There are many gods and goddess that are related to Death. Some are specifically in charge of the dead souls whereas other will carry out specific tasks such as the judgment or the migration.

Most time, the belief in Afterlife is based on the existence of kingdoms like Heaven, Hell or the Purgatory. Such places are ruled by the gods who apply their own set of rules. Below is the list of the most famous gods of Death.

More about the Headless Horseman on Monstropedia, the encyclopedia of all monsters

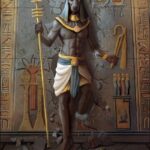

Anubis (Egypt)

Description

In art, he was usually depicted as a man with the head of a jackal and alert ears, often wearing a ribbon, and wielding a whip. On very rare occasions, Anubis was shown fully human, or slightly more frequently as fully jackal. However, Anubis was also depicted as black, rather than brown, the colour of jackals, since black was the colour that the body turned as a result of mummification.

Dogs and jackals often loitered at the edges of the desert, especially near the cemeteries where the dead were buried; in fact, it is thought that the Egyptians began the practice of making elaborate graves and tombs in order to protect the dead from desecration by jackals. In consequence, Anubis was usually thought of as a jackal, an association reinforced by certain variations of his hieroglyph, which can be translated as young dog. Thus, ancient Egyptian texts say that Anubis, like a jackal, silently walked through the shadows of life and death and lurked in dark places, watchful by day as well as by night.

Role

As ruler over the dead, Anubis was given titles such as He who is set upon his mountain, in reference to his sitting atop desert cliffs to guard multiple necropolis, and Chontamenti (also spelt Khentimentiu, and Khentamenti), meaning Lord of the Westerners, in reference to Egyptian belief that the entrance to the underworld was towards the west, since that was the direction in which the sun set. As ruler, he was also said to have been victorious over the dark forces (described as nine bows), which also, naturally, lurk in the underworld, gaining him the title Jackal ruler of the bows.

As king of the underworld, he was also considered to be the one who weighed the heart of the dead against the feather of Maàt (the concept of truth), gaining him the title He who counts the hearts. One of the reasons that the ancient Egyptians took such care to preserve their dead with sweet-smelling herbs was that it became believed Anubis would check each person with his keen canine nose. Only if they smelled pure would he allow them to enter the Kingdom of the Dead.

Family

Originally, in the Ogdoad system, he was god of the underworld, and his name is frequently thought to have reflected this, meaning something like putrefaction. He was said to have a wife, Anput (who was really just his female aspect, her name being his with an additional feminine suffix: the t), who was depicted exactly the same, though feminine. His father was originally said to be Ra, as he was the creator god, and thus his mother was said to be Hesat, Ra’s wife, who later was identified as Hathor (to whom her identity was remarkably similar). As lord of the underworld, Anubis was identified as the father of Kebechet, the goddess of the purification of bodily organs due to be placed in canopic jars during mummification.

Anubis in modern culture

- Anubis appears in the TV show Stargate SG-1 as a highly powerful and hostile “Half-Ascended” Goa’uld. He is deemed the most evil of them all, committing such atrocities that even the Goa’uld could not tolerate.

- In the MMORPG RuneScape the God Icthlarin is similar to Anubis

- Anubis is featured in the movies The Mummy, The Mummy Returns and The Scorpion King.

- Anubis appears as ‘Mister Jacquel’, who co-owns a funeral parlor in Cairo, Illinois with Thoth (as ‘Mister Ibis’) in Neil Gaiman’s novel American Gods.

- Anubis: Jackal God Of Death is the name of a 1997 album by Ganesha (band).

- Anubis appears in an episode of the animated TV series Gargoyles.

- Anubis is the focus of a series of erotic furry comic books produced by Radio Comix.

- Anubis is a primary character in Stephen King’s made-for-TV adaptation of Lars von Trier’s series Kingdom Hospital.

- The Pokémon named Lucario is visually based on the image of Anubis

- Anubismon is a Digimon in the Digimon collectible card game based on Anubis.

- Anubis is a character in Yu-Gi-Oh! The Movie. In that movie he was depicted as an evil entity wanting to take over the world, and he had the Pyramid of Light, one of the Millennium Items. He is also depicted on various cards in the Yu-Gi-Oh! Trading Card Game.

- Anubis appears in several computer games such as War Gods, Zone of the Enders, Broken Sword 3 and Gex 3.

- Anubis is the name of a space ship that appears in the Microsoft PC game Freelancer. The Anubis is a heavy fighter type available late in the game from the Order. It is often remarked to be the cheapest heavy fighter in the game at 1,100 credits.

- Anubis is the main character of Unreal Championship 2, and is a high-ranking member of the Desert Legion. He enters the Liandri-hosted Ascension Rites to stop Selket’s plan.

- Anubis, together with Bastet, was the main villain of the “Nikopol trilogy” of graphic novels by cartoonist Enki Bilal.

- A Petpet on the virtual pet website Neopets is called the Anubis, and resembles a small version of the god.

- Anubis Cruger, a.k.a. Doggie Cruger, is a dog-like blue humanoid alien, commander of Power Rangers SPD and the Shadow Ranger.

- Doggy Kruger, stuffed counterpart of the previous one in Tokusou Sentai Dekaranger, serves as commander and fights as Dekamaster.

- Anubis is the name of a battlechip in the Mega Man Battle Network Series.

- In Mega Man Zero series, there is a jackal reploid boss called Anubistepp Necromancess who comes in various versions.

