Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors, and/or as a retainer sacrifice, wherein a monarch’s servants are killed in order for them to continue to serve their master in the next life. Closely related practices found in some tribal societies are cannibalism and headhunting.

Human sacrifice was practiced in many human societies beginning in prehistoric times. By the Iron Age (1st millennium BCE), with the associated developments in religion (the Axial Age), human sacrifice was becoming less common throughout Africa, Europe, and Asia, and came to be looked down upon as barbaric during classical antiquity.In the Americas, however, human sacrifice continued to be practiced, by some, to varying degrees until the European colonization of the Americas. Today, human sacrifice has become extremely rare.

Human sacrifice is typically intended to bring good fortune and to pacify the gods, for example in the context of the dedication of a completed building like a temple or bridge. In ancient Japan, legends talk about hitobashira (“human pillar”), in which maidens were buried alive at the base of or near some constructions to protect the buildings against disasters or enemy attacks, and almost identical accounts appear in the Balkans (The Building of Skadar and Bridge of Arta).

Fertility was another common theme in ancient religious sacrifices, such as sacrifices to the Aztec god of agriculture Xipe Totec. Another purpose is divination from the body parts of the victim. According to Strabo, Celts stabbed a victim with a sword and divined the future from his death spasms.

Human sacrifice can also have the intention of winning the gods’ favor in warfare. In Homeric legend, Iphigeneia was to be sacrificed by her father Agamemnon to appease Artemis so she would allow the Greeks to wage the Trojan War.

Mongols, Scythians, early Egyptians and various Mesoamerican chiefs could take most of their household, including servants and concubines, with them to the next world. This is sometimes called a “retainer sacrifice”, as the leader’s retainers would be sacrificed along with their master, so that they could continue to serve him in the afterlife.

Headhunting is the practice of taking the head of a killed adversary, for ceremonial or magical purposes, or for reasons of prestige. It was found in many pre-modern tribal societies.

History of human sacrifices

Greece

References to human sacrifice can be found in Greek historical accounts as well as mythology. The human sacrifice in mythology, the deus ex machina salvation in some versions of Iphigeneia (who was about to be sacrificed by her father Agamemnon) and her replacement with a deer by the goddess Artemis, may be a vestigial memory of the abandonment and discrediting of the practice of human sacrifice among the Greeks in favor of animal sacrifice.

Sacrifices had various purposes that were even social or political like the wedding ceremony or the ratification of an alliance pact between cities .The ancient ritual of expelling certain slaves, cripples, or criminals from a community to ward off disaster (known as Pharmakos), would at times involve publicly executing the chosen prisoner by throwing them off of a cliff.

Another common situation when sacrificed was used was after marriage. “We know that sacrifices where customary before marriage, and where there is sacrifice there may always be votive offerings. Human sacrifices were also quite popular but seldom represented in art. Slaves and prisoners were the victims of choice among the Greek population.

Rome

According to Pliny the Elder, human sacrifice in ancient Rome was abolished by a senatorial decree in 97 BCE, although by this time the practice had already become so rare that the decree was mostly a symbolic act. Human sacrifice once abolished is typically replaced by either animal sacrifice, or by the mock-sacrifice of effigies, such as the Argei in ancient Rome.

Captured enemy leaders were only occasionally executed at the conclusion of a Roman triumph, and the Romans themselves did not consider these deaths a sacrificial offering. Gladiator combat was thought by the Romans to have originated as fights to the death among war captives at the funerals of Roman generals, and Christian polemicists such as Tertullian considered deaths in the arena to be little more than human sacrifice.

Phoenicia/Carthage

According to Roman and Greek sources, Phoenicians and Carthaginians sacrificed infants to their gods. The bones of numerous infants have been found in Carthaginian archaeological sites in modern times, but their cause of death remain controversial. In a single child cemetery called the “Tophet” by archaeologists, an estimated 20,000 urns were deposited.

