Ars moriendi (“The Art of Dying”) is the name of two related Latin texts dating from 1415 and 1450 which offers advice on the protocols and procedures of a good death and on how to “die well”, according to Christian precepts of the late Middle Ages. It was written within the historical context of the effects of the macabre horrors of the Black Death and consequent social upheavals of the 15th century.

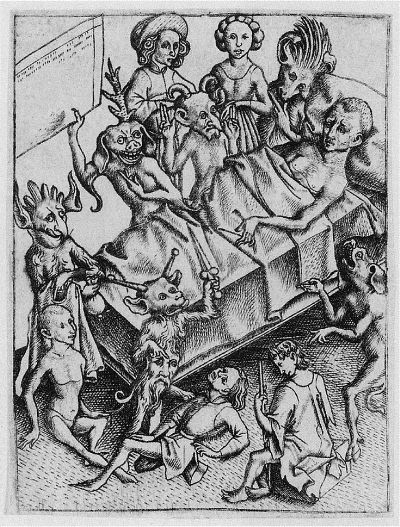

Ars moriendi was also among the first printed books and was widely circulated, in particular in Germany. They appeared in many block-book editions, translated into most West European languages (both words and pictures cut on the same wood block) in the late fifteen century, depicted the struggle between vices (and religious doubts) and virtues (religious certainty) in the mind of the dying man and the fight between externalized good and evil forces over his soul. In medieval belief, demons lay in wait at the bedside of the dying in hopes of snatching away their souls.

Artes moriendi are more refined illustrations that appears in the livres d’heures.

Structure

There was originally a “long version” and then a later “short version” containing eleven woodcut pictures as instructive images which could be easily explained and memorized.

The original “long version”, called Tractatus (or Speculum) artis bene moriendi, was composed in 1415 by an anonymous Dominican monk, probably at the request of the Council of Constance (1414–1418, Germany). It was widely read and translated into most West European languages, and was very popular in England where a literary tradition based on it survived until the 17th century Holy Living and Holy Dying which was the “artistic climax” of the consolatory death literature tradition that had begun with Ars moriendi (Nancy Lee Beaty, 1970). Other works in the English tradition include The Waye of Dying Well and The Sick Mannes Salve.

Ars moriendi consists of six chapters:

- The first chapter explains that dying has a good side, and serves to console the dying man that death is not something to be afraid of.

- The second chapter outlines the five temptations that beset a dying man, and how to avoid them. These are lack of faith, despair, impatience, spiritual pride, and avarice.

- The third chapter lists the seven questions to ask a dying man, along with consolation available to him through the redemptive powers of Christ’s love.

The fourth chapter expressed the need to imitate Christ’s life.

The fifth chapter addresses the friends and family, outlining the general rules of behavior at the deathbed. - The sixth chapter includes appropriate prayers to be said for a dying man.

The “short version”, whose appearance coincides with the introduction of block books (books printed from carved blocks of wood, both text and images), first dates to around 1450, from the Netherlands. It is mostly an adaptation of the second chapter of the “long version”, and contains eleven woodcut pictures. The first ten woodcuts are divided into 5 pairs, with each set showing a picture of the devil presenting one of the 5 temptations, and the second picture showing the proper remedy for that temptation. The last woodcut shows the dying man, presumably having successfully navigated the maze of temptations, being accepted into heaven, and the devils going back to hell in confusion.

Uses

The ars moriendi tradition involved treatment of death as an enemy on one hand, and as gate to immortality on the other, macabre realism (contemptus mundi) and death as both leveler and non-leveler (death not only makes us equal but treats different classes differently).

For theologians and preachers, death was a matter of daily remembrance, related to everyday chores. Mastering the art of dying well was the ultimate aim of every pious Christian. The need to prepare for one’s death was well known in Medieval literature through death-bed scenes, but before the 15th century there was no literary tradition on how to prepare to die, on what a good death meant, or on how to die well. The protocols, rituals and consolations of the death bed were usually reserved for the services of an attending priest. But because of the Black Death, the ranks of the clergy had been particularly hard hit and this is why the Church started disseminating such literature.

In the preparation for a “perfect death”, the artes moriendi served as a part of rhetoric of warning which exploited both natural and supernatural terrors in depicting punishments. Living well and preparing for good death meant a regular routine of the memento mori exercises including prayer, reflection and meditation, mortification of the flesh and self-flagellation.

Funeral sermons adapted and disseminated the artes moriendi from a clerical community to a wider listening public. Deriving their ideas from the accumulated heritage of Christian theology, funeral sermons, as well as treatises on the art of dying, presented not only death’s unrelenting message to a man or a woman (the human certainty of uncertainty) but also a consolation of dying well.