- Anubis appars in the cartoon Tutenstein

- Anubis is the name of a villain who turns good in the anime series Ronin Warriors

- Anubis is one of the possible minor gods to worship in the Age of Mythology PC games

- Many forms of Anubis are included in World Of Warcraft’s 1.9 patch called Ahn’Qiraj. Two Anubises guard each part of Ahn’Qiraj invasion found across Warcraft Universe

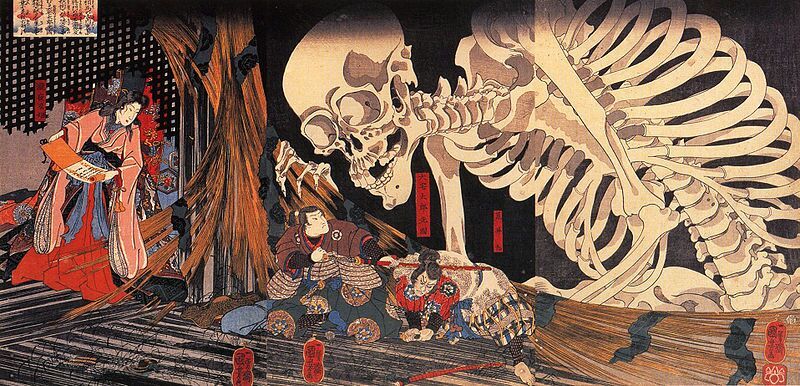

Izanami (Japan)

In Japanese mythology, Izanami (meaning “She who invites”) is a goddess of both creation and death, as well as the former wife of the god Izanagi. She is also referred to as Izana-mi, Izanami-no-Mikoto or Izanami-no-kami.

There are also death gods called Shinigami. The Shinigami are more commonly used in Japanese arts and fiction such as anime, and manga. Shinigami are briefly mentioned in the Shinto religion but are said to not actually exist.

Another popular death personification is Enma (Yama), also known as Enma Ou and Enma Daiou (Enma King, Enma Great King — translations of Yama Raja). He originated as Yama in Hinduism, later became Yanluo in China, and Enma in Japan. Enma rules the underworld, which makes him similar to Hades, and he decides whether someone dead goes to heaven or to hell. A common saying parents use in Japan to scold children is that Enma will cut off their tongue in the afterlife if they lie.

Story

The first gods summoned two divine beings into existence, the male Izanagi and the female Izanami, and charged them with creating the first land. To help them do this, Izanagi and Izanami were given a spear decorated with jewels, named Amenonuhoko (heavenly spear). The two deities then went to the bridge between heaven and earth, Amenoukihashi (floating bridge of heaven), and churned the sea below with the spear. When drops of salty water fell from the spear, they formed into the island Onogoro (self-forming). They descended from the bridge of heaven and made their home on the island. Eventually they wished to be mated, so they built a pillar called Amenomihashira and around it they built a palace called Yahirodono. Izanagi and Izanami circled the pillar in opposite directions, and when they met on the other side, Izanami spoke first in greeting. Izanagi didn’t think that this was the proper thing to do, but they mated anyhow. They had two children, Hiruko (watery child) and Awashima (island of bubbles) but they were badly-made and are not considered deities.

They put the children into a boat and set them out to sea, then petitioned the other gods for an answer as to what they did wrong. They were told that the male deity should have spoken first in greeting during the marriage ceremony. So Izanagi and Izanami went around the pillar again, and this time, Izanagi spoke first when they met, and their marriage was then successful.

From their union were born the ohoyashima, or the eight great islands of the Japanese chain: Awazi, Iyo (later Shikoku), Ogi, Tsukusi (later Kyushu), Iki, Tsusima, Sado, Yamato (later Honshu). Note that Hokkaido, Chishima, and Okinawa were not part of Japan in ancient times. They bore six more islands and many deities.

Izanami died giving birth to the child Kagutsuchi (incarnation of fire) or Ho-Masubi (causer of fire). She was then buried on Mt. Hiba, at the border of the old provinces of Izumo and Hoki, near modern-day Yasugi of Shimane Prefecture. So angry was Izanagi at the death of his wife that he killed the newborn child, thereby creating dozens of deities.

Izanagi lamented the death of Izanami and undertook a journey to Yomi (“the shadowy land of the dead”). Quickly, he searched for Izanami and found her. At first, Izanagi could not see her at all for the shadows hid her appearance well. Nevertheless, he asked her to return with him. Izanami spat out at him, informing Izanagi that he was too late. She had already eaten the food of the underworld and was now one with the land of the dead. She could no longer return to the living.

Izanagi was shocked at this news but he refused to give in to her wishes of being left to the dark embrace of Yomi. While Izanami was sleeping, he took the comb that bound his long hair and set it alight as a torch. Under the sudden burst of light, he saw the horrid form of the once beautiful and graceful Izanami. She was now a rotting form of flesh with maggots and foul creatures running over her ravaged body.

Crying out loud, Izanagi could no longer control his fear and started to run, intending to return to the living and abandon his death-ridden wife. Izanami woke up shrieking and indignant and chased after him. Wild shikome (foul women) also hunted for the frightened Izanagi, instructed by Izanami to bring him back.

Izanagi burst out of the entrance and quickly pushed a boulder in the mouth of the cavern that was the entrance of Yomi. Izanami screamed from behind this impenetrable barricade and told Izanagi that if he left her she would destroy 1,000 residents of the living every day. He furiously replied he would give life to 1,500.

The story has both strong parallels, and significant differences, with the Greek Myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, and the Maya Myth of Itzamna and Ix Chel. The Shikome, for instance, are parallel to the Maenads who tore Orpheus to pieces.

Mictlantecuhtli (Mexico)

In Aztec mythology, Mictlantecuhtli (“lord of Mictlan”) is the god of the dead and King of Mictlan (Chicunauhmictlan), the lowest section of the underworld.

Mictlantecuhtli is depicted as a blood-spattered skeleton or a person wearing a toothy skull. His headdress is decorated with owl feathers and paper banners, and he wears a necklace of human eyeballs.

