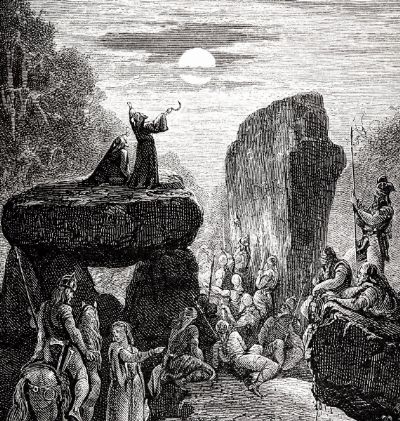

The Celtic festival of Samhain

In the early centuries of the first millennium A.D., before missionaries such as St. Patrick and St. Columcille converted them to Christianity, the Celts practiced an elaborate religion through their priestly caste, the Druids, who were priests, poets, scientists and scholars all at once.

At the end of the nineteenth century , the philologist Sir John Rhys suggested that Halloween had been the ‘Celtic’ New Year. Rhys’s theory was further popularized by the Cambridge scholar, Sir James Frazer. At times the latter did admit that the evidence for it was inconclusive, but at others he threw this caution overboard and employed it to support an idea of his own: that Samhain had been the pagan Celtic feast of the dead, arguing back from a fact, that 1 and 2 November had been dedicated to that purpose by the medieval Christian Church, from which it could be surmised that this was been a Christianization of a preexisting festival. He admitted, by implication, that there was in fact no actual record of such a festival… He suggested that the pope and emperor had, therefore, merely ratified an existing religious practice based upon that of the ancient Celts. The story is, in fact, more complicated.

Christians and Halloween

The Romans observed the holiday of Feralia, intended to give rest and peace to the departed. Participants made sacrifices in honor of the dead, offered up prayers for them, and made oblations to them. The festival was celebrated on February 21, the end of the Roman year

By the mid-fourth century Christians in the Mediterranean world were keeping a feast in honor of all those who had been martyred under the pagan emperors; it is mentioned in the Carmina Nisibena of St Ephraem, [died 373] as being held on 13 May. .

Pope Boniface IV established an anniversary dedicated to the Virgin Mary and the martyrs when he consecrated the Pantheon on May 13, 609 (or 610).

By 800, churches in England and Germany, which were in touch with each other, were celebrating a festival dedicated to all saints upon 1 November instead, perhaps in an effort to supplant the pagan holiday with a Christian observance. The oldest text of Bede’s Martyrology, from the eighth century, does not include it, but the recensions at the end of the century do. Charlemagne’s favourite churchman Alcuin was keeping it by then, as were also his friend Arno, bishop of Salzburg, and a church in Bavaria.

It had not, however, started in Ireland, where the Felire of Oengus and the Martyrology of Tallaght prove that the early medieval churches celebrated the feast of All Saints upon 20 April. The evening before All Saints’ Day became a holy, or hallowed, eve and thus Halloween.

It was officially moved to November 1st from May 13th by Pope Gregory III in the eighth century in order to mark the dedication of the All Saints Chapel in Rome — establishing November 1st as All Saints Day and October 31st as All Hallows’ Eve. Initially this change of date only applied to the diocese of Rome, but was extended to the rest of Western Christianity a century later by Pope Gregory IV in an effort to standardize liturgical worship.

The feast day of All Souls Day, celebrated to commemorate those souls condemned temporarily to Purgatory, was inaugurated by St Odilo, at the time the abbott of the influential monastery at Cluny, on November 2, 998.

He had been told that a hermit dwelling near a cave

heard the voices and howlings of devils, which

complained strongly because that the souls of

them that were dead were taken away from

their hands by alms and by prayers.”

–DE VORAGINE: Golden Legend.

This day became All Souls’, and was set for November 2d.

Phillips states that: “ The Christian church tried to eliminate the Druid celebration by offering All Saint’s Day as a substitute. As Christianity spread over Europe and the British Isles, it attempted to replace the pre- existing pagan cult worship of Apollo, Diana or Ymir, but to no avail. “

While missionaries identified their holy days with those observed by the Celts, they branded the earlier religion’s supernatural deities as evil, and associated them with the devil. As representatives of the rival religion, Druids were considered evil worshipers of devilish or demonic gods and spirits. The Celtic underworld inevitably became identified with the Christian Hell.

The effects of this policy were to diminish but not totally eradicate the beliefs in the traditional gods. Pure Celtic influences lingered longer on the western fringes of Europe, especially in areas that were never brought firmly under Roman control, such as Ireland, Scotland, and the Brittany region of northwestern France. Celtic belief in supernatural creatures persisted, while the church made deliberate attempts to define them as being not merely dangerous, but malicious. Followers of the old religion went into hiding, branded as witches. However, the folk continued to propitiate those spirits (and their masked impersonators) by setting out gifts of food and drink.

By the end of the Middle Ages, the secular (Samhain) and the sacred days had merged in most European countries. The Reformation essentially put an end to the religious holiday among Protestants, although in Britain especially Halloween continued to be celebrated as a secular holiday.

Halloween comes to America

In the United States, the first recorded instance of a Halloween celebration occurred in Anoka, Minn., in 1921

Halloween did not become a holiday in America until the 19th century, where lingering Puritan tradition meant even Christmas was scarcely observed before the 1800s. North American almanacs of the late 18th and early 19th centuries make no mention of Halloween in their lists of holidays.

The transatlantic migration of nearly two million Irish following the Irish Potato Famine (1845–1849) brought the holiday and its customs to America. Scottish emigration from the British Isles, primarily to Canada before 1870 and to the United States thereafter, brought that country’s own version of the holiday to North America. The celebration of Halloween was at first limited in colonial New England because of the rigid Protestant belief systems there. Halloween was much more common in Maryland and the southern colonies.

As the beliefs and customs of different European ethnic groups and the American Indians meshed, a distinctly American version of Halloween began to emerge. The first celebrations included “play parties,” which were public events held to celebrate the harvest. Neighbors would share stories of the dead, tell each other’s fortunes, dance and sing.

When the holiday was observed in 19th-century America, it was generally in three ways. Scottish-American and Irish-American societies held dinners and balls that celebrated their heritages, with perhaps a recitation of Robert Burns’ poem “Hallowe’en” or a telling of Irish legends, much as Columbus Day celebrations were more about Italian-American heritage than Columbus. Home parties would center around children’s activities, such as bobbing for apples and various divination games, particularly about future romance. Colonial Halloween festivities also featured the telling of ghost stories, pranks and mischief-making of all kinds.

Commercial exploitation of Halloween in America did not begin until the 20th century. The earliest were perhaps Halloween postcards, which were most popular between 1905 and 1915, and featured hundreds of different designs. Dennison Manufacturing Company, which published its first Halloween catalog in 1909, and the Beistle Company were pioneers in commercially made Halloween decorations, particularly die-cut paper items. German manufacturers specialized in Halloween figurines that were exported to America in the period between the two world wars.

There is little primary documentation of masking or costuming on Halloween in America, or elsewhere, before 1900. Mass-produced Halloween costumes did not appear in stores until the 1950s, when trick-or-treating became a fixture of the holiday, although commercially made masks were available earlier.