In Italy besides the traditional dance of death we find spectacular representations of death as the all-conqueror in the so-called “Trionfo della Morte”. The earliest traces of this conception may be found in Dante and Petrarch.

According to Ariès, Death as “the common tyrant,” and triumphing conqueror, was “a symbol of blind fate”, very different, apparently, from the individualism of the dances of death. Whereas Germany and France preferred the dance of Death, Italy liked that genre better.

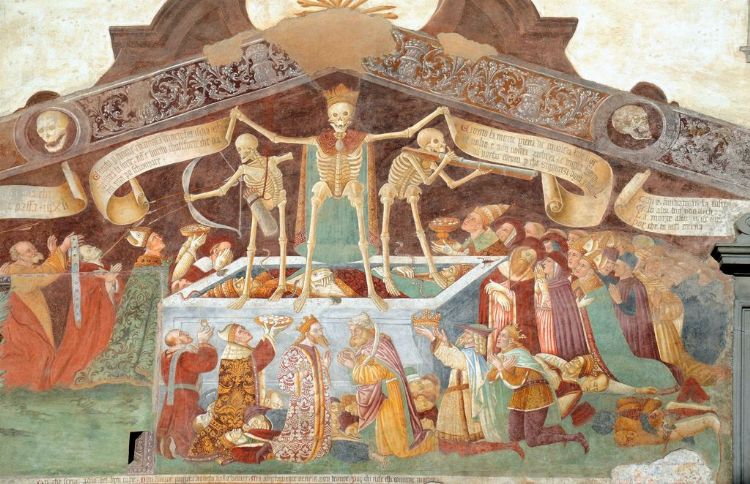

One of the most famous “Triumph of Death” lies in the cemetery of Pisa and was painted between 1450 and 1500. Alessandro Triani’s Triumph of Death (Trionfo della Morte) is another masterpiece of the Sienese period. Painted in 1350, The Triumph of Death depicts rich nobles out for a picnic in the countryside, unaware that the plague (in the shape of a grotesque hag) is ready to strike.

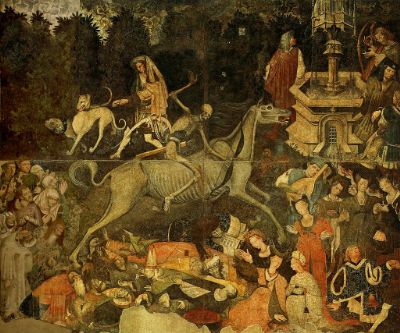

Another famous fresco can be found in the court of Palazzo Sclafani, also in Palermo. Death enters riding a skeletal horse, firing arrows from a bow. Death aims at characters belonging to all social levels, killing them. The horse occupies the center of the scene, with its ribs visible and an emaciated head showing teeth and the tongue. Death has just released an arrow, which has hit a young man in the lower right corner; Death also wears a scythe at the side of the saddle, its typical attribute.

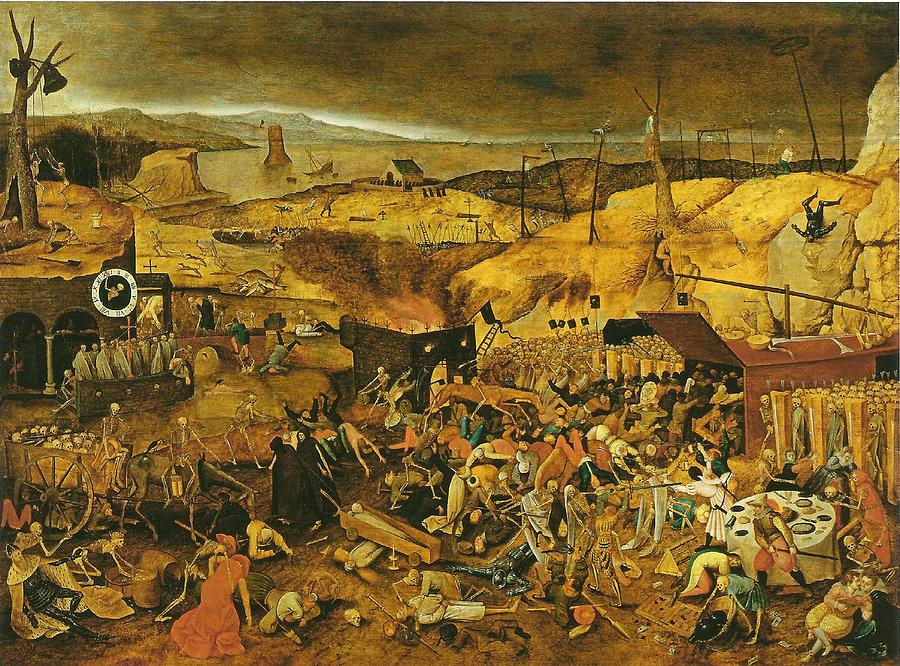

In the Triumph of Death (1562) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, the viewer is confronted with a bleak landscape of death and destruction. An army of skeletons massacres masses of people of every age and gender. At the top of the painting, the sky is black with smoke from fires that have destroyed the landscape, as if the land had been decimated by war. Ships lie half sunken in the bay. The middle of the painting features skeletons herding masses into a spike rimmed tunnel; the door of the tunnel is marked with the holy cross of Christ. There is no suggestion of salvation however, for piles of bones, skulls, and intact skeletons fill pens and wagons, and litter the ground. In the painting’s foreground, people of high social status are sprawled dead or dying near more ordinary individuals — king, cardinal, wanderer, lovers — all, regardless of their social status, meet Death.

On the lower part are corpses of the people previously killed: emperors, popes, bishops, friars (both Franciscans and Dominicans), poets, knights and maidens. Each character is portrayed differently: some still have a grimace of pain on the face, while others are serene; some have their limbs dismembered on the ground, and others are kneeling after having been just struck by an arrow. On the left is a group of poor people, invoking Death to stop their suffering, but being ignored. Among them, the figure looking towards the observer has been proposed as a possible self-portrait of the artist.

On the right, a group of richly dressed noblewomen and knights with fur clothes are entertained by a musician. They appear to have no interest in the events and continue to socialize. The women in this group wear ostentatious necklaces and some are adorned with long, dangling earrings. A sumptuary law passed in Sicily in 1420 prohibited the wearing of expensive gold jewelry, except for rings, and declared that earrings could only be worn at particularly important celebrations. A man with a falcon on his arm and another is leading two hounds represent common pursuits of the noble classes in the Renaissance.

In Florence (1559) the “triumph of death” formed a part of the carnival celebration. We may describe it as follows: After dark a huge wagon, draped in black and drawn by oxen, drove through the streets of the city. At the end of the shaft was seen the Angel of Death blowing the trumpet. On the top of the wagon stood a great figure of Death carrying a scythe and surrounded by coffins. Around the wagons were covered graves which opened whenever the procession halted. Men dressed in black garments on which were painted skulls and bones came forth and, seated on the edge of the graves, sang dirges on the shortness of human life. Before and behind the wagon appeared men in black and white bearing torches and death masks, followed by banners displaying skulls and bones and skeletons riding on scrawny nags. While they marched the entire company sang the Miserere with trembling voices.

Reference

Western Attitudes Toward Death from the Middle Ages to the Present (1975) by Philippe Aries