Mictlantecuhtli’s wife is Mictecacihuatl, and together they dwell in a windowless house in Mictlan and rule over the dead. Mictlanteculhtli is associated with spiders, owls, bats, the eleventh hour, and the northern compass direction.

The twin gods Quetzalcoatl and Xolotl stole the bones of the previous generation of gods from Mictlanteculhtli. The death god pursued, and although they escaped, they dropped the bones, which shattered and became the various races of mortals.

Mot (Middle-East Africa)

Mot (Phoenician: 𐤌𐤕 mūt, Hebrew: מות māweṯ, Arabic: موت mawt) was the ancient Canaanite god of death and the Underworld. He was worshiped by the people of Ugarit, and by the Phoenicians.

In Ugaritic Mot ‘Death’ (spelled mt) is personified as a god of death. The word is cognate with forms meaning ‘death’ in other Semitic languages: Hebrew moth or maveth; with Canaanite, Egyptian Aramaic, Nabataean, and Palmyrene mwt; with Jewish Aramaic, Christian Palestinian Aramaic, and Samaritan mwt’; with Syriac mautā; with Mandaean muta; with Akkadian mūtu; with Arabic maut; with Ge’ez mot. Although Semetic languages are not considered related to Indo European, Sanskrit the root word for death in Sanskrit is ‘Mrit’, and Latin ‘Mortus’ is also very similar.

Origin

Mot was produced, which some say is mud, and others a putrescence of watery compound; and out of this came every germ of creation, and the generation of the universe. So there were certain animals which had no sensation, and out of them grew intelligent animals, and were called “Zophasemin,” that is “observers of heaven”; and they were formed like the shape of an egg. Also Mot burst forth into light, and sun, and moon, and stars, and the great constellations.

Story

Mot ‘Death’, son of El, according to instructions given by the god Hadad (Ba‘al) to his messengers, lives in a city named hmry (‘Mirey’), a pit is his throne, and Filth is the land of her heritage. But Ba‘al warns them:

that you not come near to divine Death, lest he made you like a lamb in his mouth,(and) you both be carried away like a kid in the breach of his windpipe.

Hadad seems to be urging that Mot come to his feast and submit himself to Hadad.

Death sends back a message that his appetite is that of lions in the wilderness, like the longing of dolphins in the sea and he threatens to devour Ba‘al himself. In a subsequent passage Death seemingly makes good his threat, or at least is deceived into believing he has slain Ba‘al. Numerous gaps in the text make this portion of the tale obscure. Then Ba‘al/Hadad’s sister, the warrior goddess ‘Anat, comes upon Mot, seizes him, splits him with a blade, winnows him in a sieve, burns him in a fire, grinds him between millstones and throws what remains on the field for the birds to devour.

But after seven years Death returns, seeking vengeance for the splitting, burning, grind and winnowing and demanding one of Ba‘al’s brothers to feed upon. A gap in the text is followed by Mot complaining that Ba‘al has given Mot his own brothers to eat, the sons of his mother to consume. A single combat between the two breaks out until Shapsh ‘Sun’ upbraids Mot, informing him that his own father El will turn against him and overturn his throne if he continues. Mot concedes and the conflict ends.

In Sanchuniathon also Death is son of El and counted as a god, as the text says in speaking of El/Cronus:

… and not long afterwards he consecrated after his death another of his sons, called Muth, whom he had by Rhea

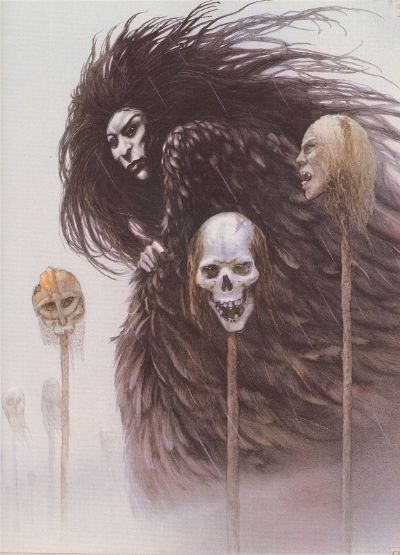

Mórrígan (Celtic Europe)

The Mórrígan (“great queen”) or Morrígan (“terror” or “phantom queen”) (aka Morrígu, Mórríghan, Mór-Ríogain) is a figure from Irish mythology widely considered to be a goddess or former goddess.

She is usually seen as a terrifying figure, glossed in medieval Irish manuscripts as equivalent to Alecto of the Furies, or the child-eating monster Lamia, from Greek Mythology (in fact, another text glosses Lamia as “a monster in female form, i.e. a Morrígan”), or the Hebrew demoness Lilith. She is associated with war and death on the battlefield, sometime appearing in the form of a carrion crow, premonitions of doom, and with cattle. She is often considered a war deity comparable with the Germanic Valkyries, although her association with cattle also suggests a role connected with fertility and the land.

She is often interpreted as a triple goddess, although membership of the triad varies: the most common combination is the Mórrígan, the Badb and Macha, but sometimes includes Nemain, Fea, Anann and others

Etymology

There is some disagreement over the meaning of the Mórrígan’s name. It can be straightforwardly interpreted as “great queen” (Old Irish mór, great; rígan, queen); however it often lacks the diacritic over the o in the texts. Alternatively, mor (without diacritic) may derive from an Indo-European root connoting terror or monstrousness, cognate with the Old English maere (which survives in the modern English word “nightmare”) and the Scandinavian mara. This theonym appears to be derived either from Proto-Celtic *Māro-rīganījā meaning “great queenly [spirit]” or else from *Moro-rīganījā meaning “nightmarish queenly [spirit]”.

