The hunter may be an unidentified lost soul, a historical or legendary figure or Satan, or Satan himself. In many of these stories, from the Wild Hunt of Odin to the spectral coach, the theme of headlessness is present. Henry the Eighth’s allegedly adulterous second wife Anne Boleyn was said to travel in a coach on the anniversary of her execution at Blickling Hall in Norfolk. The disgraced queen sits in a carriage drawn by four headless horses and driven by a headless coachman carrying her own head in her lap.

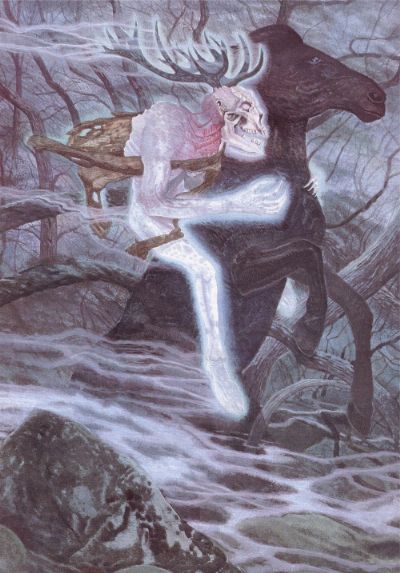

The Master of the Hunt is a tall man, wearing a great grey cloak. Sometimes he is described as wearing a helm with antlers, and sometimes he is described as actually having antlers on his head. The Master rides a great grey horse, of uncertain gender. Its eyes seem to glow with green flames, and sparks are struck from its hooves. The Master carries a great spear, as well as a short bow, with a quiver of hunting arrows that never seems to be exhausted.

Mythological figures

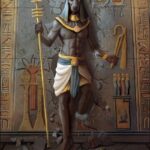

Odin

The Norse god Odin in his many forms, astride his eight-legged steed Sleipnir, was deeply associated with the Wild Hunt, particularly in Scandinavia. Odin’s name is derived from the Old Norse Odhr which means “Fury, ecstasy, inspiration”.

As it was thought that the souls of the dead were wafted away on the winds of a storm, Odin became regarded as the leader of all disembodied spirits – the gatherer of the dead and a pyschopomp. Eventually, storms became associated with his passing. The hunt was known as Odin’s Hunt, the Wild Ride, the Raging Host or Asgardreia and was said to presage misfortune such as pestilence, death or war.

A death allusion might be made from the manner in which a dead man is borne in his coffin, through the air, by four pallbearers with two legs each.

Otto Höfler (1934) and other authors of his generation emphasized the identification of the hunter with Odin, looking for the traces of an ecstatic Odin cult in more recent customs from German-speaking areas.

Berserkers are most commonly associated with the cult of Odin from ninth century Norway onward. By donning animal skins or believing themselves transformed into animals by their rage, they can easily be seen as the hounds of Odin’s Wild Hunt. Witness Snorri’s description:

“[Odin’s] own men went without byrnies, and were as

mad as dogs or wolves, and bit on their shields, and

were as strong as bears or bulls; menfolk they slew,

and neither fire nor steel would deal with them: and

this is what is called Bareserks-gang.”15

Woden

In parts of Germany and Scandinavia the Wild Hunt was known as ‘Woden’s Hunt’. The Wild Huntsman was a demonic figure, who would throw unsuspecting peasants their share of ‘game’ with horrific consequences. This savage and tricky being is generally thought to be an aspect of Woden (from the Saxon Wod), a god who was characterised by his duplicity. Woden is known to be one aspect of Odin. In Germany, these packs of spectral hounds included the souls of unbaptised babies in the train of ‘Frau Bertha’, who sometimes accompanied the Wild Huntsman.

