In 1823 the novel’s first stage adaptation, Presumption; Or, The Fate of Frankenstein by Richard Brinksley Peake premiered. The creature, his face yellow and green, his limbs blue, was speechless; the novel’s complex moral explorations were reduced to a single moral: Frankenstein got punished for treading in God’s domain. Exciting scenes with the Monster alternated with sentimental set pieces among the other characters, several of whom kept breaking into song. Frankenstein was given a comical servant, named Fritz, who wasn’t privy to his master’s experiments.

Through the 19th century there were several more Frankenstein stage melodramas in England and the U.S., Paris and Vienna, as well as Frankenstein parodies, including Frankenstich, Frank-in-Steam, and The Model Man. Cooke, and later O. Smith, became closely identified with the Monster, playing him in multiple productions. The Monster and vampires began to appear together in plays. As early as the 1820s, the name “Frankenstein” started to be used interchangeably for the Monster and the Monster’s maker.

In 1910 the Edison Studios released a 14-minute Frankenstein, starring Charles Ogle as a patchwork monster, hunchbacked, hairy, clawed. It took shape in a cauldron of blazing chemicals, an effect achieved by setting fire to a dummy, then running the results backward. Long thought a lost film, it has recently turned up. In the second official adaptation, Life Without Soul (1915), Percy Darrell Standing played the “Brute Man” without monster makeup. It remains a lost film, as does Italy’s The Monster of Frankestein (1920).

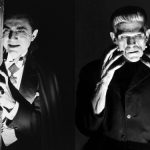

In 1931, Universal acquired the rights to a companion piece, Peggy Webling’s 1927 British play, Frankenstein: An Experiment in the Macabre, adapted for the American stage in 1931 by Hamilton Deane. After the success of Dracula with director Tod Browning and featuring new star Bela Lugosi, Carl Laemmle Jr., Universal Studios production chief, offered Whale his choice of some 30 Universal properties. Whale picked Frankenstein.

Casting the Monster was a challenge. In the developing screenplay he would remain mute, but he would be a complex person. They needed an actor of subtlety and range. Whale’s romantic partner, David Lewis (a film producer), suggested that Whale test an obscure but experienced character actor named William Henry Pratt, who went by the stage name Boris Karloff.

On meeting the 43-year-old actor, Whale was fascinated by his face and “penetrating personality.” The key to Whale and Karloff’s shared vision is that the Monster is a oversized newborn child, his lurching, loose-armed walk that of a toddler struggling to keep his balance.

Frankenstein was a run-away success, bigger than Dracula. Karloff became a superstar, and horror films grew from an occasional oddity to a full-fledged film genre, particularly at Universal. As the studio released such other horror/gothic classics as The Mummy (1932), The Black Cat (1934), and Whale’s The Old Dark House (1932) and The Invisible Man, demand naturally grew for a sequel to their biggest shocker.

The Laemmle family lost control of Universal in 1936 and horror went into eclipse, but the successful re-release of the 1931 Dracula and Frankenstein led the new management to launch Son of Frankenstein (1939). Director Rowland V. Lee lacked Whale’s genius but he was a solid storyteller, and Son has several virtues, including the impressionistic look of Castle Frankenstein, Lugosi’s performance as the sly, broken-necked Ygor, and Lionel Atwill’s memorable performance as wooden-armed Inspector Krogh. Basil Rathbone as Dr. Wolf von Frankenstein is also memorable but the original “son of Frankenstein,” Karloff’s Monster, appears only in three scenes. Sensing a downhill trend for the character, Karloff declined the part in subsequent Universal films.

Ghost of Frankenstein (1942), too, has it virtues, including a reprise of Lugosi as Ygor and Sir Cedrick Hardwicke’s dignified performance as Wolf’s brother, Dr. Ludwig Frankenstein. But Lon Chaney, Jr., who brought so much sincere emotion to Lawrence (Wolf Man) Talbot, makes a curiously flat Frankenstein’s Monster.

At the end of Ghost, Ygor tricks Dr. Frankenstein into putting his (Ygor’s) brain into the Monster’s head. But the fiendish Ygor Monster’s reign of terror is cut short when a mismatched blood type makes him blind. In Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943) Universal logically cast Lugosi as the Monster since Ygor’s brain was now doing the driving. As originally shot, the film showed the Monster as blind and speaking in Ygor’s voice !

