Salem was divided into a prosperous town second only to Boston and a farming village. The two bickered again and again. The villagers, in turn, were split into factions that fiercely debated whether to seek ecclesiastical and political independence from the town. To understand the events of the Salem witch trials, it is necessary to examine the times in which accusations of witchcraft occurred. There were the ordinary stresses of 17th-century life in Massachusetts Bay Colony.

A strong belief in the devil, factions among Salem Village fanatics and rivalry with nearby Salem Town, a recent small pox epidemic and the threat of attack by warring tribes created a fertile ground for fear and suspicion.

In 1688, after a quarrel between two women called Glower and Goodwin, the child of the latter attending to the violent scene falled in convulsions. Glower, a catholic irish was charged of witchcraft and executed.

In 1689 the villagers won the right to establish their own church and chose the Reverend Samuel Parris, a former merchant, as their minister. His rigid ways and seemingly boundless demands for compensation made him impopular. Many villagers vowed to drive Parris out, and they stopped contributing to his salary in October 1691.

Seeking release from the tension choking their family, Parris’s nine-year-old daughter, Betty, and her cousin Abigail Williams delighted in the mesmerizing tales spun by Tituba, a slave from Barbados. The girls invited several friends to share this delicious, forbidden diversion. Tituba’s audience listened intently as she talked of telling the future.

In January of 1692, the daughter and niece of Reverend Samuel Parris of Salem Village became ill.

She had some kind of convulsions with delirium fits. Then Abigail Williams and the girls’ friend Ann Putnam, followed the same course. Doctors and ministers watched in horror as the girls contorted themselves, cowered under chairs, and shouted nonsense. Lacking a natural explanation, the Puritans turned to the supernatural, the girls were bewitched. Prodded by Parris and others, they named their tormentors: a disheveled beggar named Sarah Good, the elderly Sarah Osburn, and Tituba herself.

Each woman was something of a misfit. Osburn claimed innocence. Good did likewise but fingered Osburn. Tituba, recollection refreshed by Parris’s lash, confessed March 1692 that “The devil came to me and bid me serve him”. Villagers sat spellbound as Tituba spoke of black dogs, red cats, yellow birds, and a white-haired man who bade her sign the devil’s book. There were several undiscovered witches, she said, and they yearned to destroy the Puritans.

Finding witches became a crusade not only for Salem but all Massachusetts. Before long the crusade turned into a convulsion, and the witch-hunters ultimately proved far more deadly than their prey. Anne Putman, is probably one of the key element of the story but we do not have much details concerning this rich hysterical woman who joined the “Circus girls”.

In May of 1692 the Salem Witch Trials began and quickly degenerated into a circus. Among the charges against one alleged witch, Martha Cory, the girls claimed that the alleged witch could wring her own hands and thereby hurt the girls physically. The girls also went into convulsions and other dramatics while in the court room. One of the girls claimed to have “spectral evidence”, in other words, a specter or evil spirit which only the girl perceived but which was invisible to the human eye.

Incredibly enough, this was considered as legitimate evidence of witchcraft by the accused. The “afflicted” were those supposedly “possessed” and “tormented”; it was they who accused or “cried out” the names of those who were supposedly possessing them.

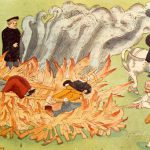

In June of 1692, the special Court of Oyer and Terminer (meaning “hearing and determination”) sat in Salem to hear the cases of witchcraft. Presided over by Chief Justice William Stoughton, the court was made up of magistrates and jurors. The first to be tried was Bridget Bishop of Salem who was found guilty and was hanged on June 10. Nineteen “witches” were hanged at Gallows Hill in 1692, and one defendant, Giles Cory, was tortured to death for refusing to enter a plea at his trial.

Five others, including an infant, died in prison. One man who refused to plead at all in the case, thereby not recognizing the court’s authority, was crushed to death under a large stone. Tituba was jailed then resold and taken out of the Salem Village area.