There have been attempts to link the Arthurian witch, Morgan le Fay, with the Mórrígan. Morgan first appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Vita Merlini (The Life of Merlin) in the 12th century. However, the etymologies proposed do not seem

Origins

Ulster Cycle

Her earliest appearances are in stories of the Ulster Cycle, in which she has an ambiguous relationship with the hero Cúchulainn. In Táin Bó Regamna (the Cattle Raid of Regamain), he challenges her, not realizing who she is, as she drives a heifer from his territory, and earns her enmity. She makes a series of threats, and foretells a coming battle in which he will be killed. She tells him, enigmatically, “I guard your death”.

In the Táin Bó Cuailnge queen Medb of Connacht launches an invasion of Ulster to steal the bull Donn Cuailnge; the Mórrígan appears to the bull in the form of a crow and warns him to flee. Cúchulainn defends Ulster by fighting a series of single combats at fords against Medb’s champions. In between combats the Mórrígan appears to him as a young girl and offers him her love, but he spurns her. In response she intervenes in his next combat, first in the form of an eel who trips him, then as a wolf who stampedes cattle across the ford, and finally as a heifer leading the stampede, just as she had threatened in their previous encounter. However Cúchulainn wounds her in each form and defeats his opponent despite her interference. Later she appears to him as an old woman bearing the same three wounds that her animal forms sustained, milking a cow. She gives Cúchulainn three drinks of milk. He blesses her with each drink, and her wounds are healed.

In one version of Cúchulainn’s death-tale, as the hero rides to meet his enemies, he encounters the Mórrígan as an old woman washing his bloody armour in a ford, an omen of his death. Later in the story, mortally wounded, Cúchulainn ties himself to a standing stone with his own entrails so he can die upright, and it is only when a crow lands on his shoulder that his enemies believe he is dead.

Mythological Cycle

The Mórrígan also appears in texts of the Mythological Cycle. In the 12th century pseudohistorical compilation Lebor Gabála Érenn she is listed among the Tuatha Dé Danann as one of the daughters of Ernmas, granddaughter of Nuada.

The first three daughters of Ernmas are given as Ériu, Banba and Fódla. Their names are synonyms for Ireland, and they were married to Mac Cuill, Mac Cécht and Mac Gréine, the last three Tuatha Dé Danann kings of Ireland. Associated with the land and kingship, they probably represent a triple goddess of sovereignty. Next come Ernmas’s other three daughters: the Badb, Macha and the Mórrígan. A quatrain describes the three as wealthy, “springs of craftiness” and “sources of bitter fighting”. The Mórrígan’s name is said to be Anann, and she had three sons, Glon, Gaim and Coscar. According to Geoffrey Keating’s 17th century History of Ireland, Ériu, Banba and Fódla worshipped the Badb, Macha and the Mórrígan respectively, suggesting that the two triads of goddesses may be seen as equivalent.

The Mórrígan also appears in Cath Maige Tuireadh (the Battle of Mag Tuired). She keeps a tryst with the Dagda before the battle against the Fomorians. When he meets her she is washing herself, standing with one foot on either side of a river. After they have sex, the Morrígan promises to summon the magicians of Ireland to cast spells on behalf of the Tuatha Dé, and to destroy Indech, the Fomorian king, taking from him “the blood of his heart and the kidneys of his valour”. Later, we are told, she would bring two handfuls of his blood and deposit them in the same river (however, we are also told later in the text that Indech was killed by Ogma).

As battle is about to be joined, the Tuatha Dé leader, Lug, asks each what power they bring to the battle. The Mórrígan’s reply is difficult to interpret, but involves pursuing, destroying and subduing. When she comes to the battlefield she chants a poem, and immediately the battle breaks and the Fomorians are driven into the sea. After the battle she chants another poem celebrating the victory and prophesying the end of the world.

In another story she lures away the bull of a woman called Odras, who follows her to the otherworld via the cave of Cruachan. When she falls asleep, the Mórrígan turns her into a pool of water.

Nature and functions

The Mórrígan is often considered a triple goddess, but her supposed triple nature is ambiguous and inconsistent. Sometimes she appears as one of three sisters, the daughters of Ernmas: the Mórrígan, the Badb and Macha. Sometimes the trinity consists of the Badb, Macha and Nemain, collectively known as the Mórrígan, or in the plural as the Mórrígna. Occasionally Fea or Anu also appear in various combinations. However the Mórrígan also frequently appears alone, and her name is sometimes used interchangeably with the Badb, with no third “aspect” mentioned.

The Mórrígan is usually interpreted as a “war goddess”: W.M. Hennessey’s “The Ancient Irish Goddess of War,” written in 1870, was influential in establishing this interpretation. Her role often involves premonitions of a particular warrior’s violent death (suggesting a link with the Banshee of later folklore).

It has also been suggested (notably by Angelique Gulermovich Epstein in her dissertation War Goddess: The Morrígan and Her Germano-Celtic Counterparts) that she was closely tied to Irish männerbund groups (described by Máire West in her article “Aspects of díberg in the tale Togail Bruidne Da Derga”, Zeitschrift für Celtische Philologie vol. 49-50, p. 950 as: “…bands of youthful warrior-hunters, living on the borders of civilized society and indulging in lawless activities for a time before inheriting property and taking their places as members of settled, landed communities,”) and that these groups may have been in some way dedicated to her. If true, her worship may have resembled that of Perchta groups in Germanic areas.

However, Máire Herbert has argued that “war per se is not a primary aspect of the role of the goddess”, and that her association with cattle suggests her role was connected to the earth, fertility and sovereignty; she suggests that her association with war is a result of a confusion between her and the Badb. She can be interpreted as providing political or military aid or protection to the King – acting as a Goddess of Sovereignty, not necessarily a war goddess.

