An ossuary is a chest, building, well or site made to serve as the final resting place of human skeletal remains.

A body is placed in a temporary grave, and then sometime later the bones are removed, cleaned and placed in the ossuary – the final resting place. In many instances ossuaries were created as a solution to the lack of space in local cemeteries. Others, however, came about when human remains were recovered during the excavation of cemeteries – whether known or forgotten. The greatly reduced space taken up by an ossuary means that it is possible to store the remains of many more people in a single tomb than in coffins.

History

Ossuaries have a long history. The megalithic chambered tombs of the Neolithic and Bronze Age are in all likelihood prehistoric antecedents of the more recent traditions.

In Persia

In Persia the Zoroastrians used a deep well for this function from the earliest times (c. 3,000 years ago) and called it astudan (literally, “the place for the bones”). There are many rituals and regulations in the Zoroastrian faith concerning the astudans. The Iranian Aryans in the region of central-Asia called an ossuary tanbar and used them from very ancient times.

In Judaism

In Judaism in the first-century B.C. to about A.D. 70, as space for burial tombs was scarce, it was the Jewish burial custom to place their dead in a cave for a year, and once the body had become skeletonised, the bones were collected and placed in a chest that served as the ossuary. It is also referred to as a bone box. Some ossuaries were found to be intricately carved, some with feet. The ossuary of the high priest Caiaphas has been discovered from these times.

The James Ossuary

In 2002, an ossuary allegedly belonging to James the Just was brought to the public’s attention by Oded Golan and Andre Lemaire. If authentic, the 2,000 year old ossuary which bore the inscription, “James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus.” would have been the first archaeological proof that Jesus existed, which until then, the only references to the three men were found in manuscripts. It was however found that though the box was correctly dated, the inscription it bore was a forgery. There is some controversy as to how the box was dated; however, Oded Golan, who was believed to have created the inscription was later indicted for fraud.

Europe of Christianity

Ossuaries are found throughout Europe, having been a common practice for both Catholic and Eastern Orthodox communities. There are chapels and crypts in churches and monasteries that house the bones of thousands of individuals. Caves, catacombs and underground tunnels also make for ideal ossuaries. People were interred as and when when they died, whereas some ossuaries are a kid of ‘mass grave’, holding the bones of thousands of individuals who died a a result of anything from plagues to wars

Many examples of ossuaries are found within Europe, including the Santa Maria della Concezione dei Cappuccini in Rome, Italy; the Martyrs of Otranto in south Italy; the Fontanelle cemetery and Purgatorio ad Arco in Naples, Italy; the San Bernardino alle Ossa in Milan, Italy; the Brno Ossuary and the Sedlec Ossuary in the Czech Republic; the Czermna Skull Chapel in Poland; and the Capela dos Ossos (“Chapel of Bones”) in Évora, Portugal. A more recent example is the Douaumont ossuary in France, which contains the remains of more than 130,000 French and German soldiers that fell at the Battle of Verdun during World War I. The Catacombs of Paris represents another famous ossuary.

Largest most famous ossuaries and necropolis

The Sedlec Ossuary, Sedlec, Czech Republic

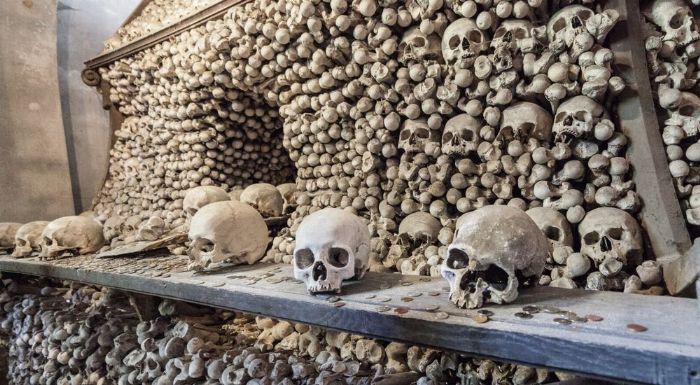

The Sedlec Ossuary is a Roman Catholic chapel, located beneath the Cemetery Church of All Saints, part of the former Sedlec Abbey in Sedlec, a suburb of Kutná Hora in the Czech Republic. The ossuary is estimated to contain the skeletons of between 40,000 and 70,000 people, whose bones have, in many cases, been artistically arranged to form decorations and furnishings for the chapel. The ossuary is among the most visited tourist attractions of the Czech Republic, attracting over 200,000 visitors annually.

