A number of these “witch hunters” wrote books on witchcraft, including Nicholas Eymeric, the inquisitor in Aragon and Avignon, who published the Directorium Inquisitorum in 1376. The most notable of these works was published in 1487, written by the German Dominican monk, Heinrich Kramer – allegedly aided by Jacob Sprenger – known as the Malleus Malificarum (The Hammer of the Witches) in which they set down the stereotypical image of the Satanic witch and prescribed torture as a means of interrogating suspects. The Malleus Malificarum was reprinted in twenty-nine editions up till 1669.

Jean Bodin (1529-1596)

The humanist philosopher and jurist Jean Bodin was one of the most prominent political thinkers of the sixteenth century. His reputation is largely based on his account of sovereignty which he formulated in the Six Books of the Commonwealth.

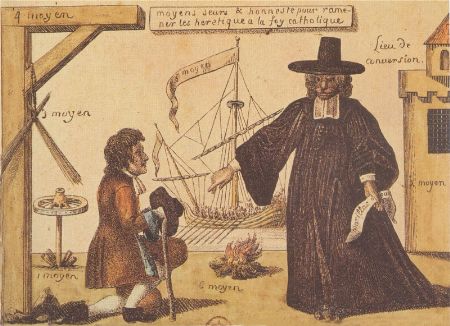

De la démonomanie des sorciers (Of the Demon-mania of the Sorcerers) is Bodin’s major work on sorcery and the witchcraft persecutions. It was first issued in 1580, ten editions being published with translations by 1604. Bodin elaborates the influential concept of “pact witchcraft” based on a deal with the Devil and the belief that the evil spirit would use a strategy to impose doubt on judges to look upon magicians as madmen and hypochondriacs deserving of compassion rather than chastisement.

Bodin had a strong belief in the existence of angels and demons, and believed that they served as intermediaries between God and human beings; God intervenes directly in the world through the activity of angels and demons. Demonism, together with atheism and any attempt to manipulate demonic forces through witchcraft or natural magic, was treason against God and to be punished with extreme severity.

The Démonomanie is divided into four books. Book One begins with a set of definitions. Bodin then discusses to what extent men may engage in the occult, and the differences between lawful and unlawful means to accomplish things. He also discusses the powers of witches and their practices: whether witches are able to transform men into beasts, induce or inspire in them illnesses, or perhaps even bring about their death. The final book is a discussion concerning ways to investigate and prosecute witches. Bodin’s severity and his rigorousness in condemning witches and witchcraft is largely based on the contents of the final book of the Démonomanie.

Bodin may have considered witchcraft an insult against God, and as such meriting the penalty of death, but he nevertheless believed in the rule of law, as in this other passage where he unequivocally states that “it is better to acquit the guilty than to condemn the innocent” (Bodin 2001, 209-210).

Nicholas Remy (1530-1616)

Nicholas Rémy, Latin Remigius (1530–1616) was a French lawyer who claimed in his book to have overseen the execution of more than 800 witches and the torture or persecution of a similar number over a 15-year period in Lorraine, France.

Remy personally sentenced 800 people to death between 1581 and 1591. In 1592, Remy retired and moved to the country to escape the bubonic plague. There he compiled notes from his ten-year campaign against witchcraft a book called

Daemonolatreiae libri tres (“Demonolatry”), written in Latin and published in Lyon in 1595. The book is divided into three parts: a study of Satanism, accounts of the activities of witches, and Remy’s conclusions, based on confessions and evidence obtained in the 800 trials.

Remy discussed the powers, activities, and limitations of Demons. He asserted that witches and Demons were inextricably linked. He described witches’ black magic and spells, the various ways in which they poisoned people, and their infernal escapades with Demons and the Devil. Demons prepared ointments, powders, and poisons for witches to use against human beings and beasts. He devoted much space to describing satanic pacts and the feasting, dancing, and sexual orgies that took place at sabbats. According to Remy, the Devil could appear before people in the shape of a black cat or man, and liked Black Masses. Demons could also have sexual relationships with women and, in case they did not agree, rape them. He described how the Devil drew people into his service, first with cajoling and promises of wealth, power, love, or comfort, then with threats of disaster or death.

His work shows much influence from Jean Bodin. The book was reprinted several times, translated into German, and eventually replaced the Malleus Maleficarum as the most recognized handbook of witch-hunters in parts of Europe. However, it seems that the number of executions has been inflated by Remy and would be more close to 130 than 800 according to historical records.

