The púca (plural púcaí) is a shapeshifter of Norse and Celtic folklore. Considered to be bringers both of good and bad fortune, púcaí could help or scare members of human farming communities.

Other names for Pooka include púca, phouka, phooka, phooca, puca, plica, phuca, pwwka, pookha or púka.

Form

According to legend, the púca is a deft shapeshifter, capable of assuming a variety of terrifying or pleasing forms. It can take a human form, but will often have animal features, such as ears or a tail. As an animal, the púca will most commonly appear as a horse but it can turn into a cat, rabbit, raven, fox, wolf, goat, goblin, or dog. No matter what shape the púca takes, its fur is almost always dark.

In some parts of County Down, the púca is manifested as a short, disfigured goblin who demands a share of the harvest; in County Laois, it appears as a monstrous bogeyman, while in Waterford and Wexford the púca appears as an eagle with a huge wingspan and in Roscommon as a black goat.

Pookas often take human form to trick people, chat with them, give them advice, or even give forecasts for the upcoming year. They usually appear and vanish from and into the air, leaving no trace of their passage.

Its favorite shape is that of a sleek black horse with a flowing mane and luminescent golden eyes. In one of the most well-known Irish folktales featuring the púca, “The Piper and the Pooka,” the spirit appears as a bipedal goblin with horns on his head. Later, he transforms into a horse and carries the eponymous piper to a feast at the house of the banshees.

The púca appears as a horse again in the story “Mac-na-Michomhairle,” as relayed by Douglas Hyde to Yeats:

[O]ut of a certain hill in Leinster, there used to emerge as far as his middle, a plump, sleek, terrible steed, and speak in human voice to each person about November-day, and he was accustomed to give intelligent and proper answers to such as consulted him concerning all that would befall them until the November of next year. And the people used to leave gifts and presents at the hill until the coming of Patrick and the holy clergy.

Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry (1888)

Etymology

[The púca] occurs in later legend and seems to have no basis in myth, probably being an import from the Norse púki, an imp, from where it also went into Welsh pwca and into English as puck.”

Ellis: A Dictionary of Irish Mythology (1987)

In Welsh mythology it is named the pwca and in Cornish the Bucca. In the Channel Islands, the pouque were said to be fairies who lived near ancient stones; in Norman French of the Islands (e.g. Jèrriais), a cromlech, or prehistoric tomb, is referred to as a pouquelée or pouquelay(e); poulpiquet and polpegan are corresponding terms in Brittany.

The most famous iteration of this folkloric figure, of course, is the “shrewd and knavish” Puck (a.k.a. Robin Goodfellow) from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Pooka and Halloween

The púca is associated with Samhain, when the last of the crops are brought in. Anything remaining in the fields is considered “puka”, or fairy-blasted, and hence inedible. The puca was known to either defecate or spit on the berries that have been killed by a frosty overnight rendering them inedible and unsafe thenceforth. When the harvest is being brought in the reaper must leave a few stalks behind, called the Pookas share. Nonetheless, 1 November is the púca’s day, and the one day of the year when it can be expected to behave civilly.

Douglas Hyde, the folklore specialist, described the Pooka as a “plimr, sleek, terrible steed” that walked down from one of Leinster’s hills and talked to the people in the 1st of November. According to Hyde, the Pooka provided them with “intelligent and proper answers to those who consulted it concerning all that would befall them until November the next year. And the people used to leave gifts and presents at the hill.”

Place

Pooka’s can be found in any rural location. They like open mountainous areas so that they can run free while in horse form.

Irish folk tales tell us that the púca makes his home “[o]n solitary mountains and among old ruins,” (source: Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, 1888).

In the Wicklow Mountains, Liffey river has created a waterfall which people call “Poula Phouka” which means “the Pooka’s hole.” Also in County Fermanagh, the top of Binlaughlin Mountain is known for the “peak of the sneaking horse.” In Belcoo, County Fermanagh, St. Patrick Wells were said to be called “Pooka Pools” thousands of years ago, but religious Christians changed their name. Many small mountainous lakes and springs in Ireland are still called ‘Pooka Pools’ or ‘Pollaphuca’, which means Pooka or Demon hole.

Tricks

If a human is enticed onto a púca’s back, it has been known to give them a wild ride; however, unlike a kelpie, which will take its rider and dive into the nearest stream or lake to drown and devour them, the púca will do its rider no real harm. This usually happened when the rider in question is drunk, and is making his way home from a night at the pub.

According to some folklorists, the only man ever to ride the púca was Brian Boru, High King of Ireland, by using a special bridle incorporating three hairs of the púca’s tail. Stories say that King Brian also forced Pookas to agree on never hurting Christians or messing with their properties and never assaulting an Irishman except for those with wicked intentions and drunk Irishmen.

The púca has the power of human speech, and has been known to give advice and lead people away from harm. Though the púca enjoys confusing and often terrifying humans, it is considered to be benevolent. In some tales, Pooka behaves like a protective entity and intervenes before a terrible accident or before the person is about to happen upon a malevolent fairy or spirit. In several of the regional variants of the stories where the púca is acting as a guardian, Pooka identifies itself to the bewildered human whereas most malevolent fairies and demons would conceal their names.

Protection

While púca stories can be found across northern Europe, Irish tales specify a protective measure for encountering a púca. It is said that the rider may be able to take control of the púca by wearing sharp spurs, using those to prevent being taken or to steer the creature if already on its back.

A translation of an Irish púca story, “An Buachaill Bó agus an Púca”, told by storyteller Seán Ó Cróinín, describes this method of control of the púca as done by a young boy who had been the creature’s target once before:

… the farmer asked the lad what had kept him out so late. The lad told him.

“I have spurs,” said the farmer. “Put them on you tonight and if he brings you give him the spurs!” And this the lad did. The thing threw him from its back and the lad got back early enough. Within a week the (pooka) was before him again after housing the cows.

“Come to me,” said the lad, “so I can get up on your back.”

“Have you the sharp things on?” said the animal.

“Certainly,” said the lad.

“Oh I won’t go near you, then,” he said.

See also Apotropaic objects

Pooka in modern culture

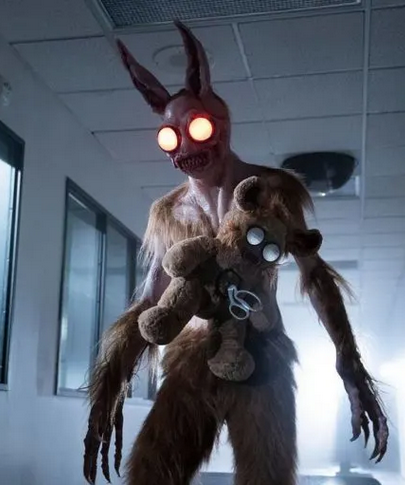

In the movie Harvey (1950) with James Steward, Pooka is a six-foot white rabbit that becomes a best friend with a man and starts playing tricky games with people around him. In Donnie Darko (2001) it is Frank, a mysterious figure in a rabbit costume who informs Donnie, a troubled teenager, that the world will end in just over 28 days then manipulates him to commit several crimes. Many other representations including the series Merry Gentry, the anime show Sword Art Online, and the digital game Cabals: Magic & Battle Cards depict Pookas as crazy or evil creatures.