Vampirism has been described as “a corpse that comes to the attention of the populace in times of crisis.”. Those times of crisis are mostly times of death and suffering such a wars and worse, epidemics.

Folkloric vampirism has typically been associated with a series of deaths due to unindentifiable or mysterious illnesses, usually within the same family or the same small community. The “epidemic pattern” is obvious in the classical cases of Peter Plogojowitz and Arnold Paole, and even more so in the case of Mercy Brown and in the vampire beliefs of New England generally, where a specific disease, plague, tuberculosis, was associated with outbreaks of vampirism.

Following the Black Death of the mid-fourteenth century the plague continued to devastate Western Europe until the eighteenth century. Then is receded to the Eastern European lands, and until the mid-nineteenth century the Ottoman Empire suffered cruelly from the effects of this dread disease.

The violence of this disease was such that the sick communicated it to the healthy who came near them, just as a fire catches anything dry or oily near it. And it went even further. To speak to or go near the sick brought the infection and a common death to the living; and moreover to touch the clothes or anything else the sick person had touched or wore gave the disease to the person touching.

In his book, De masticatione mortuorum in tumulis (1725), Michaël Ranft makes a first attempt to explain folk’s belief in vampires in a natural way. He gives the following explanation when talking about the case of Peter Plogojowitz:

“This brave man perished by a sudden or violent death. This death, whatever it is, can provoke in the survivors the visions they had after his death. Sudden death gives rise to inquietude in the familiar circle. Inquietude has sorrow as a companion. Sorrow brings melancholy. Melancholy engenders restless nights and tormenting dreams. These dreams enfeeble body and spirit until illness overcomes and, eventually, death.”

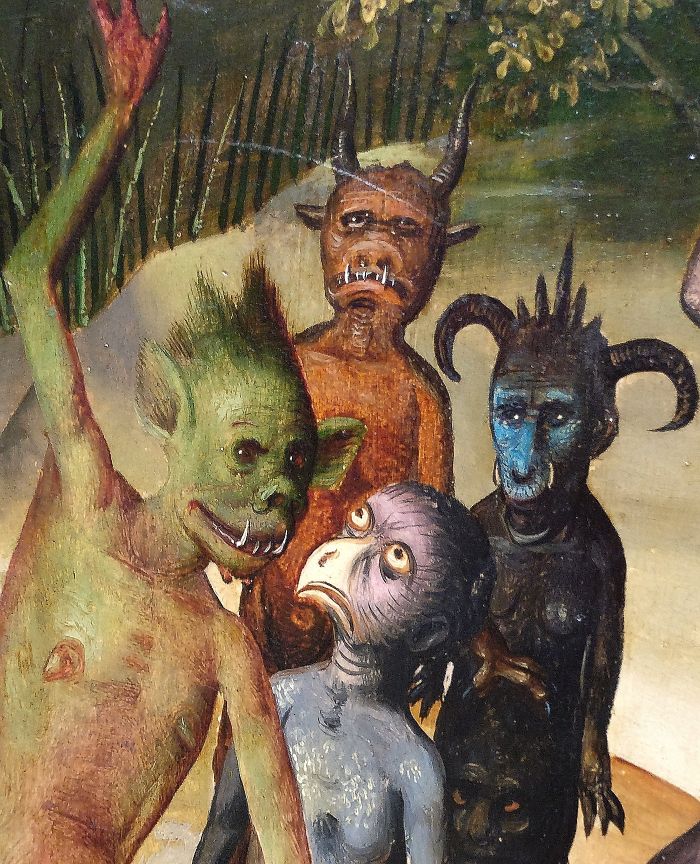

Once it was established that dead bodies– as opposed to spirits of the dead– were the cause of death, the vampire became the icon for the plague. The Church introduced another element of fear with vampires rising from the bodies of suicide victims, criminals, or evil sorcerers, though in some cases an initial vampire thus “born of sin” could pass his vampirism onto his innocent victims.

As personification of Evil and bringers of Death, vampires became the absolute scapegoat to explain the unexplainable.