The Fulacht na Mór Ríoghna, the hearth or cooking pit of the Mórrígan, in County Tipperary suggests an association with the home or possibly with hunting. The Dá Chich na Morrigna or two paps of the Mórrígan, a pair of hills in County Meath, suggest a role as an earth goddess, comparable to Danu/Anu, who has her own paps in County Kerry.

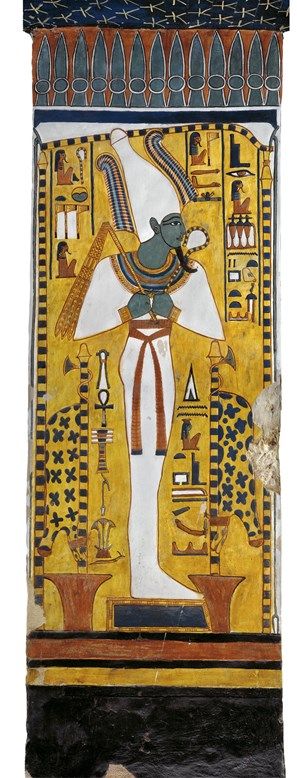

Osiris (Greek language, also Usiris; the Egyptian language name is variously transliterated Asar, Aser, Ausar, or Ausare) is the Egyptian God of the dead and the underworld.

Osiris is first mentioned in the 4th Dynasty, though it is regarded as highly plausible that he may have evolved from the god Andjety. The origin of Osiris’ name is a mystery, which forms an obstacle to knowing the pronunciation of its hieroglyphic form. The majority of current thinking is that the Egyptian name is pronounced aser where the a is the letter ayin (i.e. a short ‘a’ pronounced from the back of the throat as if swallowing).

Osiris (Egypt)

Description

In art, since he was representative of death, Osiris was usually depicted as a mummified man, with a beard, and, as ruler of the underworld, was also given the symbols of kingship – the crown, flail, and crozier. Usually, he also was depicted as having green skin, a reference to rotting flesh, and thus to death. Alternatively, the green color could also recall the color of new vegetation in Osiris’ capacity of renewing life, similar to his nightly resurrection by Re.

The main visible source of decomposition, of rotting flesh, is its consumption by insects, beetles, and other small animals. Since these animals are the prey of centipedes, centipedes became seen by the Egyptians as protecting the dead, and consequently, in Heliopolis, became thought of as an aspect of Osiris, the lord of the dead. In this form, he was known as Sepa (also spelt Sep), meaning centipede, being depicted either as a normal centipede or as a mummified figure with two horns, reflecting both Osiris’ role as lord of the dead, and the prominent horn-like Antennae exhibited by centipedes. Since centipedes are venomous, Sepa was seen as having authority over snake bites and scorpion stings, and so was invoked for protection against these things.

Because centipedes usually roam around soil, Sepa was also associated with the Earth, and his actions seen to improve its fertility. In consequence, Sepa was sometimes depicted with the head of a donkey, a major symbol of soil fertility due to the beneficial effects, to soil, of manure from donkeys in particular (horse manure would be more notable, but horses were not present in Egypt then).

Role

In the first mentions of Osiris, he was regarded the god of the underworld and the dead in the Ennead version of Egyptian mythology. At the height of the ancient Nile civilization, Osiris was regarded as the primary deity of a henotheism. Osiris was not only the merciful judge of the dead in the afterlife, but also the underworld agency that granted all life, including sprouting vegetation and the fertile flooding of the Nile River. Beginning at about 2000 B.C. all men, not just dead pharaohs, were believed to be associated with Osiris at death.

Family and avatars

He was one of the four children of the earth (Geb) and the sky (Nuit), and was the husband of Isis (Aset), who represented life. Every Khu, an aspect of the soul, seeking admission to Aaru, the Egyptian paradise, was referred to as an Osiris. As god of the dead, Babi, the god who devoured unworthy souls, was described as his first-born son.

Since Osiris was considered dead, as lord of the dead, Osiris’ soul, or rather his Ba, was occasionally worshipped in its own right, almost as if it were a distinct god, especially so in the Delta city of Mendes. This aspect of Osiris was referred to as Banebdjed (also spelt Banebded or Banebdjedet, which is technically feminine) which literally means The ba of the lord of the djed, which roughly means The soul of the lord of the pillar of stability. The djed, a type of pillar, was usually understood as the backbone of Osiris, since the Egyptians had associated death, and the dead, as symbolic of stability. As Banebdjed, Osiris was given epithets such as Lord of the Sky and Life of the (sun god) Ra, since Ra, when he had become identified with Atum, was considered Osiris’ ancestor, from whom his regal authority was inherited.

Ba does not, however, quite mean soul in the western sense, and also has a lot to do with power, reputation, force of character, especially in the case of a god. Since the ba was associated with power, and also happened to be a word for ram in Egyptian, Banebdjed was depicted as a ram, or as Ram-headed. A living, sacred ram, was even kept at Mendes and worshipped as the incarnation of the god, and upon death, the rams were mummified and buried in a ram-specific necropolis.

In Mendes, they had considered Hatmehit, a local fish-goddess, as the most important god/goddess, and so when the cult of Osiris became more significant, Banebdjed was identified in Mendes as deriving his authority from being married to Hatmehit. Later, when Horus became identified as the child of Osiris (in this form Horus is known as Harpocrates in greek and Har-pa-khered in Egyptian), Banebdjed was consequently said to be Horus’ father, as Banebdjed is an aspect of Osiris.

In contemporary occult fiction, Banebdjed is often called the goat of Mendes, and identified with Baphomet; the fact that Banebdjed was a ram (sheep), not a goat, is apparently overlooked.

