Undead in antiquity

In folkloric sources as diverse as Babylonian literature, the shroud-eating Nachzehrer of Germanic tradition, and the Chiang-Shih “hopping vampires” of Chinese legend, notions of corpses rising from the grave have long been documented.

The Ancient Greeks may have been the first civilization terrorized by a fear of the undead. Archaeologists have unearthed many ancient graves which contained skeletons pinned down by rocks and other heavy objects.

The Epic of Gilgamesh of ancient Sumer includes a mention of zombies. Ishtar, in the fury of vengeance says:

Father give me the Bull of Heaven,

So he can kill Gilgamesh in his dwelling.

If you do not give me the Bull of Heaven,

I will knock down the Gates of the Netherworld,

I will smash the doorposts, and leave the doors flat down,

and will let the dead go up to eat the living!

And the dead will outnumber the living!

The Draugr of medieval Norse mythology were also believed to be the corpses of warriors returned from the dead to attack the living. The zombie appears in several other cultures worldwide, including China, Japan, the Pacific, India, and the Native Americans.

Undead in medieval times

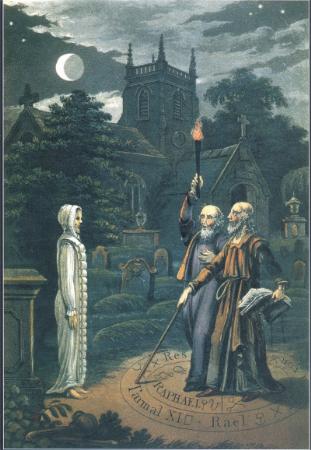

In the Middle Ages, it was a common folk belief that corpses could rise out of their graves and cause havoc to the living, spreading disease and attacking violently. Those who had led an “evil” life or had a score to settle with the living were especially prone to this behavior.

Medieval writers documented that people were advised to decapitate, burn, or obliterate the body by any means necessary to prevent this from happening. This idea of corpses which move around” seems to have been imported into western Europe from Slavic areas.

This shift coincided with devastating plagues that swept across Europe beginning in 1347, killing millions across the continent.

German tales tell of nachzehrer (loosely translated as corpse devourers), and wiedergänger (“those who walk again”), which may have been inspired by mass deaths resulting from the plague.

The revenant usually took on the form of an emaciated corpse or skeletal human figure, and wandered around graveyards at night.

Bulgaria has had multiple cases of 700-year-old skeletons with ploughshares—the hefty blade of a plough—thrust through them into the ground. Recent Polish excavations unearthed skeletons with sickles placed around their waists or the necks.

Other techniques—such as “stoning” (weighing the corpse down with heavy objects)—have been found all over the world, from 4,000-year-old Bronze Age burials pinned down with huge rocks, to graves from Ancient Greece weighted down with amphora fragments, to medieval English skeletons buried under grinding stones.

The approach of ramming something firmly in a corpse’s open jaw has been observed both in 8th-century Irish “zombie burials” and the grave of the “Vampire of Venice,” a 16th-century skeleton disinterred from a plague cemetery with a large sized brick wedged between the teeth.

The Haitian zombi

1697 The word ‘zombi’ first appeared in Le Zombi du grand Perou by Corneille Blessebois. A woman is tricked into thinking she’s an invisible spirit called a zombi. Back then, zombis were spirits or ghosts, not the walking dead as we know them today.

1726 The word ‘zumbi’ appears with a meaning closer to how we use it today in A History of the Voyages and Travels of Capt. Nathaniel Uring. The word ‘zumbi’ refers to the apparition of the dead person, but they walk around and torment the living, much like contemporary zombies.

1819 Robert Southey publishes History of Brazil, in which ‘zombi’ refers to the elected chief of the maroons in Pernambuco. Southey means the guy behaves like he doesn’t have any free will. These early zombie stories were influenced by colonialism. In this era, the zombie characters themselves allude to savage and unintelligent “colonial objects”.

1838 The word zombie first appeared in print in an American newspaper in a reprinted short story called “The Unknown Painter” in 1838.

1928 The word zombie became mainstream in English after W. B. Seabrook published The Magic Island.

The zombie belief has its roots in traditions brought to Haiti by enslaved Africans and their subsequent experiences in the New World. Slaves brought with them the roots of voodoo tradition, the origins of which can be traced back to nearly 6,000 years ago in West Africa. The French then forced them to convert to Christianity, causing the interesting combination of Catholicism and pagan tradition that is associated with Voodoo today.

It was thought that the voodoo deity Baron Samedi would gather them from their grave to bring them to a heavenly afterlife in Africa (“Guinea”), unless they had offended him in some way, in which case they would be forever a slave after death, as a zombie. English professor Amy Wilentz has written that the modern concept of Zombies was strongly influenced by Haitian slavery. Slave drivers on the plantations, who were usually slaves themselves and sometimes voodoo priests, used the fear of zombification to discourage slaves from committing suicide.

While most scholars have associated the Haitian zombie with African cultures, a connection has also been suggested to the island’s indigenous Taíno people, partly based on an early account of native shamanist practices written by the Hieronymite monk Ramón Pané, a companion of Christopher Columbus.

In Haitian culture zombies are not evil creatures but victims. They are said to be people who have been killed by poisoning, then reanimated and controlled by bokors with magic potions for some specific purpose, usually to work as slave labour. The bokors were widely feared and respected. It is said that they used to be in the service of the secret police and those who defied the authorities were threatened with being turned into the living dead.

The Haitian zombie phenomenon first attracted widespread international attention during the United States occupation of Haiti (1915–1934), when a number of case histories of purported “zombies” began to emerge. The first popular book covering the topic was William Seabrook’s The Magic Island (1929). However, local Haitian workers had been writing fiction tales and stories on the subject since the 19th century. Seabrook collected stories about zombies and voodoo and he even thought he saw a dead man resurrected once. Readers in the West were intrigued by these stories, especially Protestant readers and the word became known internationally.