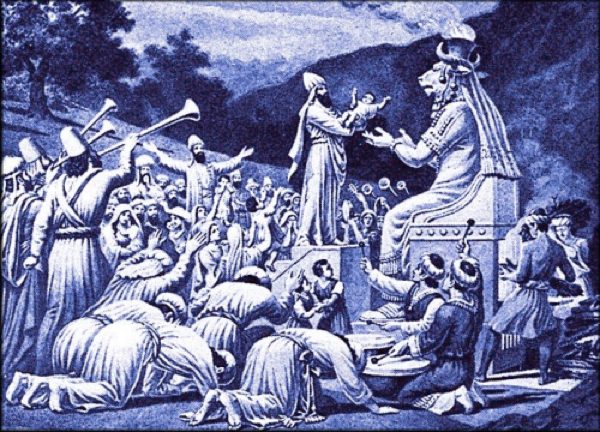

Plutarch (c. 46 – c. 120 CE) mentions the practice, as do Tertullian, Orosius, Diodorus Siculus and Philo. Livy and Polybius do not. The Bible asserts that children were sacrificed at a place called the tophet (“roasting place”) to the god Moloch. According to Diodorus Siculus’s Bibliotheca historica, “There was in their city a bronze image of Cronus extending its hands, palms up and sloping toward the ground, so that each of the children when placed thereon rolled down and fell into a sort of gaping pit filled with fire.” Plutarch, however, claims that the children were already dead at the time, having been killed by their parents, whose consent – as well as that of the children – was required. Tertullian explains the acquiescence of the children as a product of their youthful trustfulness.

Northern Europe

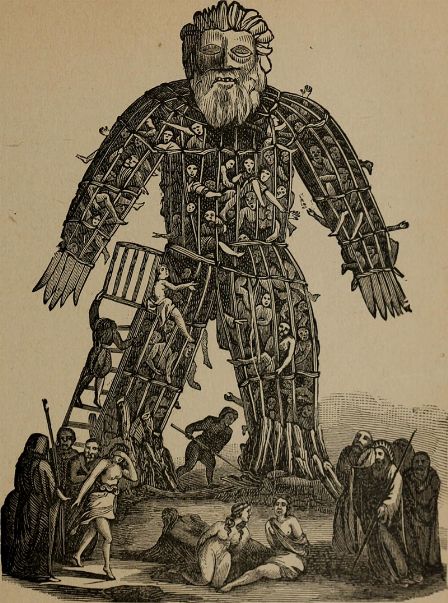

Accounts of Celtic human sacrifice come from Roman and Greek sources. Julius Caesar and Strabo wrote that the Gauls burnt animal and human sacrifices in a large wickerwork figure, known as a wicker man, and said the human victims were usually criminals; while Posidonius wrote that druids who oversaw human sacrifices foretold the future by watching the death throes of the victims.

Caesar also wrote that slaves of Gaulish chiefs would be burnt along with the body of their master as part of his funeral rites. In the 1st century AD, Roman writer Lucan mentioned human sacrifices to the Gaulish gods Esus, Toutatis and Taranis. In a 4th century commentary on Lucan, an unnamed author added that sacrifices to Esus were hanged from a tree, those to Toutatis were drowned, and those to Taranis were burned.

By the 10th century, Germanic paganism had become restricted to the Norse people. One account by Ahmad ibn Fadlan in 922 claims Varangian warriors were sometimes buried with enslaved women, in the belief they would become their wives in Valhalla. He describes the funeral of a Varangian chieftain, in which a slave girl volunteered to be buried with him. After ten days of festivities, she was given an intoxicating drink, stabbed to death by a priestess, and burnt together with the dead chieftain in his boat.

China

Human sacrifice was practiced in China for thousands of years. At a 4,000-year-old cemetery near modern-day Mogou village in northwestern China, archaeologists found hundreds of tombs, some of which held human sacrifices. One sacrificed victim was around 13 years old. Archaeologists have also found thousands of human sacrifices at Shang Dynasty (1600 – 1040 B.C.) sites in the modern-day city of Anyang. More than 13,000 people were sacrificed at Yinxu over a roughly 200-year period, scientists estimate, with each sacrificial ritual claiming 50 human victims on average.

The sacrifice of a high-ranking male’s slaves, concubines, or servants upon his death (called Xun Zang 殉葬 or Sheng Xun 生殉) was a more common form. The stated purpose was to provide companionship for the dead in the afterlife. In earlier times, the victims were either killed or buried alive, while later they were usually forced to commit suicide.

According to the Records of the Grand Historian by Han dynasty historian Sima Qian, the practice was started by Duke Wu, the tenth ruler of Qin, who had 66 people buried with him in 678 BCE. The 14th ruler Duke Mu had 177 people buried with him in 621 BCE, including three senior government officials.

The practice of human sacrifice seems to have stopped or become very rare by the time China was unified in 221 B.C. by Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China. The first emperor’s Terracotta army, made up of thousands of life-size clay warriors, allowed him to take an army with him to the afterlife without sacrificing real-life warriors.

Egypt

Human sacrifice occurred around 5,000 years ago during Egypt’s early history. Human sacrifices have been found by the graves of early pharaohs at Abydos, a city in southern Egypt that served at times as Egypt’s capital and was the cult center for Osiris, the god of the underworld. The practice appears to have become less common or completely phased out by the time the Giza pyramids were built around 4,500 years ago.