Santa Maria della Concezione, Rome, Italy

The crypt is located just under the church. Cardinal Antonio Barberini, who was a member of the Capuchin order, in 1631 ordered the remains of thousands of Capuchin friars exhumed and transferred from the friary Via dei Lucchesi to the crypt. Here the Capuchins would come to pray and reflect each evening before retiring for the night. The crypt, or ossuary, now contains the remains of 4,000 friars buried between 1500 and 1870, during which time the Roman Catholic Church permitted burial in and under churches.

Brno Ossuary, Brno, Czech Republic

Brno Ossuary is an underground ossuary in Brno, Czech Republic. It was rediscovered in 2001 in the historical centre of the city, partially under the Church of St. James. It is estimated that the ossuary holds the remains of over 50 000 people which makes it the second-largest ossuary in Europe, after the Catacombs of Paris. The ossuary was founded in the 17th century, and was expanded in the 18th century. A Czech anthropologist, Jindrich Matiegka stacked the bones into orderly piles and meaningful patterns. The largest pile can be seen directly in front of the entrance and is 15 feet square and over six feet high, and is believed to contain roughly 10,000 skeletons.

The Capela dos Ossos, Évora, Portugal

The Capela dos Ossos (English: Chapel of Bones) is one of the best-known monuments in Évora, Portugal. It is a small interior chapel located next to the entrance of the Church of St. Francis. The Chapel gets its name because the interior walls are covered and decorated with human skulls and bones.

The Capela dos Ossos was built by Franciscan monks. An estimated 5,000 corpses were exhumed to decorate the walls of the chapel. The bones, which came from ordinary people who were buried in Évora’s medieval cemeteries, were arranged by the Franciscans in a variety of patterns.

The Catacombs of Paris, France

Beneath the streets of most parts of Paris (intramuros) is an enormous network of underground tunnels. The tunnels were dug since the Roman era, and it is from here that much of the stone used to build Paris comes from. Although the ossuary comprises only a small section of the underground mines of Paris, Parisians currently often refer to the entire tunnel network as the catacombs.

The Catacombs of Paris consist of nearly 186 miles of tunnels, of which about only three acres are packed with re-interred bones. The ossuaries, which hold the remains of more than six million people in a small part of a tunnel network built to consolidate Paris’ ancient stone quarries. Extending south from the Barrière d’Enfer (“Gate of Hell”) former city gate, this ossuary was created as part of the effort to eliminate the city’s overflowing cemeteries. Preparation work began shortly after a 1774 series of basement wall collapses around the Holy Innocents’ Cemetery added a sense of urgency to the cemetery-eliminating measure, and from 1786, nightly processions of covered wagons transferred remains from most of Paris’ cemeteries to a mine shaft opened near the Rue de la Tombe-Issoire.

Wamba Ossuary, Wamba, Spain

The Wamba Ossuary is one of the largest ossuaries in Spain, it lies deep within the vaults of Santa Maria Church in Wamba, and it displays the skeletons of thousands of monks and villagers alike. The compilation of bones is so dense that you could almost overlook the 3,000 skulls staring out at you from amongst the rest of the remains.

The bones were placed at Santa Maria Church between the 12th and 18th centuries. In 1931, the site finally became a protected historical location.

St. Bartholomew’s Church, Lower Silesia, Poland.

The Skull Chapel (Polish: Kaplica Czaszek) or St. Bartholomew’s Church, is an ossuary chapel located in the Czermna district of Kudowa, a town in Kłodzko County, Lower Silesia, Poland. Built in last quarter of the 18th century on the border of the then Prussian County of Glatz, the temple serves as a mass grave with over 3,000 people, decorating the ceiling and walls, and arranged in various patterns — mostly in a repeating crossed bones Jolly Roger-style — with another 21,000 skeletons stuffed in the church crypt below. Collected by Czech priest Vaclav Tomasek and J. Langer, the local grave digger, it took the pair some 18 years, from 1776 to 1794, to collect, clean and arrange the as many as 24,000 human skeletons that pack the church.