Herla

One of the earliest Wild Hunt tales was written by Walter Map, a Herefordshire man, in about 1190. In it an ancient British King named Herla was about to be married when the King of the Dwarves riding a goat asked if he could come to the wedding. “Sure”, said Herla graciously, and the dwarf asked him in return to come to his a year later. The next year the King of the Dwarves came back to lead the king and his retinue to his place – a cave in a cliff by the Wye. After three days of feasting Herla and his men left with gifts, including a bloodhound which he was to carry on his saddle with him until he chose to jump down. Only then were the king’s men allowed to dismount.

On their way home Herla asked an old shepherd for news of his wife. The Shepherd explained he could only just understand Herla as he was Saxon, but the only woman of that name was the wife of an ancient British King who had disappeared near that very spot centuries ago. Some of Herla’s men choosed to dismount and turned to dust, so Herla and the rest rode on until the bloodhound jumped down – he never did. were thus doomed to wander the earth forever Herla led his men on wandering the earth through the centuries, until the time of Henry II when they reputedly rode into the Wye and vanished.

“This household of Herlethingus was last seen in the marches of Wales and Hereford in the first year of the reign of Henry II, about noonday: they travelled as we do, with carts and sumpter horses, pack-saddles and panniers, hawks and hounds, and a concourse of men and women.

“Those who saw them first raised the whole country against them with horns and shouts, and . . . because they were unable to wring a word from them by addressing them, made ready to extort an answer with their weapons. They, however, rose up into the air and vanished on a sudden.”

Some trace ‘Herle’ back to Herian, a name of Woden/Odin as lord of the troops of warriors (ON herjar) who thronged Valhalla.

Some suggest the element Herle relates to Herian, one of Odin’s many names, and refers particularly to his role as the leader of the dead warrior who filled the Hall of Heroes – Valhalla. In 1123, for example, it was referred to as the familia Herlechini by Ordericus Vitalis. In France it was La Mesnie Herlequin while in England we find Milites Herlewini.

Harlequin

Harlequin (sometimes spelt Herlequin, Harlequin, Hellequin or Hillikin), was refered as the leader in France and Italy. It will become later the driver of the masquerade in the carnival tradition and one of the characters (a trickster) of the Italian Comedia Dell’Arte. The origins of the name are uncertain: some say it comes from Dante’s Commedia (Inferno, XXI, 118) where one of the devils is called Alichino. Others say it could come from Harlenkoenig, a Scandinavian hero. In another hypothesis it comes from Harlay, an English gentleman of the court of Henri III, who had protected an Italian actor. Folk etymology makes “Charles quint” into “Hellekin,” as in the 14th-century “Exposition de la doctrine chretienne”; Last but not least, it would be derived from Herle or Herla.

The expression Map uses to describe the Wild Hunt, the ‘familia Herletbingi’ appears to contain the word ‘thing’ in its Old English sense of ‘troop and would mean ‘the troop of Herle’. Ordericus Vitalis (writing in 1123)the ‘familia Herlechini’, – the household of Herlechinus, just as later in some parts of France it was la Mesnie Herlequin (whence eventually the sixteenth century figure of Harlequin, who first appeared on the Paris stage towards the end of 1135-1204). Peter of Blois, archdeacon of Bath and London calls it milites Herlewini, ‘the troop of Herlewin’, while in the fourteenth-century poem ‘Mum and the Sothsegger’ an unruly rabble is called ‘Hurlewaynis kynne’, – the kindred of Hurlewain.

Walter Map, writing around 1190, tells the story of King Herla, whom he knew as its leader, and later adds:

“The nocturnal companies and squadrons, too, which were called of Herlethingus, were sufficiently well-known appearances in England down to the time of Henry II, our present lord. They were troops engaged in endless wandering, in an aimless round, keeping an awe struck silence, and in them many persons were seen alive who were known to have died. This household of Herlethingus was last seen in the marches of Wales and Hereford in the first year of the reign of Henry II, about noonday: they travelled as we do, with carts and sumpter horses, pack-saddles and panniers, hawks and hounds, and a concourse of men and women. Those who saw them first raised the whole country against them with horns and shouts, and . . . because they were unable to wring a word from them by addressing them, made ready to extort an answer with their weapons. They, however, rose up into the air and vanished on a sudden.”