Matthew Hopkins (ca. 1620 – 1647)

Matthew Hopkins was an English witchhunter whose career flourished during the time of the English Civil War. He claimed to hold the office of Witch-Finder General, although this was not a title ever bestowed by Parliament, and conducted witch hunts mainly in the counties of Suffolk, Essex, Norfolk and occasionally in other eastern counties of England.

In 1647 he printed a pamphlet in his own defense, and then died. This we learn from his coadjutor Sterne, who assures us that he had “no trouble of conscience for what he had done, as was falsely reported of him.” Under the title of A Confirmation and Discovery of Witchcraft, in which he boasts that he had been part and agent in convicting about two hundred witches in Essex, Suffolk, Northamptonshire, Huntingdonshire, Bedfordshire, Norfolk, Cambridgeshire, and the Isle of Ely. He assures us “that in many places I never received penny as yet, nor any am like, notwithstanding I have hands for satisfaction, except I should sure; but many rather fall upon me for what hath been received: but I hope such sues will be disannulled, and that where I have been out of moneys for towns in charges and otherwise, such course will be taken that I may be satisfied and paid with reason.”

Hopkins himself, in defending himself against the charge of interestedness, tells us that his regular charge was 20s. for each town, including the expenses of living, and journeying thither and back. In his book, he confesses that, besides the other practices of stripping the victims naked, and thrusting pins into various parts of their body, in search of marks; and swimming them, – he had practiced the new torture of keeping them awake, and forcing them to walk, which was an invention of his own: but he acknowledges that he had been so far obliged to yield to public opinion in the latter part of his course, as to lay aside this his own favourite remedy.

King James I (1566-1625)

King James VI, who, following the death of Elizabeth I, became King James I of England in 1603 took a special interest in witchcraft. In 1597, King James VI of Scotland published a compendium on witchcraft lore called Daemonologie. It was also published in England in 1603 when James acceded to the English throne.

The book asserts James’s full belief in magic and witchcraft, and aims to both prove the existence of such forces and to lay down what sort of trial and punishment these practices merit – in James’s view, death. Daemonologie takes the form of a dialogue (popular for didactic works) and is divided into three sections: the first on magic and necromancy (the prediction of the future by communicating with the dead), the second on witchcraft and sorcery and the third on spirits and spectres.

Many elements of the witchcraft scenes in Macbeth conform to James’s ideas and beliefs in witchcraft as expressed in Daemonologie, News from Scotland and his anti-witchcraft legislation. This includes ideas such as the witches’ vanishing/invisible flight, their raising of storms, dancing and chanting, sexual acts, their gruesome potion ingredients and the presence of animal familiars.

Scottish Parliament had criminalized witchcraft in 1563, just before James’s birth. The act made being a witch a capital offense. Nearly three decades passed before the first major witchcraft panic arose in 1590, when King James came to believe that he and his Danish bride, Anne, had been personally targeted by witches who conjured dangerous storms to try to kill the royals during their voyages across the North Sea.

One of the first accused in this panic was a woman named Geillis Duncan, from Tranent in East Lothian. In late 1590 her employer, David Seton, accused her and tortured her into a confession in which she named several accomplices. Duncan later retracted her confession, but by then the panic was well under way.

King James sanctioned witch trials after an alarming confession in 1591 from an accused witch, Agnes Sampson. It was revealed that 200 witches—even some from Denmark—had sailed in sieves to the church of the coastal town of North Berwick on Halloween night in 1590. There the devil preached to them and encouraged them to plot the king’s destruction. After hearing these confessions, even though they had been extorted by torture, King James and his advisers came to believe a witchcraft conspiracy threatened his reign.

Six years later another panic broke out. Once again, witches were reported to be conspiring against King James personally. A woman named Margaret Aitken, the so-called great witch of Balwearie, claimed a special power to detect other witches, many of whom were put to death on her word alone. This panic halted abruptly when Aitken was exposed as a fraud. This incident embarrassed witch-hunters greatly, and that same year, partly to justify the recent trials, King James published his treatise, Daemonologie. Witchcraft attracted scholarly interest in the 16th century, and the king’s book reflects how James saw himself as an intellectual. (King James VI is also known for this sacred Christian work: the King James Bible.)