Book of the Dead prayers

In the Book of the Dead there are a series of funerary formulas addressed almost exclusively to Osiris, to be learned by a man when living or inscribed on his coffin so he might enter the “blessed abodes” after death. Only those initiated into the Osirian cult would know its doctrines and ceremonials, for these were, according to the Book of the Dead, “an exceedingly great mystery…in the handwriting of the god himself…. And these things shall be done secretly” (in the rubric accompanying Ch. CXXXVIIa). The Greeks, who also copied these sacred writings, declared it a sacrilege to reveal the rites or doctrines of the mysteries. Herodotus, Plutarch and Pausanias all noted that they were not allowed to repeat what they had learned from Egyptian religious rituals. The Osirian Myth is, however, fully retold by Plutarch (Isis and Osiris, 12-20) and elaborated and reinforced by Diodorus Siculus (Library of History I, 11-27).

Osiris in popular culture

- Albert Pike (the grand commander of Freemasonry) worshipped Osiris and he proudly made that known in his book, Morals and Dogmas.

- In Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute, the priests in the Temple of Wisdom worship Osiris and Isis. The chief priest, Sarastro, sings an aria beginning “O Isis und Osiris”.

- Osiris is a deity used more than once in the hit television show Buffy the Vampire Slayer. In the show, Osiris is described as the “keeper of the gate, master of all fate” and is used in resurrection rituals. He is also unique as he is seen in one episode, communicating with Willow Rosenberg as she tries to resurrect her dead lover, Tara Maclay; although names of deities are often given in spells on the show, most of the time the deity is not seen.

- Saint Dragon – The God of Osiris is one of the Three Divine Beasts, or God Cards, from the manga Yu-Gi-Oh! and its animated adaptation, Yu-Gi-Oh! Duel Monsters.

- In the show Futurama the three main characters Fry, Leela and Bender visit an Egypt-themed planet named Osiris IV.

- In the Animatrix, the Osiris is the name of the ship that is sacrificed to make sure Zion gets the information that the machines are coming.

- In the show Stargate SG-1 Osiris and other gods are represented as evil, whereas in Egyptian culture, most of them were told to be good and beneficial, in some way, to life.

- In Joss Whedon’s Firefly, Osiris is the name of the Core planet River and Simon Tam are originally from.

- In the movie Hedwig and the Angry Inch, Hediwg’s song “Origin of Love” mentions Osiris.

- In The Vampire Lestat by Anne Rice, the legend of Osiris being cut up by his brother, Set, is discussed. As the one part of Osiris unable to be found by Isis was his genitals and because he is the god of the underworld, Lestat believes him to be a vampire God, as vampires are unable to copulate.

- The Wu-Tang Clan’s (now deceased) member, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, went by the alias, Osirus. Fans would know this as he would sometimes shout on a song, “I’m the Osirus of this shit!!”

Persephone (Greek)

In Greek mythology, Persephone (Greek Περσεφόνη, Classical Greek Persephónē, Modern Greek Persefóni) was the queen of the Underworld, the Kore or young maiden, and the daughter of Demeter.

Persephone (“she who destroys the light”) is her name in the Ionic Greek of epic literature. In other dialects she was known under various other names: Persephassa, Persephatta, or simply Kore. The Romans first heard of her from the Aeolian and Dorian cities of Magna Graecia, who use the dialectal variant Proserpina.

Hence, in Roman mythology she was called Proserpina, and as a revived Roman Proserpina she became an emblematic figure of the Renaissance.

She is the central figure in the secret initiatory mystery rites of regeneration at Eleusis, which promised immortality to their awe-struck participants—an immortality in her world beneath the soil, feasting with the heroes beneath her dread gaze (Kerenyi 1960, 1967).

Description

In Greek art, Persephone/Kore is often portrayed robed, carrying a sheaf of grain, and smiling demurely with the “Archaic smile” of the Kore of Antenor.

Story

According to Hesiod’s Theogony, Persephone was the daughter produced by the union of Zeus and Demeter. “And he [Zeus] came to the bed of bountiful Demeter, who bore white-armed Persephone, stolen by Hades from her mother’s side”.

In the Olympian telling the gods Hermes, Ares, Apollon and Hephaistos, had all wooed Persephone, but Demeter rejected all their gifts and hid her daughter away from the company of the gods. She was innocently picking flowers with some nymphs—and Athena and Artemis, the Homeric hymn says—, or Leucippe, or Oceanids— in a field in Enna when he came, bursting up through a cleft in the earth; the nymphs were changed by Demeter into the Sirens for not having interfered. Life came to a standstill as the depressed Demeter (goddess of the Earth) searched for her lost daughter. Helios, the sun, who sees everything, eventually told her what had happened.

Finally, Zeus could not put up with the dying earth and forced Hades to return Persephone. But before she was released to Hermes, who had been sent to retrieve her, Hades tricked her into eating four pomegranate seeds, which forced her to return to the underworld for one month each year for every seed that she ate. In some versions, Ascalaphus informed the other gods that Persephone had eaten the pomegranate seeds. When Demeter and her daughter were together, the Earth flourished with vegetation and color, but for four months each year, when Persephone returned to the underworld, the earth once again became a barren realm of darkness. In an alternate version, Hecate rescued Persephone. In the earliest version the dread goddess Persephone was herself Queen of the Underworld (Burkert, Kerenyi).

Persephone, as Queen of Hades, only showed mercy once, because the music of Orpheus was so hauntingly sad. She allowed Orpheus to bring his wife Eurydice back to the land of the living as long as she walked behind him and he never tried to look at her face until they reached the surface. Orpheus agreed but failed, looking back at the very end to make sure his wife was following, and lost Eurydice forever.

