse, Victor never abandons his conviction that he has acted nobly. He continues to justify his right, not only to create but to destroy what he has created. In addition, his refusal to share the secret of his creation is a major cause of the catastrophes that befall his loved ones.

In addition to posing a sexual threat, Dracula is also the supernatural Other, the undesirable challenge to educated, rational Englishmen who privilege science over medieval, pre-Enlightenment irrationality. Dracula is a destroyer rather than a preserver of text; unlike Shelley’s Monster who keeps Victor’s notebook, Dracula destroys any records he finds. This reinforces his image as the antithesis of civilized Western European culture — the cultural, social, racial, and biological Other. On the other hand, Frankenstein is a product of our Society, Science and Culture; even if he can be considered as a failure, a freak, he is the son of his time contrarily to Dracula who comes from a distant past.