Soon, however, the public and people in authority became alarmed that the trials were getting out of hand; anyone, it seemed, could be accused of witchcraft. On October 3, 1692, the Reverend Increase Mather, president of Harvard College, considered the most prominent minister in the colony, denounced the use of so-called spectral evidence. “It were better,” Mather admonished his fellow ministers “that ten suspected witches should escape than one innocent person should be condemned.”

Governor William Phips grew disgusted when his own wife was mentioned by the afflicted girls. Determined at last to quell the madness, he suspended the special Court of Oyer and Terminer he had earlier established to hear witchcraft cases. The Superior Court of Judicature, formed to replace the “witchcraft” court, did not allow spectral evidence. This belief in the power of the accused to use their invisible shapes or spectres to torture their victims had sealed the fates of those tried by the Court of Oyer and Terminer.

The new court condemned only 3 of 56 defendants. In May 1693 Phips pardoned all those who were still in prison on witchcraft charges along with five others awaiting execution. In effect, the Salem witch trials were over.

Massachusetts as a whole repented the Salem witch-hunt in stages. The colony observed a day of atonement in 1697. It prompted one of the judges to seek public forgiveness for his role in the trials. That same year time, Reverend Joseph Green succeeded Samuel Parris as minister in Salem Village. Green reshuffled his congregation’s traditional seating plan, placing foes beside one another. As he had hoped, proximity bred charity. At Green’s urging, Ann Putnam, one of the leading accusers, offered a public apology in 1706.

In 1711 the legislature passed a bill restoring the rights and good names of some of the victims of “those dark and severe Prosecutions,”awarding restitution to their heirs”. Massachusetts apologized again in 1957, and the city of Salem and the town of Danvers (originally Salem Village) dedicated memorials to the slain “witches” in 1992.

The only good to come out of this disgrace to the legal system was that eventually other people came to their senses and condemned the Salem Witch Trials. But the stain of the Witch Trials remained. The symbols of authority ( the reverend, the doctor, and the judge) had all participated in this travesty of justice and abomination of morality.

Chronology

January 20 Nine-year-old Elizabeth Parris and eleven-year-old Abigail Williams began to exhibit strange behavior, such as blasphemous screaming, convulsive seizures, trance-like states and mysterious spells. Within a short time, several other Salem girls began to demonstrate similar behavior.

Mid-February Unable to determine any physical cause for the symptoms and dreadful behavior, physicians concluded that the girls were under the influence of Satan.

Late February Prayer services and community fasting were conducted by Reverend Samuel Parris in hopes of relieving the evil forces that plagued them. In an effort to expose the “witches”, John Indian baked a witch cake made with rye meal and the afflicted girls’ urine.

This counter-magic was meant to reveal the identities of the “witches” to the afflicted girls. Pressured to identify the source of their affliction, the girls named three women, including Tituba, Parris’ Carib Indian slave, as witches. On February 29, warrants were issued for the arrests of Tituba, Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne.

Although Osborne and Good maintained innocence, Tituba confessed to seeing the devil who appeared to her “sometimes like a hog and sometimes like a great dog”. What’s more, Tituba testified that there was a conspiracy of witches at work in Salem.

March 1 Magistrates John Hathorne and Jonathan Corwin examined Tituba, Sarah Good, and Sarah Osborne in the meeting house in Salem Village. Tituba confessed to practicing witchcraft. Over the next weeks, other townspeople came forward and testified that they, too, had been harmed by or had seen strange apparitions of some of the community members.

As the witch hunt continued, accusations were made against many different people. Frequently denounced were women whose behavior or economic circumstances were somehow disturbing to the social order and conventions of the time. Some of the accused had previous records of criminal activity, including witchcraft, but others were faithful churchgoers and people of high standing in the community.

March 12 Martha Corey is accused of witchcraft.

March 19 Rebecca Nurse was denounced as a witch.

March 21 Martha Corey was examined before Magistrates Hathorne and Corwin.

