Nineteenth century Gothic horror stories drew on previous folklore and legend to present the theme of the werewolf in a new fictional form.

An early example is Hugues, the Wer-Wolf by Sutherland Menzies published in 1838. In another, Wagner the Wehr-Wolf (1847) by G. W. M. Reynolds, we find the classic subject of a man cursed to be transformed into a werewolf at the time of the full moon: representing the split personality and evil, bloodthirsty, dark side of humanity itself.

Other werewolf stories of this period include The Wolf-Leader (1857) by Alexandre Dumas and Hugues-le-Loup (1869) by Erckmann-Chatrian.

A later Gothic story, Robert Lewis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), has an implicit werewolf subtext, according to Colin Wilson. This has been made explicit in some recent adaptations of this story, such as the BBC TV series Jekyll (2007). Stevenson’s Olalla (1887) offers more explicit werewolf content, but, like Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, this aspect remains subordinate to the story’s larger themes.

A rapacious female werewolf who appears in the guise of a seductive femme-fatale before transforming into lupine form to devour her hapless male victims is the protagonist of Clemence Houseman’s acclaimed The Were-wolf published in 1896.

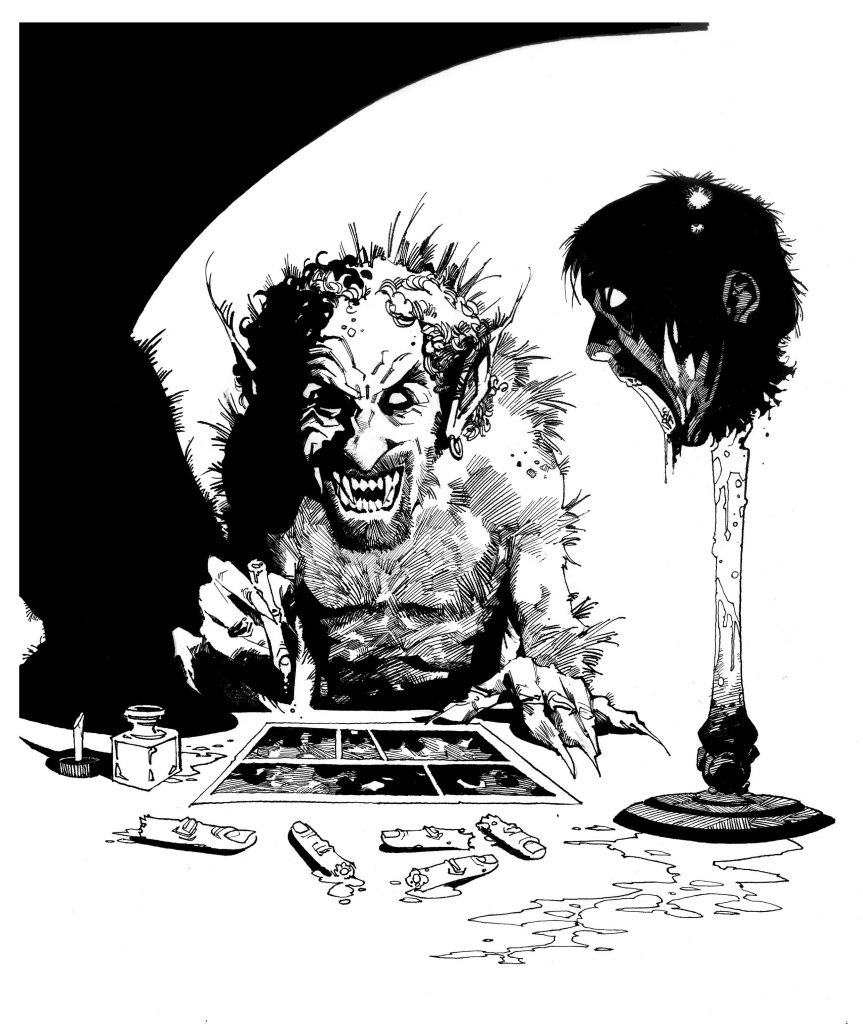

Wagner, the Wehr-wolf

This 1857 melodrama by George W.M. Reynolds features a Faustian pact between a German peasant and the devil as the origin of the transformation, and an exchange of wolfishness every seven years for wealth and immortality. So Wagner is nothing more than a beast really and never was an interesting character in his own right as was Varney the Vampire. But the enormous penny-dreadful text is online in its entirety, and I’d be glad to read someone’s scholarly review.

The Other Side

Eric Stenbock’s 1893 story focuses on young loner Gabriel, living amid superstitious, hateful, small-minded townsfolk. From the woods on the opposite side of a brook one can hear wolves howling, and rumors of werewolves thrive.

Interestingly, the story distinguishes between “the were-wolves and the wolf-men and the men-wolves” (270). (Wolf-men have wolf-heads; men-wolves have wolf-bodies — pretty creepy.)

A blue flower attracts Gabriel to “the other side” and he witnesses a procession (not marauding beasts). Gabriel crosses back. Eventually wolf-woman Lilith seems to replicate Gabriel’s own domestic surroundings, minus religious icons, in a through-the-looking-glass episode. Gabriel later sees his wolf-body reflection in the brook (277).

Another glimpse of “this side” shows the brutality — “‘Gabriel is skulking and hiding himself, he’s afraid to join the wolf hunt; why, he wouldn’t even kill a cat,’ for their one notion of excellence was slaughter” (278) — and the ignorance — “Their knowledge of other localities being so limited, that it did not even occur to them to suppose he might be living elsewhere than in the village” (278).

In the end, religious ritualistic magic destroys the other side. “The ‘other side’ is harmless now — charred ashes only; but none dares to cross but Gabriel alone — for once a year for nine days a strange madness comes over him” (280).

Of course we’re supposed to assume initially that safety, civilization, propriety, and piety are on “our side.” But this side consists of brutality, murderousness, ignorance, and religious paraphernalia. What is horrible about the other side? Their alternative religion amounts to a procession, but they do nothing — no ravening beasts from hell. So who are the monsters?