Cernunnos

The similarity of names associated with the legend– Herla, Hellequin (or Herlequin), Herne– tends to point to a common root, perhaps that of Cernunnos, the Horned God of the witches; prehistoric paintings in the cave of Trois Freres in Saint-Giroud in Ariege, France depict, in the midst of a group of various animals, the figure of a man clad in an animal skin, with horns. Similar cave paintings in South Africa and other places, including one remarkable one from Oued Djaret in the Sahara showing a hunter with an animalistic head followed by a dog, seem to reinforce the image. Recently, the “Pagan” movements have unsuccessfully tried to reinterpret the original myth in a clumsy new age style that mix the Green Man with the Hunter.

Herne

Connection is sometimes made between the Wild Hunt and the legend of Herne the Hunter, a forest keeper of either Richard II or Henry VIII’s time who was charged with poaching and witchcraft, and hung upon an oak in Windsor Forest.

Shakespeare’s Mistress Page refers to this in *The Merry Wives Of Windsor*, Act 4, Scene 4 and has Falstaff dress up as Herne. He too is accompanied by the sound of his horn and the noise of baying hounds, and is a malignant phantom causing ailments of cattle and local misfortune. It has been suggested that Shakespeare (in The Merry Wives of Windsor) moved Herne to Windsor from his original haunt in Feckenham Forest, close to Shakespeare’s Forest of Arden. A guy called Callow (who gave his name to many Midlands places) was also said to lead the Hunt in Feckenham.

“There is an old tale goes that Herne the Hunter,

Sometime a keeper here in Windsor Forest,

Doth all the winter-time, at still midnight,

Walk round about an oak, with great ragg’d horns;

And there he blasts the tree, and takes the cattle,

And makes milch-kine yield blood, and shakes a chain

In a most hideous and dreadful manner.

You have heard of such a spirit, and well you know

The superstitious idle-headed eld

Receiv’d, and did deliver to our age,

This tale of Herne the Hunter for a truth.”

Herne has often been linked to the Celtic god Cernunnos

An appearance of Herne the Hunter in Windsor Forest is followed by tragedy or disaster, often of national importance.

Herne and his pack were considered as erotic and sometimes brutal men, embodying the frightening aspects and wildness of the forests at a time when they were much larger than today and considered to host the pagan spirits that were chased away by the Church.

King Arthur

In another tradition of naming the Huntsman after well-known departed nobles of the time, an account of the late 1100s identifies him as King Arthur, a version corroborated by Gervase of Tilbury in the 13th century (1211), who says that Arthur and his knights regularly hunt an ancient trackway between Cadbury and Glastonbury which is still known as King Arthur’s Causeway. Gervase calls the Hunt ‘familia Arturi’, the household of Arthur, and later in some places in France it was known as ‘la Chasse Artus’ or ‘Arthur’s hunt.

In Scotland, an old rhyme goes:

Arthur o’ Bower has broken his bands

And he’s come roaring owre the lands

The King o’ Scots and a’ his power

Canna turn Arthur o’ Bower.

The Devil

In a process largely described for other categories of monsters, the Church was used to demonizing aspects of the native pagan religions. Naturally, the leader of the hunt became associated Satan, and the hounds were the unfortunate souls of unbaptized children.

Gwynn ap Nudd

In Wales, the leader of the Hunt was Gwynn ap Nudd, the “Lord of the Dead” and the ruler of Annwn (the Underworld). Gwyn means “fair, bright, white” and is cognate with Irish fionn. He is alos known as Arawn, king of Annwm. In later legends Gwyn is king of the tylwyth teg or “fair folk”. He rides with his white, red-eared hounds (the Cŵn Annwn or Hounds of Annwn) through the skies in autumn, winter, and early spring.