March 24 Rebecca Nurse was examined before Magistrates Hathorne and Corwin.

March 28 Elizabeth Proctor was denounced as a witch.

April 3 Sarah Cloyce, Rebecca Nurse’s sister, was accused of witchcraft.

April 11 Elizabeth Proctor and Sarah Cloyce were examined before Hathorne, Corwin, Deputy Governor Thomas Danforth, and Captain Samuel Sewall. During this examination, John Proctor was also accused and imprisoned.

April 19 Abigail Hobbs, Bridget Bishop, Giles Corey, and Mary Warren were examined. Only Abigail Hobbs confessed.

William Hobbs “I can deny it to my dying day.”

April 22 Nehemiah Abbott, William and Deliverance Hobbs, Edward and Sarah Bishop, Mary Easty, Mary Black, Sarah Wildes, and Mary English were examined before Hathorne and Corwin. Only Nehemiah Abbott was cleared of charges.

May 2 Sarah Morey, Lydia Dustin, Susannah Martin, and Dorcas Hoar were examined by Hathorne and Corwin.

Dorcas Hoar “I will speak the truth as long as I live.”

May 4 George Burroughs was arrested in Wells, Maine.

May 9 Burroughs was examined by Hathorne, Corwin, Sewall, and William Stoughton. One of the afflicted girls, Sarah Churchill, was also examined.

May 10 George Jacobs, Sr. and his granddaughter Margaret were examined before Hathorne and Corwin. Margaret confessed and testified that her grandfather and George Burroughs were both witches. Sarah Osborne died in prison in Boston.

Margaret Jacobs “… They told me if I would not confess I should be put down into the dungeon and would be hanged, but if I would confess I should save my life.”

May 14 Increase Mather returned from England, bringing with him a new charter and the new governor, Sir William Phips.

May 18 Mary Easty was released from prison. Yet, due to the outcries and protests of her accusers, she was arrested a second time.

May 27 Governor Phips set up a special Court of Oyer and Terminer comprised of seven judges to try the witchcraft cases. Appointed were Lieutenant Governor William Stoughton, Nathaniel Saltonstall, Bartholomew Gedney, Peter Sergeant, Samuel Sewall, Wait Still Winthrop, John Richards, John Hathorne, and Jonathan Corwin.

These magistrates based their judgments and evaluations on various kinds of intangible evidence, including direct confessions, supernatural attributes (such as “witchmarks”), and reactions of the afflicted girls.

Spectral evidence, based on the assumption that the Devil could assume the “specter” of an innocent person, was relied upon despite its controversial nature.

May 31 Martha Carrier, John Alden, Wilmott Redd, Elizabeth Howe, and Phillip English were examined before Hathorne, Corwin, and Gedney.

June 2 Initial session of the Court of Oyer and Terminer. Bridget Bishop was the first to be pronounced guilty of witchcraft and condemned to death.

Early June Soon after Bridget Bishop’s trial, Nathaniel Saltonstall resigned from the court, dissatisfied with its proceedings.

June 10 Bridget Bishop was hanged in Salem, the first official execution of the Salem witch trials.

Bridget Bishop “I am no witch. I am innocent. I know nothing of it.” Following her death, accusations of witchcraft escalated, but the trials were not unopposed. Several townspeople signed petitions on behalf of accused people they believed to be innocent.

June 29-30 Rebecca Nurse, Susannah Martin, Sarah Wildes, Sarah Good and Elizabeth Howe were tried for witchcraft and condemned.

Rebecca Nurse “Oh Lord, help me! It is false. I am clear. For my life now lies in your hands….”

Mid-July In an effort to expose the witches afflicting his life, Joseph Ballard of nearby Andover enlisted the aid of the accusing girls of Salem. This action marked the beginning of the Andover witch hunt.

July 19 Rebecca Nurse, Susannah Martin, Elizabeth Howe, Sarah Good, and Sarah Wildes were executed.