Henri Boguet (1590-1619)

Henry Boguet (1550 in Pierrecourt, Haute-Saône – 1619) was a well known jurist and judge of Saint-Claude (1596–1616) in the County of Burgundy. His renown is to a large degree based on his fame as a demonologist for his “Discours exécrable des Sorciers” (1602) . As a judge over trials for witchcraft, Boguet sent some 600 victims to their deaths in Burgundy, many of them young children who were systematically tortured and then burned alive. In 1598, Boguet presided over a famous werewolf case, the Gandillon family, said to shape-shift into howling, ravenous wolves. Boguet tortured them until they confessed to having sex with the Devil. Three family members were convicted, hanged and burned.

An English translation of Boguet’s Discours de Sorciers, a legal textbook which, with over twelve editions, was a standard for over a century. Based on his own trial experiences it describes over forty cases Bouguet examined and in repute it rivaled the Malleus Maleficarum and surpassed similar works by noted contemporaries like Bodin and Remy.

Part of its success was because of its appendix., “The Manner of Procedure of a Judge in a Case of Witchcraft” which codified existing statutes and court procedures.

Boguet’s family attempted, unsuccessfully, to suppress the work after his death.

Pierre de Lancre (1553 – 1631)

Pierre de Lancre or Pierre de l’Ancre was the French judge of Bordeaux who conducted a massive witch-hunt in Labourd in 1609 and had in less than a year some 70 people burnt at the stake, among them several priests. De Lancre wasn’t satisfied: he estimated that some 3,000 witches were still at large (10% of the population of Labourd in that time). But the Parlement of Bordeaux eventually dismissed him from office.

In his Portrait of the Inconstancy of Witches, de Lancre sums up his rationale as follows:

To dance indecently; eat excessively; make love diabolically; commit atrocious acts of sodomy; blaspheme scandalously; avenge themselves insidiously; run after all horrible, dirty, and crudely unnatural desires; keep toads, vipers, lizards, and all sorts of poison as precious things; love passionately a stinking goat; caress him lovingly; associate with and mate with him in a disgusting and scabrous fashion–are these not the uncontrolled characteristics of an unparalleled lightness of being and of an execrable inconstancy that can be expiated only through the divine fire that justice placed in Hell?

Tarragó

During the seventeenth century, Catalonia will see the emergence of several witch hunters such as Joan Aliberc de Vic or Jaume Font, the Nuncio de Sallent. But surely the most famous witch hunter of the time is Cosme Soler “Tarragó”, a herbalist born in Mas Tarragona de Rialb, in the region of Urgell.

Soler was the instigator of several lawsuits against twelve women from the counties of Lleida around 1616. He was arrested by the Inquisition in 1617, confessing his implications in the trials of Lleida, and released under the promise of never exercising again.

However, in the following years he was the great instigator of most of the processes in Central Catalonia. He performed at Sant Feliu Sasserra in 1618, rubbing shoulders with several women and identifying diabolical marks invisible to the human eye.

“Tarragó” was indirectly responsible for hundreds of executions of women, making a profit with every conviction he got. When the Inquisition and the King ended the persecutions, around 1622,”Tarragó” disappeared for History.

Witchfinders in Africa

In many African societies the fear of witches drives periodic witch-hunts during which specialist witch-finders identify suspects, even today, with death by mob often the result.

Audrey I. Richards, in the journal Africa, relates in 1935 an instance when a new wave of witchfinders, the Bamucapi, appeared in the villages of the Bemba people in Congo. They dressed in European clothing, and would summon the headman to prepare a ritual meal for the village. When the villagers arrived they would view them all in a mirror, and claimed they could identify witches with this method.

These witches would then have to “yield up his horns”; i.e. give over the horn containers for curses and evil potions to the witch-finders. The bamucapi then made all drink a potion called kucapa which would cause a witch to die and swell up if he ever tried such things again. The villagers related that the witch-finders were always right because the witches they found were always the people whom the village had feared all along. The bamucapi utilised a mixture of Christian and native religious traditions to account for their powers and said that God (not specifying which God) helped them to prepare their medicine.

In addition, all witches who did not attend the meal to be identified would be called to account later on by their master, who had risen from the dead, and who would force the witches by means of drums to go to the graveyard, where they would die. Richards noted that the bamucapi created the sense of danger in the villages by rounding up all the horns in the village, whether they were used for anti-witchcraft charms, potions, snuff or were indeed receptacles of black magic.