The Serpent and the Rainbow

In 1980, a vacant-eyed man approached Angelina Narcisse in a market, claiming to be her brother, Clairvius Narcisse. The strange thing was that Angelina had buried her brother Clairvius in 1962. The man in front of her claimed to have been resurrected by a witch doctor and was enslaved on a sugar plantation for the last 18 years.

In 1962, Clairvius had checked into Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Desjardins, Haiti, complaining of body aches and a fever. His condition rapidly deteriorated and within a few days, he was declared dead by doctors.

According to the Clairvius who reappeared in 1980, he remembered the whole ordeal, including the doctors pulling the sheet over his face – except he was paralyzed, not dead. He was awake as he was nailed into his coffin and buried.

Clairvius was able to answer questions that only he would know, and his identity was confirmed by several family members. The purported reason for his prolonged absence was due to a two-year enslavement as a zombie by a bokor. However, after the bokor died, Clairvius remained in hiding as he believed that his brother had sold him to the bokor over a land dispute. It was only after his brother’s death that he decided to return.

Wade Davis, a Harvard scientist, investigated the claim and obtained something called ‘zombie powder’ from Haitian bokors. The main active ingredient was a neurotoxin found in puffer fish which could be used to simulate death. The bokors also explained to Davis that a second poison, made from the datura plant, known as the zombie cucumber, was given to victims after they were revived from their death-like state. This kept the ‘zombies’ in a submissive state so that it was easy to force them to work. Davis wrote several books on the topic, including The Serpent and the Rainbow, later made into a horror film by director Wes Craven.

Although the book was very popular with the public, some scientists were skeptical of Davis’s claims. They said the amounts of toxin in the powder samples he found were inconsistent and not high enough to produce zombifying effects. Although many people in Haiti still believe in zombies, there have been no publicized cases in the last few decades and Davis’s theory remains controversial.

The Hollywood zombie

A new version of the zombie, distinct from that described in Haitian folklore, emerged in popular culture during the latter half of the 20th century. This interpretation of the zombie is drawn largely from George A. Romero’s film Night of the Living Dead (1968), which was partly inspired by Richard Matheson’s novel I Am Legend (1954). The word zombie is not used in Night of the Living Dead, but was applied later by fans. After zombie films such as Dawn of the Dead (1978) and Michael Jackson’s music video Thriller (1983), the genre waned for some years.

In 1996 the first game in the Resident Evil series (also known as Biohazard) debuted, in which protagonists attempt to navigate a zombie apocalypse caused by a virus. Several sequels were released for various game consoles, as well as a series of films based on the games. The House of the Dead, a light-gun arcade game, was released the following year. It also spawned several sequels and a big-screen adaptation in 2003. The popularity of zombie video games also contributed in part to the rise of Asian zombie films, including Hong Kong’s Bio-Zombie (1998) and many more in Japan. Video games with their more scientific and action-oriented approach introduced the fast-running and smarter zombies, leading to a resurgence of zombies in popular culture.

Zombie books began to appear more and more frequently, with author Max Brooks releasing both the tongue-in-cheek The Zombie Survival Guide: Complete Protection from the Living Dead (2003) and the best-selling apocalyptic novel World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War (2006; film 2013). Horror icon Stephen King even published a zombie novel during this time, Cell (2006). Also of note was Seth Grahame-Smith’s Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (2009), which took Jane Austen’s public-domain text and added a horror-spoof twist, and the comic book series The Walking Dead, which began in 2003 and was adapted for TV in 2010.

The “zombie apocalypse” concept, in which the civilized world is brought low by a global zombie infestation, has since become a staple of modern popular art. Zombie films and video games continued to gain popularity, with the zombie menace shifting from a shambling mob to rage-filled sprinters in Danny Boyle’s apocalyptic 28 Days Later (2002; followed by 28 Weeks Later [2007]) and Zack Snyder’s big-budget remake of Dawn of the Dead (2004) and in video games such as Dead Rising (2006) and Left 4 Dead (2008), both of which were followed by popular sequels.

Zombie comedy also experienced a revival, with self-proclaimed British “rom-zom-com” (romantic-zombie-comedy) Shaun of the Dead (2004), which lampooned aspects of the zombie genre, paving the way for comedies such as Fido (2006), Dead Snow (2009; Norwegian: Død snø), and the box-office hit Zombieland (2009).

The late 2000s and 2010s saw the humanization and romanticization of the zombie archetype, with the zombies increasingly portrayed as friends and love interests for humans. Notable examples of the latter include movies Warm Bodies and Zombies, novels American Gods by Neil Gaiman, Generation Dead by Daniel Waters, and Bone Song by John Meaney, animated movie Corpse Bride, TV series Pushing Daisies and iZombie, and manga/novel/anime series Sankarea: Undying Love and Is This a Zombie?

Large cities around the world were taken over by “zombie walks,” mobs—sometimes spontaneously organized—of people in zombie costume; some people offered zombie fitness classes or materials, through which participants learned skills that would purportedly help them survive a zombie apocalypse.

On 18 May 2011, the United States’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a graphic novel Preparedness 101: Zombie Apocalypse providing tips to survive a zombie invasion as a “fun new way of teaching the importance of emergency preparedness”. The CDC goes on to summarize cultural references to a zombie apocalypse. It uses these to underscore the value of laying in water, food, medical supplies, and other necessities in preparation for any and all potential disasters, be they hurricanes, earthquakes, tornadoes, floods, or hordes of zombies.

In 2011, the U.S. Department of Defense drafted CONPLAN 8888, a training exercise detailing a strategy to defend against a zombie attack.