Elizabeth Howe “If it was the last moment I was to live, God knows I am innocent…”

Susannah Martin “I have no hand in witchcraft.”

Dialogue based on the examination of Sarah Good by Judges Hathorne and Corwin “What evil spirit have you familiarity with? None. Have you made no contract with the devil? No. Why do you hurt these children? I do not hurt them. I scorn it. Who do you imploy then to do it? I imploy no body. What creature do you imploy then? No creature. I am falsely accused. “

August 2-6 George Jacobs, Sr., Martha Carrier, George Burroughs, John and Elizabeth Proctor, and John Willard were tried for witchcraft and condemned.

Martha Carrier “…I am wronged. It is a shameful thing that you should mind these folks that are out of their wits.”

August 19 George Jacobs, Sr., Martha Carrier, George Burroughs, John Proctor, and John Willard were hanged on Gallows Hill.

George Jacobs “Because I am falsely accused. I never did it.”

September 9 Martha Corey, Mary Easty, Alice Parker, Ann Pudeator, Dorcas Hoar, and Mary Bradbury were tried and condemned.

Mary Bradbury “I do plead not guilty. I am wholly innocent of such wickedness.”

September 17 Margaret Scott, Wilmott Redd, Samuel Wardwell, Mary Parker, Abigail Faulkner, Rebecca Eames, Mary Lacy, Ann Foster, and Abigail Hobbs were tried and condemned.

September 19 Giles Corey was pressed to death for refusing a trial.

September 21 Dorcas Hoar was the first of those pleading innocent to confess. Her execution was delayed.

September 22 Martha Corey, Margaret Scott, Mary Easty, Alice Parker, Ann Pudeator, Wilmott Redd, Samuel Wardwell, and Mary Parker were hanged.

October 8 After 20 people had been executed in the Salem witch hunt, Thomas Brattle wrote a letter criticizing the witchcraft trials. This letter had great impact on Governor Phips, who ordered that reliance on spectral and intangible evidence no longer be allowed in trials.

October 29 Governor Phips dissolved the Court of Oyer and Terminer.

November 25 The General Court of the colony created the Superior Court to try the remaining witchcraft cases which took place in May, 1693. This time no one was convicted.

Mary Easty “…if it be possible no more innocent blood be shed… …I am clear of this sin.”

Victims

- Bishop, Bridget Hanged June 10

- Bradbury, Mary Convicted September 6; Escaped

- Burroughs, Rev. GeorgeHanged August 19

- Carrier, Martha Her 7 yr. Old Testified, Hanged August 19

- Cloyce, Sarah Convicted September 6; Reprieved

- Cory, Giles Pressed to death September 19

- Cory, Martha Hanged September 22

- Eames, Rebecca Convicted September 17; Reprieved

- Esty, Mary Hanged September 22

- Faulkner, Abigail Convicted; Pleaded pregnancy

- Foster, Ann Died in jail

- Good, Sarah Charged February 29, Hanged July 19

- Hoar, Dorcas Convicted September 6; reprieved

- Hobbs, Abigail 7 yr. Old testified, Convicted September 6; Reprieved

- How, Elizabeth Hanged July 19 Jacobs,

- George Hanged August 19

- Lacy, Mary Convicted September6; reprieved

- Martin, Susanna Haned July 19

- Nurse, Rebbeca Hanged July 19

- Osborne, Sarah Died in Jail

- Parker, Alice Hanged September 22

- Parker, Mary Hanged September 22

- Proctor, Elizabeth Convicted; Pleaded pregnancy

- Proctor, John Father of 5, Hanged August 19

- Pudeator, Ann Hanged September 22

- Reed, Wilmot Hanged September 22

- Scott, Margaret Hanged September 22

- Tituba (Rev. Samual Parris’ Slave) Held in Jail

- Wardwell, Samuel Confessed then denied it, Hanged September 22

- Wilds, Sarah Hanged July 19

- Willard, John Deputy Constable, Hanged August 19