The baying of the hounds is identified with the crying of wild geese as they migrate, and the quarry of the hounds are the wandering Otherworld Spirits (possibly fairies), being chased back to Annwn (sometimes to the abode of the Brenin Llwyd or Grey King). Later the relevant mythology was altered to describe the “capturing of human souls and the chasing of “damned souls” to Annwn”; Annwn was inaccurately revised in some variants of Welsh mythology and described as being “Hell.”

In the early Arthurian story Culhwch and Olwen, he abducted a maiden called Creiddylad after she eloped with Gwythr ap Greidawl, Gwyn’s long-time rival. Gwyn and Gwythr’s fight, which began on May Day, represented the contest between summer and winter. He helped Culhwch hunt the boar Twrch Trwyth.

Some of the more prominent myths about Gwyn include the incident in which Amaethon stole a dog, lapwing and a white roebuck from Gwyn, leading to the Cad Goddeu (Battle of the Trees), which Gwyn lost to Amaethon and his brother, Gwydion.

In the Mabinogion, Pwyll mistakenly set his hounds upon a stag, only to discover that Gwyn had been hunting the same animal. To pay for the misdeed, Gwyn asked Pwyll to trade places with him for a year and a day, and defeat Hafgan, Arawn’s rival, at the end of this time, something Arawn had attempted to do, but had been unable to. Arawn, meanwhile, took Pwyll’s place as lord of Dyfed. Arawn and Pwyll became good friends because, though Pwyll wore Arawn’s shape, he slept chastely with Arawn’s wife.

Similar stories can be found with the Fiana and Tuaha de Danann, the fairy people of Ireland

Eckhardt

In Middle and Upper Germany, the man who goes before the host was called “der trewe Eckhardt.” Grimm identifies this figure as Eckhardt, Kriemhild’s chamberer in Nibelungenlied (III, p. 935), and in the Heldenbuch, he is said to sit outside the Venusberg to warn people, much as he does in the accounts of the furious host. By 1534, Eckhart had passed into a proverb: “Du thust wie der trewe Eckhart, der warnet auch jederman vor schaden” (You do like the trusty Eckhart, who also warns everyone of harm).

Harry-ca-Nab

Another phantom huntsman is Harry-ca-Nab who kept his dogs at Halesowen (‘Hell’s Own’ in popular etymology). He would hunt boar mounted on a winged horse or wild bull across the Lickey Hills on stormy nights. To see his hunt presaged ill luck or death.

Historical figures

In the various German, Swedish, and Danish folk tales from the medieval or post-medieval time, the leaders of the Hunt are almost invariably men of high status, either men who abuse their privileges in some manner or commit some form of blasphemy and were doomed for their sins: hunting on a Sunday when he should have been at Church is a common theme. Such tales reinforce the peasant innocence in contrast to the noblemen in power who were used to treat them no much better than preys when hunting through the woods. Then the ghostly procession become a horde of hunters which, with the emphasis on a single, named figure, eventually becomes the solitary hunt which often appears in Swedish and Danish legend.

The theme that the Hunt is led by a nobleman is common to both Scandinavia and Germany. A characteristic example of the story comes from Rugen: a great prince who loved the hunt more than anything else. When a herdboy cut the bark of a young tree to make a pipe, the prince tied the youth’s guts to the tree and chased him about it. A farmer who killed a stag that was eating his corn, the prince bound living to a stag and let the animal run free in the wood until it had battered the man to death. “For such cruel deeds the monstrous man at last got the payment he had earned.” He broke his neck while hunting, “and now it is his punishment after death, that he also has no rest in the grave, but must about the whole night and hunt like a wild monster. This happens every night, winter and summer, from midnight to an hour before sunrise, and then people often hear him crying: ‘Wod! Wod! Hoho! Hallo! Hallo!’, but his usual cry is ‘Wod! Wod!’ and from this he himself is called ‘der Wode’ in many places” (Jahn, Ulrich. Volkssagen aus Pommern und Rügen, pp. 4-5).

