Los Dias de los Muertos, the Days of the Dead, is a traditional Mexico holiday honoring the dead. It is celebrated every year at the same time as Halloween and the Christian holy days of All Saints Day and All Souls Day (November 1st and 2nd). Los Dias de los Muertos is not a sad time, but instead a time of remembering and rejoicing, a family event to remember ancestors, whose spirits visit the earth once a year.

Dia de Los Muertos traditions vary from town to town because Mexico is not culturally monolithic. Things are very different from Yucatan to Central Mexico to the northwest to Northern Mexico.

Origins

More than 500 years ago, when the Spanish Conquistadors landed in what is now Mexico, they encountered natives practicing a ritual that seemed to mock death.

The Aztec Festival of the Dead was originally a two-month celebration during which the fall harvest was celebrated, and figures of “death” were personified as well as honored. The festival was presided over by Mictecacíhuatl, Goddess of the Dead and the Underworld, also known to the Aztecs as Mictlán.

In the pre-Columbian belief system, Mictlán was not dark or macabre, but rather a peaceful realm where souls rested until the days of visiting the living, or los Días de los Muertos, arrived. Over the course of the festivities, participants place offerings for the dead in front of homemade altars, including special foods, traditional flowers, candles, photographs, and other offerings.

It was a ritual the indigenous people had been practicing at least 3,000 years. A ritual the Spaniards would try unsuccessfully to eradicate.

Unlike the Spaniards, who viewed death as the end of life, the natives viewed it as the continuation of life. Instead of fearing death, they embraced it. To them, life was a dream and only in death did they become truly awake. However, the Spaniards considered the ritual to be sacrilegious. They perceived the indigenous people to be barbaric and pagan.

Pre-Hispanic cultures believed that during these days of the year the souls of the departed would return to the realm of the living, where they could visit their loved ones. With the arrival of the Spanish and Christianity, the new rulers of Mexico attempted to marshal the celebrations dedicated to the dead under the auspices of All Saints Day (November 1st), and All Souls Day (November 2nd). The dates of these two Catholic holidays are now celebrated in Mexico as los Días de los Muertos

Previously it fell on the ninth month of the Aztec Solar Calendar, approximately the beginning of August, and was celebrated for the entire month.

Customs

November 1st is a day to remember the children who died before experiencing the joys and sorrows of adulthood. Church bells toll in towns across Mexico early in the morning, to call on the souls of deceased children, or angelitos (little angels), to visit their living loved ones early in the day. In the evening of November 2nd, the more involved celebration begins, to welcome the visit of deceased adults.

The celebration includes an invitation for the dead to return to their family home for a visit. Families welcome them back by placing photographs of their deceased loved ones on altars, and may even write and dedicate poems to them. The celebration includes offerings of cempasúchil flowers, drinks and food for the deceased placed alongside their photographs and poems. They bring toys for dead children and bottles of mescal to adults.

Another traditional practice is the making of the bread of the dead and the sugar, colorful calaveras (skulls), decorated and labeled with names of people (living or dead). The ritual has special significance for those who have lost a loved one during the previous year, since the festival provides a way of coming to terms with their departure.

Extended families will often gather in cemeteries on the eve of November 2nd, el Día de los Muertos, and congregate at the gravesite of a deceased loved one to hold a commemorative feast. The family may keep a night-long vigil by eating the foods they have made in preparation for the celebration, visiting with each other, and praying for all the members of the extended family, both living and dead. Some bring guitars and radios to listen to. The families will spend the entire night in the cemeteries.

The creation of the altar is an integral part of the celebration, with many of the ceremonial objects and familiar signature items of Mexican culture to many outside of the country. Altars are often decorated with flowers, whose brief life span is meant to be a reminder of the brevity of life and whose bright, earthly colors are believed to be a guide for the dead back to their loved ones. Brightly colored and intricately cut tissue paper decorates the altar, waving like multi-colored flags. Offerings of sweets, fruits, and other foods are joined by the staples of bread, salt, and water. Grooming supplies, such as a washbasin and soap, may be provided for the spirits to tidy themselves up after their long journey.

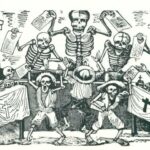

Personal possessions of deceased relatives are placed on an altar. Handmade skeleton figurines, called calacas, are especially popular. Calacas are representations of skeletons participating in the activities of the living, like cooking, dancing, or even playing in mariachi bands and usually show an active and joyful afterlife. Figures of musicians, generals on horseback, even skeletal brides, in their white bridal gowns marching down the aisles with their boney grooms.

