During medieval times European and Baltic countries were entrenched with werewolf beliefs. Later in the 15th and 16th centuries werewolves, like witches, were thought to be servants of the Devil. They made pacts with the Devil and sold their souls to him for his help. Outlaws and bandits played on these superstitions by sometimes wearing wolfskins over their armour; suspected lycanthropists were burned alive if convicted.

Stories about the werewolf were widely believed in Europe during the Middle Ages.

Fincelius relates also that, in 1542, there was such a multitude of were-wolves about Constantinople that the Emperor, accompanied by his guard, left the city to give them a severe correction, and slew one hundred and fifty of them.

Spranger speaks of three young ladies who attacked a labourer, under the form of cats, and were wounded by him. They were found bleeding in their beds next morning.

Majolus relates that a man afflicted with lycanthropy was brought to Pomponatius. The poor fellow had been found buried in hay, and when people approached, he called to them to flee, as he was a were wolf, and would rend them. The country-folk wanted to flay him, to discover whether the hair grew inwards, but Pomponatius rescued the man and cured him.

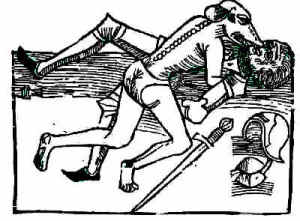

Bodin tells some were-wolf stories on good authority; it is a pity that the good authorities of Bodin were such liars, but that, by the way. He says that the Royal Procurator-General Bourdin had assured him that he had shot a wolf, and that the arrow had stuck in the beast’s thigh. A few hours after, the arrow was found in the thigh of a man in bed. In Vernon, about the year 1566, the witches and warlocks gathered in great multitudes, under the shape of cats. Four or five men were attacked in a lone place by a number of these beasts. The men stood their ground with the utmost heroism, succeeded in slaying one puss, and in wounding many others. Next day a number of wounded women were found in the town, and they gave the judge an accurate account of all the circumstances connected with their wounding.

Bodin quotes Pierre Marner, the author of a treatise on sorcerers, as having witnessed in Savoy the transformation of men into wolves. Nynauld (1) relates that in a village of Switzerland, near Lucerne, a peasant was attacked by a wolf, whilst he was hewing timber; he defended himself, and smote off a fore-leg of the beast. The moment that the blood began to flow the wolf’s form changed, and he recognized a woman without her arm. She was burnt alive.

[1. NYNAULD, De la Lycanthropie. Paris, 1615, p. 52.]

An evidence that beasts are transformed witches is to be found in their having no tails. When the devil takes human form, however, he keeps his club-foot of the Satyr, as a token by which he may be recognized. So animals deficient in caudal appendages are to be avoided, as they are witches in disguise. The Thingwald should consider the case of the Manx cats in its next session.

Forestus, in his chapter on maladies of the brain, relates a circumstance which came under his own observation, in the middle of the sixteenth century, at Alcmaar in the Netherlands. A peasant there was attacked every spring with a fit of insanity; under the influence of this he rushed about the churchyard, ran into the church, jumped over the benches, danced, was filled with fury, climbed up, descended, and never remained quiet. He carried a long staff in his hand, with which he drove away the dogs, which flew at him and wounded him, so that his thighs were covered with scars. His face was pale, his eyes deep sunk in their sockets. Forestus pronounces the man to be a lycanthropist, but he does not say that the poor fellow believed himself to be transformed into a wolf. In reference to this case, however, he mentions that of a Spanish nobleman who believed himself to be changed into a bear, and who wandered filled with fury among the woods.

Donatus of Altomare (1) affirms that he saw a man in the streets of Naples, surrounded by a ring of people, who in his were-wolf frenzy had dug up a corpse and was carrying off the leg upon his shoulders. This was in the middle of the sixteenth century.

[1. De Medend. Human. Corp. lib. i. cap. 9.]

France in particular seems to have been infested with werewolves during the 16th century and even enacted edicts which banned the practice of lycanthropy. Many cases that were brought to the courts involved murder and cannibalism. Many were convicted of killing children and eating parts of their bodies. One man took some of the flesh of a little girl home to his wife.

In some of the cases e.g. those of the Gandillon family in the Jura, the tailor of Chalons and Roulet in Angers, all occurring in the year 1598, there was clear evidence against the accused of murder and cannibalism, but none of association with wolves; in other cases, as that of Gilles Garnier in Dole in 1573, there was clear evidence against some wolf, but none against the accused.

Yet while this lycanthropy fever, both of suspectors and of suspected, was at its height, it was decided in the case of Jean Grenier at Bordeaux in 1603 that lycanthropy was nothing more than an insane delusion.

From this time the loup-garou gradually ceased to be regarded as a dangerous heretic, and fell back into his pre-Christian position of being simply a “man-wolf-fiend”.

Some werewolf lore is based on documented events. The Beast of Gevaudan was a creature that reportedly terrorized the general area of the former province of Gevaudan, in today’s Lozere departement, in the Margeride Mountains in south-central France, in the general timeframe of 1764 to 1767. It was often described as a giant wolf and was said to attack livestock and humans indiscriminately.

In England, however, where at the beginning of the 17th century the punishment of witchcraft was still zealously prosecuted by James I of England, the wolf had been so long extinct that that pious monarch was himself able to regard “warwoolfes” as victims of delusion induced by “a natural superabundance of melancholic”. Only small creatures such as the cat, the hare and the weasel remained for the malignant sorcerer to transform himself into, but he was firmly believed to avail himself of these agencies.