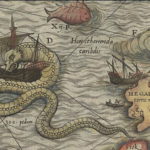

Tales of giant squid have been common among mariners since ancient times, and may have led to the Norwegian legend of the kraken, a tentacled sea monster as large as an island capable of engulfing and sinking any ship.

Japetus Steenstrup, the describer of Architeuthis, suggested a giant squid was the species described as a sea monk to the Danish king Christian III c.1550. The Lusca of the Caribbean and Scylla in Greek mythology may also derive from giant squid sightings. Eyewitness accounts of other sea monsters like the sea serpent are also thought to be mistaken interpretations of giant squid.

Pliny the Elder, living in the first century A.D., also described a gigantic squid in his Natural History, with the head “as big as a cask”, arms 30 feet (9.1 m) long, and carcass weighing 700 pounds (320 kg).

There is a recorded incident of a kraken becoming trapped in the cleft of a rock when it swam to close to the Norwegian shore in 1680. The putrid stench of its rotting body supposedly remained for months.

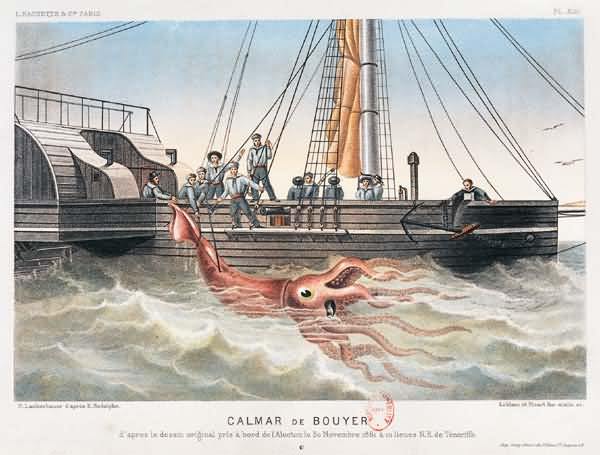

Steenstrup wrote a number of papers on giant squid in the 1850s. He first used the term “Architeuthus” (this was the spelling he chose) in a paper in 1857. A portion of a giant squid was secured by the French gunboat Alecton in 1861 leading to wider recognition of the genus in the scientific community.

From 1870 to 1880, many squid were stranded on the shores of Newfoundland. For example, a specimen washed ashore in Thimble Tickle Bay, Newfoundland on November 2, 1878; its mantle was reported to be 6.1 metres (20 ft) long, with one tentacle 10.7 metres (35 ft) long, and it was estimated as weighing 2.2 tonnes. In 1873, a squid “attacked” a minister and a young boy in a dory in Bell Island, Newfoundland. Many strandings also occurred in New Zealand during the late 19th century.

In 1875 the barque Pauline spotted a sperm whale with a snake-like creature wrapped around it’s mid-section. The crew reported this sea serpent eventually dragged the whale down to its death.

More likely the “snake” was the arm of a large squid in battle with the whale. Many old mariners’ tales include crewmembers being whisked off deck by giant tentacles armed with plate sized suction cups. There are also some instances where one of the giant arms are hacked off or found washed up on shore.

Clyde Ropper from the Washington Smithsonian Institute has been looking from the “big one” for the last 37 years. In 1997 and 1999, he set up two expeditions to explore the depths of the Kaikoura canyon in New Zealand where the hoki, favorite dish of the beast, abounds.

In 1997, the crew used a special prop call Deep Rover to film as deep as 1000 m. Clyde has even attached a camera on a whale, hoping the monster would attack it.

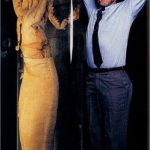

In 2004, another giant squid, later named “Archie”, was caught off the coast of the Falkland Islands by a trawler. It was 8.62 metres (28.3 ft) long and was sent to the Natural History Museum in London to be studied and preserved. It was put on display on March 1, 2006 at the Darwin Centre.

The first photographs of a live giant squid in its natural habitat were taken on September 30, 2004, by Tsunemi Kubodera (National Science Museum of Japan) and Kyoichi Mori (Ogasawara Whale Watching Association). Their teams had worked together for nearly two years to accomplish this. The researchers were able to locate the likely general location of giant squid by closely tailing the movements of sperm whales. They used a five-ton fishing boat and only two crew members.

The images were created on their third trip to a known sperm whale hunting ground 970 kilometres (600 mi) south of Tokyo, where they had dropped a 900-metre (3,000 ft) line baited with squid and shrimp. The line also held a camera and a flash. After over 20 tries that day, an 8-metre (26 ft) giant squid attacked the lure and snagged its tentacle. The camera took over 500 photos before the squid managed to break free after four hours. The squid’s 5.5-metre (18 ft) tentacle remained attached to the lure. Later DNA tests confirmed the animal as a giant squid.