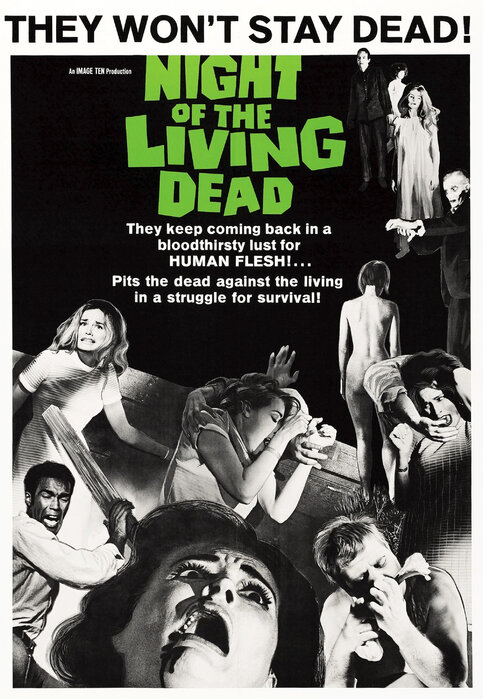

In 1968 director George Romero released the independent black-and-white zombie film Night of the Living Dead. The story, which was cited as groundbreaking, was the first modern zombie film. Although not the first zombie film, Night of the Living Dead was the predecessor of many films with the same plot. Pre-1968 zombies were something entirely different. This film defined the genre forever, made George Romero’s career, and also rocketed Roger Ebert to national stardom (he wrote an angry column about children left by their parents at theaters showing this film, and when it was reprinted by Reader’s Digest, it made him a household name).

As many film historians have pointed out, horror prior to Romero’s film had mostly involved rubber masks and costumes, cardboard sets, or mysterious figures lurking in the shadows. They were set in locations far removed from urban and suburban America. The George Romero arisen ones had the look of “every day”. Their dress consisted of either the clothes that they wore in the casket at their funeral, or normal work clothes (i.e. waitress, mechanic). Injuries such as missing limbs were also common. Their intelligence was very low, and movement stiff and slow. While the word zombie is never used, but Romero’s film introduced the theme of zombies as reanimated, flesh-eating cannibals.

After Night of the Living Dead, the zombie movie genre exploded. Zombies were created in all sort of ways, from radiation to animal bites, and they appeared in all sorts of genres: comedies, mysteries, and action films. Zombies also continued to be used as the finger to point at the evils of the day. After Nazis, big industry was at fault for spilling toxic, or the military was to blame for trying to create a perfect soldier.

The seventies were a decade that saw a lot of zombie movies but originality or quality were left apart. The better films of the decade seemed to come from the minds of European film makers. Europe produced such gems as Tombs of the Blind Dead (1971) and Horror Rises From the Tomb ( 1973). Skulls, some residual facial hair and monk robes were standard fare for the deadly derelicts from the Old Continent.

In Dawn of the Dead (1978), Romero stayed true to his original vision with normal clothing. Now in color, the faces are a bluish tint, and random injuries and blood mark the Romero zombie. Ken Foree exudes calming authority as Peter, the S.W.A.T. team leader who anchors a foursome of refugees who hole up in a shopping mall after humanity discovers “there’s no more room in hell.”

This film is superior to its predecessor in almost every way. The inevitability of the lurching undead is jacked up a notch because we know that the seeming victory at the end of the earlier film was a lie. The claustrophobia is improbably more evident; there’s something about that abandoned mall that screams isolation. And the social anti-consumerist commentary is on full display. This is one of the great social critiques of the 1970s.

Zombi 2 from Lucio Fulci (1979-Italy) is another landmark. It is supposed to be a “sequel” to Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, which was released in Italy as simply “Zombi.” instead. Not only is this movie popular and considered “essential viewing” but it also helped director Lucio Fulci break into the international market.The flick follows a group of people searching for a missing man on a tropical island where a doctor is desperately searching for the cause of a recent epidemic. Zombi 2 is known for its sensational zombie antics such as the notorious eye-gouging, and jugular-biting moments, as well as zombie vs. shark wrestling!