The townspeople dress up as ghouls, ghosts, mummies and skeletons and parade through the town carrying an open coffin. The “corpse” within smiles as it is carried through the narrow streets of town. The local vendors toss oranges inside as the procession makes its way past their markets. Lucky “corpses” can also catch flowers, fruits, and candies. Skeletons and skulls are found everywhere. Chocolate skulls, marzipan coffins, and white chocolate skeletons. Special loaves of bread are baked, called pan de muertos, and decorated with “bones.

Ofrendas

All over Mexico, ofrendas or altars are set up in homes and cemeteries on Oct. 30 and 31. They are covered with flowers, fruits, vegetables, candles, incense, statues of saints, photos of the deceased.

On the ofrenda, the main objects are symbolic of life’s elements: water, wind, fire, and earth. Water is served in a clay pitcher or glass to quench the spirit’s thirst from their long journey. Fire is signified by the candles that are lit. Wind is signified by papel picado (tissue paper cut-outs). The earth element is represented by food, usually pan de muerto (bread of the dead). Other offerings include mole, fruit, chocolate, atole, toys, calaveritas de azúcar, and copal incense.

Sugar skulls are decorated with sugar flowers, designs and have, sometimes, the name of the loved one written on the forehead. They represent death and the sweetness of life.

Pan the muerto is especially made to place on the ofrendas and graves. It’s sweet bread flavored with anis and orange peel. It’s baked in a round shape like a skull. It symbolizes the main state of human life.

Traditionally, the flowers used are marigolds, and the incense used on the altar is copal, the resin from a particular tree. Like moles and chile-laced dishes prepared for some of the ancestors, the flowers are quite aromatic and the copal has a distinctive smell.

Papel picado are tissue paper banners with cut out designs of animated skeleton figures. They decorate ofrendas, homes, streets and buildings. They symbolize the wind, one of the elements of life.

Skulls

The use of skulls is inherited from the Aztec ritual. The Aztecs and other Meso-American civilizations kept skulls as trophies and displayed them during the ritual. The skulls were used to symbolize death and rebirth.

The skulls were used to honor the dead, whom the Aztecs and other Meso-American civilizations believed came back to visit during the monthlong ritual.

Today, people don wooden skull masks called calacas and dance in honor of their deceased relatives. The wooden skulls are also placed on altars that are dedicated to the dead. Sugar skulls, made with the names of the dead person on the forehead, are eaten by a relative or friend.

The popular use of skelettons was also inspired from the work of Mexican press artist Jose Guadalupe Posada, who died in 1913. Posada inspired muralist Diego Rivera and others with his caricatures of the rich and political, all depicted as skeletons. Katarina, a skeletal figure in a plumed hat and dress, has become the instant visual signal of El Dia de Los Muertos.

Butterflies

Every autumn Monarch Butterflies, which have summered up north in the United States and Canada, return to Mexico for the winter protection of the oyamel fir trees. The locale inhabitants welcome back the returning butterflies, which they believe bear the spirits of their departed.

The spirits to be honored during Los Dias de los Muertos.The Aztecs believed in an afterlife where the spirits of their dead would return as hummingbirds and butterflies. Even images carved in the ancient Aztec monuments show this belief – the linking the spirits of the dead and the Monarch butterfly.

Día de las Ñatitas

Most countries of Latin America follow Mexico’s traditions regarding the celebrations for the Day of the Dead. But in Bolivia this celebration has a twist, as they celebrate “Día de las Ñatitas” or “Day of the Skulls,” which is why they use skulls during such events, and no, they are not made of candy, plastic or other material, they are real human skulls.

People usually obtain the skulls from medical professionals or even from cemeteries. After they have them, they are decorated with jewelry. The next step is to take them to the annual mass that is considered to bring good luck. Image credit: Natibainotti.

The Novena

The Philippines, a former colony of Spain, celebrates these days in a similar way. They attend to mass and “Novena,” to offer prayers to a particular dead relative or friend. The families also go to cemeteries and decorate the graves. Sometimes they also eat and drink around the grave.

According to the beliefs, the souls of the dead ones return to the Earth during these moments, so their living family makes them feel as comfortable and welcomed as possible.