The Cornish legend of Tregeagle tells of a cruel and diabolical landowner in life whose spirit is placed in the charge of priests at his death, and who must perform impossible tasks like bailing out the bottomless pool of Dosmery using a limpet-shell with a hole in it, or fashioning ropes of sand, else be chased to Hell by the Devil and his hounds. Tregeagle howls in dismay at his continual failures, and is finally taken to Land’s End, where his cries cannot be heard. ‘To roar like Tregeagle’ became an expression in Cornwall, and there is a Tregeagle ghost story called ‘Nights On Roughtor’ by Donald Rawe in the Denys Val Baker-edited HAUNTED CORNWALL (William Kimber; London 1973, and a UK Heritage paperback from 1980).

Wild Edric

Wild Edric leads the hunt in Shropshire. He led the men of Shropshire against the Normans, but betrayed his cause by making a dodgy peace with William in 1070. He was married to Godda, a faery queen, who disappeared one day. For ever more he is destined to go on galloping furiously across the Stiperstones in search of his wife. He has developed a tendency to appear on the eve of war – he was seen (with Godda for once) on the eve of the outbreak of the Crimean War, and made further appearances in 1914 and 1939.6

Black Vaughan

Related to the theme, perhaps, is the story of Black Vaughan who was beheaded during the War of the Roses. His ghost caused no end of hassle in the Herefordshire Village of Kington until twelve parsons succeeded in trapping it in a snuff box and throwing it into Hergest Pool in the grounds of the Vaughan family’s home of Hergest House. Then the haunting continued in the form of a huge black dog, sometimes holding Vaughan’s head in its mouth. The phantom hound’s howls signalled the impending death of one of the Vaughan family. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle knew the family and based The Hound of the Baskervilles on their story.7,8

Sir Peter Corbet

Sir Peter Corbet, who owned Chaddersley Corbet and much land around Alcester, was another local leader of the Hunt. Edward I gave him a charter to hunt wolves in the royal forests of Gloucestershire, Herefordshire, Worcestershire, Staffordshire, and Shropshire. Hearing of his daughter’s secret meetings with a man in the woods, he locked her in her room and let the hounds out. The suitor was torn to shreds, and his daughter drowned herself in the mor. Peter wasn’t too happy, so he hanged his hounds and threw their bodies in a pool. After his own death in around 1300, he was doomed to roam the forests with his hounds.

Sir Francis Drake

One of the earliest of these ghosts, that of Sir Francis Drake, made repeated journeys over Dartmoor in a black coach driven by headless horses and accompanied by a pack of hounds. Drake occupied the usurped ecclesiastical lands of Buckland Abbey within his natural lifetime, so the development of this ghost story may have received impetus from those who judged the status of his ownership.

Hans von Hackelnberg

A later folktale states that the leader was Hans von Hackelnberg, a semi-historical figure who died in either 1521 or 1581. It was said he had slain a boar and was then injured on the foot by the boar’s tusk and died of poisoning.

As he died he declared that he had no wish to enter heaven, but instead wanted to hunt. His wish was granted and he was permitted, or perhaps cursed, to hunt in the night sky. Another version of the tale has it that he was condemned to lead the Wild Hunt as punishment for his sins.

But even behind this 16th century character, lies a more ancient element, perhaps harking back to the original traditions surrounding the hunt. Hackelnberg, it has been suggested, is simply a corruption of “Hakolberand” – the Old Saxon epithet for Woden.

Adolf Hitler

In Leni Riefenstahl’s “Triumph of the Will”, Hitler is considered as the “a reincarnation of All-Father Odin, whom the ancient Aryans heard raging over the virgin forests”. It ends with “the ethereal passage of silhouetted figures marching heavenwards in the clouds”. The Nazis made great play of their appeal to the Mythic Past to bolster Nationalist feelings in Germany and used Mythology to reinterpret history and serve their social and political purpose.