“As she was gathering flowers with her playmates in a meadow, the earth opened and Pluto, god of the dead, appeared and carried her off to be his queen in the world below. … Torch in hand, her sorrowing mother sought her through the wide world, and finding her not she forbade the earth to put forth its increase. So all that year not a blade of corn grew on the earth, and men would have died of hunger if Zeus had not persuaded Pluto to let Proserpine go. But before he let her go Pluto made her eat the seed of a pomegranate, and thus she could not stay away from him for ever. So it was arranged that she should spend two-thirds (according to later authors, one-half) of every year with her mother and the heavenly gods, and should pass the rest of the year with Pluto beneath the earth. … As wife of Pluto, she sent spectres, ruled the ghosts, and carried into effect the curses of men.”

Santa Muerte (Mexico)

Saint Death, otherwise known as Santa Muerte or La Santísima Muerte, is an uncanonized Mexican saint who receives petitions for love, luck, and protection and the recovery of health, stolen items, or even kidnapped family members.

Although the Catholic Church refuses to acknowledge Saint Death’s existence, this figure of prayer is said to work miracles for those who pray to and adore him/her. Prisoners, petty thieves, corrupt cops and powerful drug traffickers are said to be devotees of the so-called saint. But the cult is benefiting, too, from the faith of simple working-class Mexicans who try to abide by the law but daily face the hunger, injustice, corruption and crime of Mexico’s toughest neighborhoods.

Saint Death can be either male or female: sometimes he is dressed as a grim reaper, with a scythe and scales; sometimes, Saint Death is female, dressed in a long white satin gown and a golden crown (Muerte and the related Romance words have a feminine gender). Grim Reaper statues are made in red, white, and black – for love, luck, and protection. Offerings to Saint Death include roses and tequila. Public shrines to Saint Death are adorned with red roses and bottles of tequila, and Saint Death candles burn in his/her honor. On the border between Mexico and the United States, Saint Death prayer cards, medals, and candles are made and sold to the public.

One resource indicates that the Cult of Saint Death has been around since only the 1960s; however, other research inclines one to question if Saint Death is much older. Saint Death may have his/her roots in pre-Christian beliefs of the Aztec Native Americans, under the name of Mictlantecuhtli as the god of death. Similar to other cultures around the world, pre-Christian deities in Mexico are sometimes syncretized as saints. On the other hand, in Spanish the phrase santa muerte could also be interpreted simply as “holy death.” Saint Death may simply represent a folk-religious reinterpretation of the traditional and orthodox Roman Catholic practice of prayer to receive a blessed death in a state of grace.

Her prayers, orations, and novenas contain the Trinity, and worship of Yahweh. While some view Santa Muerte as a figure of black magic, others view him/her as specifically a Catholic saint worthy of veneration.

The phenomenon is rooted in Mexico’s pre-Columbian past but also reflects its troubled present, said Homero Aridjis, a Mexican novelist whose latest book is a series of stories called “La Santa Muerte.”

The growing devotion to St. Death among the humble “shows an enormous disappointment with the establishment and with justice in Mexico. The people know there is no protection for the poor,” Aridjis said. “It also shows alienation with the Catholic Church. People are fed up with going to church and being told what to do: ‘Sit down, kneel, stand up.’ Then they get asked to give money and get nothing back.”

The Catholic Church hasn’t launched a vigorous campaign against St. Death, but it frowns on paying homage to the figure. In its publication From Faith, the church warned last November, “the devil will do anything to win devotees.”

Followers of St. Death, who affectionately call her “the skinny girl,” say they see no contradiction between being good Catholics and praying to the statue.

Thanatos (Greek)

In Greek mythology, Thanatos (θάνατος, “death”) was the personification of death (Roman equivalent: Mors), and a minor figure in Greek mythology. Thanatos was a son of Nyx (Night) and twin of Hypnos (Sleep).

In psychoanalytical theory, Thanatos is the death instinct, which opposes Eros. The concept of the “death instinct” was identified by Sigmund Freud. For Freud, Thanatos signals a desire to give up the struggle of life and return to quiescence and the grave. This should not be confused with the comcept destrudo, which is the energy of the destructive impulse (the opposite of libido).

Description

In early mythological accounts, Thanatos was seen as a very powerful figure armed with a sword, with a shaggy beard and a fierce face. His coming was marked with pain and grief. In later eras, as the transition from life to death in Elysium became a more attractive option, Thanatos was seen as a beautiful young man. Many Roman sarcophagi show him as a winged boy, much like Cupid. Thanatos is sometimes depicted as a young man carrying a butterfly, wreath or inverted torch in his hands. He sometimes has two wings and a sword attached to his belt. He appears, with Hypnos, several times on Attican funerary vases, so-called lekythen. On a sculpted column in the Temple of Artemis at Ephese (4th century BCE) Thanatos is shown with two large wings and a sword attached to his girdle.

Role

Thanatos, in bringing death, is often followed by the fates of death or Keres, who are called hounds of Hades, and are Death-spirits, devourers of life. Thanatos, they say, is subject to the MOERAE, who are the three sisters who decide on human fate; and as everybody has a portion in life, the individual fate (moira) is usually present when Thanatos comes to fetch a mortal.

Thanatos’ power only affects mortals, for the gods, being immortal, cannot be influenced by him. On account of this, Thanatos endures the hate of mortals and the immortals’ rejection.

Story

According to the mythology, Thanatos could sometimes be outsmarted. In fact, Sisyphus did so twice. When it was time for Sisyphus to die, he succeeded in chaining Thanatos up with his own shackles. While Thanatos was chained, no mortals could die, but eventually Ares released Thanatos and handed Sisyphus over to him, but Sisyphus tricked Thanatos again by convincing Zeus to allow him to return to his wife.

Thanatos may come at any time, but his intervention in the case of Alcestis, who died a vicarious death in the place of her husband, is one of his most memorable. For Apollo had obtained a special favour of the MOERAE, which was that when Admetus should be about to die, he might be released from death if someone should choose voluntarily to die for him. Thanatos then fetched Alcestis instead of her husband.