Mesopotamia

Retainer sacrifice was practiced within the royal tombs of ancient Mesopotamia. Courtiers, guards, musicians, handmaidens, and grooms were presumed to have committed ritual suicide by taking poison. A 2009 examination of skulls from the royal cemetery at Ur, discovered in Iraq in the 1920s by a team led by C. Leonard Woolley, appears to support a more grisly interpretation of human sacrifices associated with elite burials in ancient Mesopotamia than had previously been recognized. Palace attendants, as part of royal mortuary ritual, were not dosed with poison to meet death serenely. Instead, they were put to death by having a sharp instrument, such as a pike, driven into their heads.

India

In India, human sacrifice is mainly known as Narabali. Here “nara” means human and “bali” means sacrifice. It takes place in some parts of India mostly to find lost treasure. In Maharashtra, the Government made it illegal to practice with the Anti-Superstition and Black Magic Act. Currently human sacrifice is very rare in modern India. There have been at least three cases through 2003–2013 where men have been murdered in the name of human sacrifice.

Human sacrifices were carried out in connection with the worship of Shakti until approximately the early modern period, and in Bengal perhaps as late as the early 19th century. Although not accepted by larger section of Hindu culture, certain Tantric cults performed human sacrifice until around the same time, both actual and symbolic; it was a highly ritualised act, and on occasion took many months to complete.

Over the course of hundreds of years, ending in 1830, an organized crew of dangerous outlaws known as Thugs, or Thuggee, brutally sacrificed more than 30,000 people throughout India. Considered a cult of religious assassins by some, the superstitious Thugs found targets by following natural phenomena they believed to be omens. They ended their targets in a variety of ways, including strangling them with handkerchiefs. The sacrifices were meant to honor Kali, the goddess of creation, preservation, and destruction.

Thugs would disguise themselves as travelers, merchants, or soldiers to gain the trust of their targets. Despite its bloody activities, the cult had a strict code of ethics. According to one source, they were prohibited from sacrificing “fakirs, musicians, dancers, sweepers, oil vendors, carpenters, blacksmiths, maimed or leprous persons, Ganges water-carriers, and women.” However, they would sometimes slay women if it was necessary to maintain the cult’s secrecy.

The practice of Sati (सती) in some Hindu communities, whereby a widow would immolate herself on her husband’s funeral pyre, continued well into the 19th century. Believed to guarantee the couple’s salvation and reunion in the afterlife, it may be seen as a form of retainer sacrifice. India’s Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act (1987)[40] was designed to finally suppress it, as isolated incidents still occurred.

Pre-Columbian Americas

Mayas

The ancient Maya practiced human sacrifice on special occasions. These sacrifices were sometimes conducted in their temples, and many of the victims may have been prisoners of war. At the ancient city of Chichen Itza, victims were painted blue, in honor of the rain god Chaak, before being sacrificed and thrown into a well.

Some archaeologists believe that Maya ball games would, on rare occasions, end with members of the losing or winning team being sacrificed. Evidence for these sacrifices is mainly found in depictions of Maya art, and not all archaeologists interpret the images as representing the sacrifice of a ball team.

The Maya held the belief that cenotes or limestone sinkholes were portals to the underworld and sacrificed human beings and tossed them down the cenote to please the water god Chaac. The most notable example of this is the “Sacred Cenote” at Chichén Itzá. Extensive excavations have recovered the remains of 42 individuals, half of them under twenty years old.

Aztecs

The Spanish conquered the Aztecs during the 16th century, bringing with them diseases that decimated the population. The Spanish sometimes used the Aztec practice of human sacrifice to try to justify their conquest of the Aztecs.

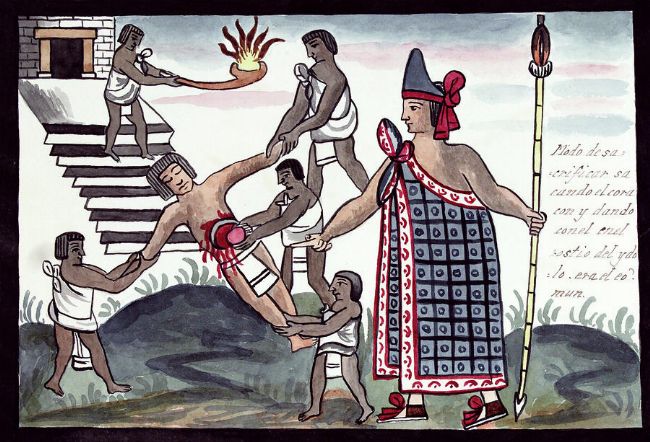

The Aztec civilization in Mexico was centered at the ancient city of Tenochtitlán, in what is now Mexico City, and flourished during the 14th and 15th centuries A.D. Artistic, archaeological and textual records indicate that human sacrifices occurred with some regularity at Tenochtitlán, particularly at the Templo Mayor, one of the largest temples in the city, where the remains of Tzompantli (skull racks) have been found.

