In many parts of Britain and Ireland Halloween used to be known as ‘Mischief Night’, which meant that people were free to go around the village playing pranks and getting up to any kind of mischief without fear of being punished.

Irisleabhar na Gaedhilge, ii, 370, states that in parts of Count Waterford: ‘Hallow E’en is called oidhche na h-aimléise, “The night of mischief or con”. It was a custom which survives still in places — for the “boys” to assemble in gangs, and, headed by a few horn-blowers who were always selected for their strength of lungs, to visit all the farmers’ houses in the district and levy a sort of blackmail, good humorously asked for, and as cheerfully given.

They afterward met at some point of rendezvous, and in merry revelry celebrated the festival of Samhain in their own way. When the distant winding of the horns was heard, the bean a’ tigh [woman of the house] got prepared for their reception, and also for the money or builín (white bread) to be handed to them through the half-opened door.

There was always a race amongst them to get possession of the latch. Whoever heard the wild scurry of their rush through a farm-yard to the kitchen-door — will not question the propriety of the word aimiléis [mischief] applied to their proceedings. The leader of the band chaunted a sort of recitative in Gaelic, intoning it with a strong nasal twang to conceal his identity, in which the good-wife was called upon to do honour to Samhain…”

In some parts of Yorkshire, Mischief Night falls on the 4 November. Children do tricks on adults which range from the minor to more serious such as taking doors off their hinges on this night. The doors were also often thrown into ponds, or taken a long way away. In recent years these tricks have, in some cases, turned into severe acts of vandalism and criminal damage including streetfires and destruction of private property.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, young people in America also observed Halloween by perpetrating minor acts of vandalism, such as overturning sheds or breaking windows. In Detroit, Michigan, Mischief Night—known there as Devil’s Night—provided the occasion for waves of arson that sometimes destroyed whole city blocks during the 1970s and 1980s.

As Stuart Schneider writes in ‘Halloween in America’ (1995), vandalism that had been limited to tipping outhouses; removing gates, soaping windows and switching shop signs, by the 1920’s had become nasty — with real destruction of property and cruelty to animals and people.

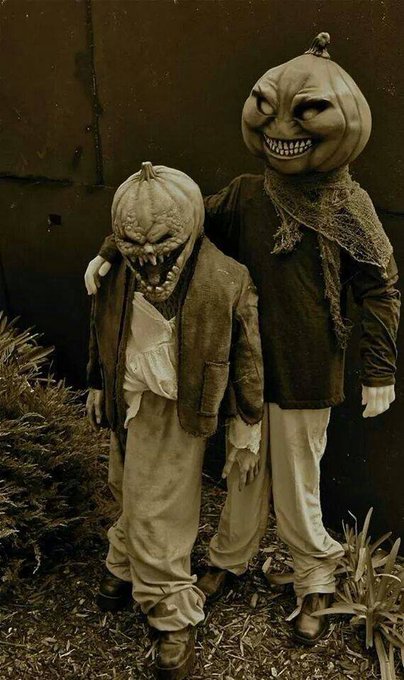

Schneider writes that neighborhood committees and local city clubs such as the Boy Scouts then mobilized to organize safe and fun alternatives to vandalism. School posters of the time call for a “Sane Halloween.” Good children were encouraged to go door to door and receive treats from homes and shop owners, thereby keeping troublemakers away.

In the village of Hiawatha, Kansas, the morning after Halloween in 1912, a woman named Elizabeth Krebs grew tired of having her garden – and entire town – vandalized once a year by marauding children wearing masks and, initially using her own resources, organized a party in 1913 for the young people where, she hoped, she would tire them out enough that they would have no energy for destruction.

She underestimated their determination, however, and the community was vandalized as usual. In 1914, she involved the entire town, brought in a band, held a costume contest, and put on a parade – and her plan worked. People of all ages enjoyed a festive, rather than disruptive, Halloween. News of her success traveled outside of Kansas to other towns and cities which adopted the same course and established Halloween parties which included costume contests, parades, music, food, dancing, and sweet treats accompanied by frightening decorations of ghosts and goblins.

By the 1930’s, these “beggar’s nights” were enormously popular and being practiced nationwide, with the “trick or treat” greeting widespread from the late 1930’s