House of Frankenstein (1944), House of Dracula (1945), and Abbott and Costello Meets Frankenstein (1948) each have their charms, but those charms are supplied by the Wolf Man (Chaney), Count Dracula (John Carradine and Lugosi), Bud and Lou, and assorted mad scientists and (mostly hunchbacked) assistants. The Monster (played by Glenn Strange) has become, simply, the boogeyman, comatose until the final reel, when he’s revived by electricity, only to get killed again.

After the WWII and the first atomic bomb test, sci-fi horror came to the front, featuring either giant monsters created by radioactivity or sinister space aliens.

In 1957 Universal sold its classic horror films to television as a package entitled Shock Theater. Monster Culture was born, and a new burst of Frankenstein energy generated I was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957), Frankenstein 1970 (1958; with Karloff as a then-future descendant of Victor Frankenstein) and Frankenstein’s Daughter (1958). Then England’s minor Hammer Studio, like Universal before it, reached for the big time with classic horror thanks to Frankenstein. Since Universal had their Frankenstein Monster makeup and story-lines copyrighted, Hammer went back to Mary Shelley’s novel (sort of) for a whole new approach.

The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), ensured Hammer’s future and was a landmark in the modern horror film history. Christopher Lee plays “The Creature” as a patchwork, brain-damaged man who moves like a broken puppet. The original Creature was pretty thoroughly destroyed in that first film; subsequently the focus of the Hammer series would be on Victor Frankenstein, superbly played by Peter Cushing. The films trace Frankenstein’s ongoing experiments into re-animation and brain transplantation. The latter has become a murderous and increasingly monstrous rationalist.

The Hammer Frankensteins differ from the Universals in their lush color, their convincing 19th century costumes, and their fascination with body parts, living (female) and dead (male). Fisher’s films form a sequence in their own right (only two of the Hammer Frankenstein films — The Evil of Frankenstein, 1964, and The Horror of Frankenstein, 1970 — were not directed by Fisher, and the latter was the only one that did not star Cushing). The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), Frankenstein Created Woman (1966), Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969) and Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1973) can be seen as extrapolation of Shelley’s Frankenstein.

The Monster occasionally appeared in Mexico’s monster-rally-with- masked-wrestlers films of the ‘60s. Japan offered a cute, gigantic young Monster grown from the heart of the original in Frankenstein Conquers the World (1964).

New Frankenstein-related stageplays came out every few years, including The Rocky Horror Show (1974; filmed in 1975 as The Rocky Horror Picture Show), and composer Libby Larsen’s 1990 opera, Frankenstein, The Modern Prometheus.

Mel Brooks and Gene Wilder’s masterpiece, Young Frankenstein (1974), is a loving parody of the first three Universal Frankensteins. In the same tone was Paul Morrissey’s Flesh for Frankenstein (1974). Tim Burton’s 27-minute Frankenweenie (1984) is a clever parody of the first Whale film, in which young Victor Frankenstein (Barret Oliver) reanimates his dog with household appliances only to find that the neighbors hate and fear the reanimated Sparky.

The Bride (1985), a sequel to Bride of Frankenstein, falls short of its considerable ambitions, but Clancy Brown makes a sympathetic Monster. Two ‘80s films claimed to tell the story of the Villa Diodati circle: Ken Russell’s overheated Gothic (1986) and Ivan Passer’s subtler Haunted Summer (1988), the latter featuring a fine portrayal of Mary by Alice Krige. Alas, neither film is much interested in the actual circumstances leading to Mary’s creation of Frankenstein.

Brian Aldiss’ 1974 novel, Frankenstein Unbound, in which Mary and her creations are characters, was filmed, apparently confusingly, as Roger Corman’sFrankenstein Unbound (1990). Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994) is beautifully photographed, and probably comes the closest of any adaptation to the details of the novel (though still not that close). But while Branagh has many of the story’s lyrics, he doesn’t have the tune, and the result feels phoney, with the exceptions of John Cleese’s low-key performance as Dr. Waldman and Robert De Niro’s sincere rendering of the Monster.

In the novel, Victor Frankenstein is a doctor who seems discontent and achieves satisfaction by exploring the supernatural realm. The creation of his monster comes about because of his unchecked intellectual ambition: he had been striving for something beyond his control. Consequently, his ambition is misled and his life becomes a hollow existence.