During the early Middle Ages, the Church did not conduct witch trials. The Council of Paderborn in 785 explicitly outlawed the very belief in witches, and Charlemagne later confirmed the law. Among Eastern Christians belief in witchcraft was regarded as deisdemonia—superstition—and by the 9th and 10th centuries in the West, belief in witchcraft had begun to be seen as heresy.

Thomas Aquinas has given credit to many other superstitions that became recognized by the Church as tangible truths. The succubi (underlying or female) and incubi (overlying or male devils), based upon an ancient Babylonian myth about evil spirits and the nocturnal wanderings, were the first incarnations of the witch duly completed by the highest authority in Christendom.

When children are born of the intercourse of devils with human beings, they do not come from the seed of the devil or of the human body, he has assumed, but of seed which he has extracted from another human being.

The same devil, who as a woman, has intercourse with a man can also, in the form of a man, have intercourse with a woman.

Thomas Aquinas gave the Church a finished manual of deviltry, and before the end of the century the Inquisitors in the south of France were condemning women for compacts or cohabitation with the devil.

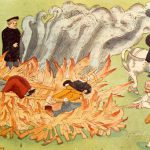

It was in the very year after the death of Thomas Aquinas in 1274 that a woman was for the first time burned as a witch for the reason that she had intercourse with the devil; and it was the Dominican monk and Inquisitor Hugo de Boniols who condemned her. Such trials were still few, when another Pope, John XXII, gave a feverish impulse to the campaign.

Books about witches and devils began to appear. In 1211 one was written by a marshal of the imperial army. In 1220 a Cistercian monk wrote a treatise. In 1233 Pope Gregory IX, as we saw, endorsed the whole story and particularly directed the Inquisitors to seek heretics who were in league with the devil. But it was the founding of the Inquisition and the suppression of open heresy which created the great witch-cult and inaugurated the terrible massacres.

The Church opposed a group it considered heretical, the Albigenses. These deemed heretics were opposed to mainstream Church doctrine, and something was needed to deal with people like them. In 1229 the Dominicans were placed in charge of a tribunal to investigate heresy against the Church; this was essentially the start of the Inquisition which grew to have sweeping powers of life and death.

As the secular rulers and their bishops were considered slow in their struggle against the heresy that was spreading in every country, Gregory IX had, in 1232, taken the “inquiry” (inquisitio) out of the hands of the bishops and given it in charge of the Dominican monks, acting directly under Rome.

This was the founding of the Inquisition as a Papal institution, but it was Innocent III, earlier in the century, who had given it a bloody example to follow. When the heretics of the south of France had laughed at the arguments of his legates, he had stooped to the device of appealing to the greed and lust of all the available military adventurers, and had declared the “crusade” which is known in history as the massacre of the Albigensians.

By the end of the thirteenth century the semi-Manichaean heresy which had spread from Armenia and Bulgaria to France was driven underground by the Inquisition or annihilated by troops. Witchcraft is its next form, as we see clearly in cases which presently occurred in the north of France.