The Aztecs, also known as Mexica, were particularly noted for practicing human sacrifice on a large scale; an offering to Huitzilopochtli would be made to restore the blood he lost, as the sun was engaged in a daily battle. Human sacrifices would prevent the end of the world that could happen on each cycle of 52 years.

During the reign of the Aztecs, an estimated 250,000 people were sacrificed across Mexico during an average year. In the 1487 re-consecration of the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan some estimate that 80,400 prisoners were sacrificed though numbers are difficult to quantify, as all obtainable Aztec texts were destroyed by Christian missionaries during the period 1528–1548. They also sacrificed children as it was believed that the rain god, Tlāloc, required the tears of children.

The bodies of the sacrificed were often baked with corn and shared among the priests for a feast. Other times, enough was prepared for the whole city, and every person present would partake in a shared act of ritualistic cannibalism. The bones were then fashioned into tools, musical instruments, and weapons.

South America

The Inca of Peru also made human sacrifices. As many as 4,000 servants, court officials, favorites, and concubines were killed upon the death of the Inca Huayna Capac in 1527, for example. A number of mummies of sacrificed children have been recovered in the Inca regions of South America, an ancient practice known as qhapaq hucha. The Incas performed child sacrifices during or after important events, such as the death of the Sapa Inca (emperor) or during a famine. There were also ceremonies where Moche warriors would engage in ritual combat and those defeated in battle would be bled to death and their blood offered to the principal deities in order to please and placate them.

West Africa

Sacrifices were particularly common after the death of a King or Queen, and there are many recorded cases of hundreds or even thousands of slaves being sacrificed at such events. Sacrifices were particularly common in Dahomey, in what is now Benin. According to Rudolph Rummel, “Just consider the Grand Custom in Dahomey: When a ruler died, hundreds, sometimes even thousands, of prisoners would be slain. In one of these ceremonies in 1727, as many as 4,000 were reported killed. In addition, Dahomey had an Annual Custom during which 500 prisoners were sacrificed.” Human sacrifice is still practiced in West Africa.

The Leopard men were a West African secret society active into the mid-1900s that practised cannibalism. It was believed that the ritual cannibalism would strengthen both members of the society and their entire tribe. In Tanganyika, the Lion men committed an estimated 200 murders in a single three-month period.

Human sacrifices today

Modern secular laws treat human sacrifices as tantamount to murder and most major religions in the modern day condemn the practice. However, human sacrifice is still practiced in Africa and Americas for folk religious or superstitious reasons, despite being illegal. People are allegedly sacrificed by witch doctors to bring wealth to their customers and even to help politicians win elections.

Among the thousands of people that disappear every year in Western countries, there might be a good number that were sacrificed/eaten/bloodshed and carefully disposed of.

Some sects and satanist groups also advocate for human sacrifices. This is the case of the infamous Order of the Nine Angles (ONA).

The ONA’s writings condone and encourage human sacrifice, referring to their victims as opfers. The ONA outlines their guidelines for human sacrifice in a number of documents: “A Gift for the Prince – A Guide to Human Sacrifice”, “Culling – A Guide to Sacrifice II”, “Victims – A Sinister Exposé”, and “Guidelines for the Testing of Opfers”.

According to the ONA’s beliefs, the killer must allow their victim to “self-select” themselves; this is achieved through testing the victim to see if they expose perceived character faults. If this proves to be the case, the victim is believed to have shown that they are worthy of death, and the sacrifice can commence. Those deemed ideal for sacrifice by the group include individuals perceived as being of low character, members of what they deem “sham-Satanic groups” like the Church of Satan and Temple of Set, as well as “zealous, interfering Nazarenes”, and journalists, business figures and political activists who disrupt the group’s operations. The ONA explains that because of the need for such “self-selection”, children must never be victims of sacrifice. Similarly, the ONA “despise animal sacrifice, maintaining that it is much better to sacrifice suitable mundanes given the abundance of human dross”.

The sacrifice is then carried out through either physical or magical means, at which point the killer is believed to absorb power from the body and spirit of the victim, thus entering a new level of “sinister” consciousness.[138] As well as strengthening the character of the killer by heightening their connection with the acausal forces of death and destruction, such sacrifices are also viewed as having wider benefits by the ONA, because they remove from society individuals whom the group deems to be worthless human beings. However, no ONA nexion cells publicly admitted to carrying out a sacrifice in a ritual manner, but that members had joined the police and military groups in order to engage in legal violence and killing.

ONA’s advocacy of human sacrifice has drawn strong criticism from other Satanist groups like the Temple of Set, who deem it to be detrimental to their own attempts to make Satanism more socially acceptable within Western nations.