The woman is variously a wood-wife (Germany or Switzerland), a mermaid (W. Jutland), one of the “hulder-folk” (Sweden), or an elf (Denmark). The hunter chasing the woman always appears as a solitary figure. The theme of this supernatural hunt seems to have little connection with the damned lord leading a group of hunters. It is probably an independent tradition that derived from the killing of the giant women but the mighty god Thorr.

In some German tales, she leads a train of souls which importantly, often includes young children (Orla-gau). She frequently gives gifts to children (another aspect of Teutonic Yule tradition which must have contributed to the Father Christmas character), but she steals the children too, embodying the same contrast of benign and malign qualities as the Pied Piper. She also acts as an enforcer of female social norms: she punishes women who have not finished their spinning by the appointed night or who spin on the wrong day.

The Wild Hunt was often mentioned in the witch trials of the Middle Ages, and it was later confused with the departure to the Sabbath. In such tales, the Huntress is seen both as unfettered female sexuality, but also as a child-eater and vampire, bringing her into a connection with the Goddess-figure of Lilith.

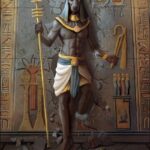

In Southern Germany the Hunt leader was usually called Perchta, Berhta or Berta, and called “the bright one”, which may explain why Latin authors called her Diana.

In central Germany the Goddess was associated with agriculture rather than the Hunt as such, and called Holt, Holle or Hulda. Around 1100 the Huntress began to be called Pharaildis, which Burton, in his book “Witchcraft in the Middle Ages” suggests was a confusion between Frau Hilde and St Pharaildis, who actually had nothing to do with fertility.

In Sweden and Northern Germany, she is Frien, Freki, Frik or Freja.

Particularly in Austria and Scandinavia, the Yule-time female figure who can either be the kindly gift-giver or the fearsome demon is St. Lucia, who also is associated with animal-masking.

In Austria, she is Spillalutsche, “Spindle-Lucia,” who punishes children and spinners with red-hot bobbins.

In Schleswig-Holstein the Holda-figure is shown with a cow skin and horns, and a cow’s head or foot marks Lucy Day on some of the Scandinavian rune-stocks (Liungman, Waldemar, Traditionswanderungen Euphrat-Rhein, part II. FF Communications 119, 1938, pp. 654-55).

On the Elbe, a feminine leader of the Wild Hunt appears, called Fru Wode or Fru Gode; the Wild Hunt is also said to be led by a Frau Gauden in Mecklenburg (Lisch, Mecklenburger jahrbuch, 8, 202-5).

In France the fertility aspect of this Goddess was more evident, with the names Abundia and Satia being recorded

In Italy she was known as Befana, Befania or Epiphania, the latter name probably coming from the Christian festival of Epiphany, where ancient New Year’s rites were still celebrated.

A variant of the Wild Hunt in which the hunter chases after a supernatural female is known from Sweden to the Tyrollean Alps, and first appears in the Germanic countries as a part of Middle High German heroic literature, in the Ecken-Lied. The basic theme is characterized by this Swedish tale.

“My father and my grandfather were out hunting in Solerud Forest one day. That evening they heard a strange barking; there was one hound barking very shrilly, and there were also two with a deeper cry…. All at once, a woman came running by with her hair streaming out behind her. Next came the hound that barked so shrill, and then the two others. Shortly after, along came a man with red hair and beard. He had a gun with him. He just went straight along. Father said this was Oden’s hunt.”

(Simpson, Scandinavian Folktales, p. 226. Collected in 1944 from an informant born in 1860).