However, the gods of the Underworld dislike this curtailing and anulling their prerogatives, and consequently Thanatos did not approve of Apollo’s manipulations, and called them trickery. And when Thanatos came to fetch Alcestis, Apollo tried to persuade him to wait and grant her a long life. But Thanatos, being ruthless, refused. Heracles however, took Alcestis from him by force, but later, when his own time came, he could not defend himself.

Whiro (Maori)

This underworld god inspires people to do evil things. Whiro typically appears as a lizard, and is the god of the dead. According to Maori Religion and Mythology by Esldon Best:

“Whiro was the origin of all disease, of all afflictions of mankind, and that he acts through the Maiki clan, who personify all such afflictions. All diseases were held to be caused by these demons–these malignant beings who dwell within Tai-whetuki, the House of Death, situated in nether gloom.”

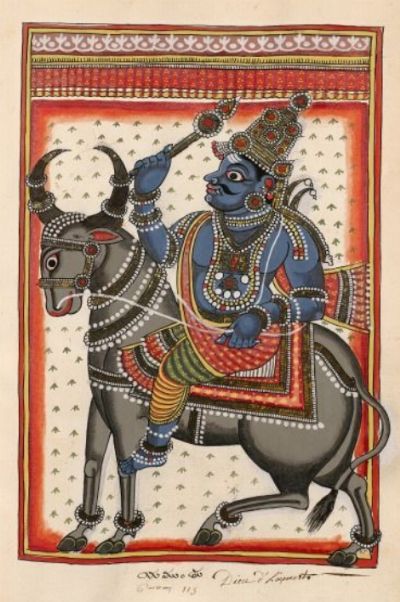

Yama (Hindus)

Yama or Yamaraja is the Hindu lord of death, whose first recorded appearance is in the Vedas. In Vedic tradition Yama was considered to have been the first mortal who died and espied the way to the celestial abodes, and in virtue of precedence he became the ruler of the departed. In some passages, however, he is already regarded as the god of death.

The seven names of Yama are: viz Yama, Dharma-raja, Mrtyu, Antaka, Vaivasvata, Kala, Sarva-pranahara.

Yama is revered in Tibet as a guardian of spiritual practice. Yama is also mentioned in the Mahabharata as a great philosopher and devotee of Sri Krishna. He is known as Yima by Zoroastrians, and is considered to be cognate with Ymir of Norse legend and has become known as Emma, or Emma-o in Japanese Buddhism and Yan Luo In Chinese Mythology. Some even claim that he also shares the same mythological roots as Abel.

Role

The spirits of the dead are being judged by Yama and his followers (called ‘Yamadutas’) according to their good and bad deeds. They are supposed to either pass through a term of enjoyment in a region midway between the earth and the heaven of the gods, or to undergo their measure of punishment in Naraka (or Jigoku), the nether world, situated somewhere in the southern region. After this time they return to Earth to animate new bodies following the theory of reincarnation.

Yama is also the lord of justice and is sometimes referred to as Dharma, in reference to his unswerving dedication to maintaining order and adherence to harmony. In this capacity, he is normally depicted wearing a Chinese judge’s cap in Japanese art. It is said that he is also one of the wisest of the devas. In the Katha Upanishad, among the most famous Upanishads, Yama is portrayed as a teacher.

Description

In art, Yama is depicted with green or red skin, red clothes, and riding a buffalo. He carries a rope lasso in his left hand to carry the soul back to his abode called ‘Yama-loka’ . In Buddhism, the Wheel of Life mandala is often depicted between the jaws of Yama. Garuda Purana mentions Yama often. His description is in 2.5.147-149:

“There very soon among Death, Time, etc. he sees Yama with red eyes, looking fierce and dark like a heap of collyrium, with fierce jaws and frowning fiercely, chosen as their lord by many ugly, fierce-faced hundreds of diseases, possessing an iron rod in his hand and also a noose. The creature goes either to good or to bad state as directed by him.”

Family

Yama is a Lokapala and an Aditya and one of the Ashta-Dikpalas representing the south. He is the son of Surya (Sun) and twin brother of Yami, or Yamuna, traditionally the first human pair in the Vedas. Yama was also worshiped as a son of Vivasvat and Saranya. His wife is Syamala. Yama is the father of Yudhisthira, the oldest brother of the 5 Pandavas (Karna was born prior to Kunti’s wedlock, so technically Karna is Yudhthira’s older brother) and is said to have incarnated as Vidura by some accounts in the Mahabharata period. Yama reports to Lord Shiva the Destroyer, an aspect of Trimurti (Hinduism’s triune Godhead). Three hymns (10, 14, and 35) in the Rig Veda Book 10 are addressed to him.

Yan Luo Wang (Chinese)

Also known as Bao Yanluo, King Yanlo, Yanluo Wang, Yen-Lo Wang, Yeng-Wang-Yeh Deity of Death and Lord of the Fifth Floor of Hell The God of Death and Ruler of the Fifth Court of Diyu, the Chinese Hell. The Chinese version of Yama, he was originally King of the First Court of Hell, but Heaven accused him of undue leniency.

In Chinese Mythology, Yan Luo is the god of death and the ruler of hell (Diyu). The name Yan Luo is a shortened Chinese transliteration of the Sanskrit term Yama Raja . His personification is always male, and his minions include a judge who holds in his hands a brush and a book listing every soul and the allotted death date for every life.

Bullhead and Horseface, the fearsome guardians of hell, bring the newly dead, one by one, before Yan Luo for judgment.

Meng Po serves in Diyu, the Chinese Kingdom of the dead. This Chinese Goddess appears as an old woman. She prepared a special herbal tea, and this is to give each soul a drink before they leave Diyu. Her important task is to make sure that souls who are ready to be reincarnated should not remember anything about their previous life.