Monastery of San Francisco, Lima, Peru

The catacombs beneath the Monastery of San Francisco in Lima, Peru, also contains an ossuary.[9]

Basilica and Convent of San Francisco of Lima, also known as “San Francisco el Grande” or “San Francisco de Jesús”, is located in the Historic Center of Lima, Peru.

The building includes catacombs, which were the old cemetery in colonial times. It operated as such until 1810 and it is estimated that at that time it must have housed up to 70,000 people. Today the different rooms contain a good number of bones classified by type and arranged on some occasions in a rather artistic fashion, such as those in the mass grave.

The Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo, Palermo, Sicily, southern Italy.

The catacombs are said to hold 8,000 bodies but the number is probably closer to 2,000, some of them quite notable. There are members of the Sicilian aristocracy, lawyers, doctors, artists and even the son of a Tunisian king inside, their preserved bodies dressed in clothes they wore in life resting for eternity below the streets of Palermo.

Palermo’s Capuchin monastery outgrew its original cemetery in the 16th century and monks began to excavate crypts below it. In 1599 they mummified one of their number, the recently-deceased brother Silvestro of Gubbio, and placed him in the catacombs.

Bodies were dehydrated on racks of ceramic pipes in the catacombs and sometimes later washed with vinegar. Some bodies were embalmed and others were enclosed in sealed glass cabinets. Friars were preserved with their everyday clothing and sometimes with ropes they had worn in penance.

Initially the catacombs were intended only for deceased friars. However, in later centuries it became a status symbol to be entombed in the Capuchin catacombs. In their wills, local luminaries would ask to be preserved in certain clothes, or even have their clothes changed at regular intervals. Priests wore their clerical vestments, while others were clothed according to contemporary fashion. Relatives would visit to pray for the deceased and to maintain the body in presentable condition.

The warren of rooms are divided into separate sections. Priests are dressed in their clerical vestments and military and public officials still wear their dress uniforms. There are dedicated rooms for virgins, women, men, children and infants. Some bodies are embalmed and displayed in glass caskets while others are hung in a standing position from the walls. Many of the bodies are now protected by wire cages because people were taking bones as macabre souvenirs.

One of the most famous and heartbreaking residents of the catacombs is Rosalia Lombardo. Rosalia was just two years old when she died tragically of pneumonia. She appears dressed in a party dress, as if she is just sleeping in a glass coffin, her body perfectly preserved with a slight purple cast. The embalming technique was a mystery until Italian biological anthropologist, Dario Piombino-Mascali, who works with the Institute for Mummies and the famous Iceman in Bolzano, tracked down living relatives of the embalmer. Alfredo Salafia was a Sicilian taxidermist and embalmer who died in 1933. His handwritten notes outline a chemical formula of formalin, zinc salts, alcohol, salicylic acid and glycerin that account for the incredible condition of the sweet lost Rosalia.

Phnom Penh Memorial Stupa, Cambodia

The Khmer Rouge killed 1.7 people between 1975 and 1979, following the Cambodian Civil War. Many of those people were buried in unceremonious mass graves in what’s known today as the Killing Fields. At Phnom Penh Memorial Stupa in Cambodia, the remains of an estimated 10,000 people are arranged in multiple layers within a Buddhist-style Stupa.

Douaumont Ossuary, Verdun, France

Situated on what was the battlefield of the World War One Battle of Verdun and next to the largest French military cemetery relating to the first World War, the ossuary holds the remains of both French and German soldiers who fought in that horrific battle.

The bones from at least 130,000 unidentified soldiers have been placed in specially designed alcoves. Their names have been inscribed on the walls and vaulted ceiling of the ossuary. The adjacent cemetery has the identified remains of 16,142 French men. L’ossuaire de Douaumont was inaugurated by French President Albert Lebrun on 7 August in 1932.