Witch hunts still occur today.

Africa

Witch-hunts against children were reported by the BBC in 1999 in the Congo and in Tanzania, where the government responded to attacks on women accused of being witches for having red eyes. A lawsuit was launched in 2001 in Ghana, where witch-hunts are also common, by a woman accused of being a witch. Witch-hunts in Africa are often led by relatives seeking the property of the accused victim.

Amongst the Bantu tribes of Southern Africa, the witch smellers were responsible for detecting witches. In parts of Southern Africa several hundred people have been killed in witch hunts since 1990.

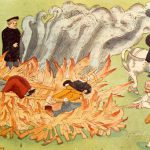

The Congolese Human Rights Observatory recently announced that more than 60 people had been burned or buried alive in that country since 1990 – including 40 in 1996. The victims were accused, often by members of their own family, of being witches.

Several African states, Cameroon, Togo for example, have reestablished witchcraft-accusations in courts. A person can be imprisoned or fined for the account of a witch-doctor.

It was reported on 21 May 2008 that in Kenya a mob had burnt to death at least 11 people accused of witchcraft.

In March 2009 Amnesty International reported that up to 1,000 people in the Gambia had been abducted by government-sponsored “witch doctors” on charges of witchcraft, and taken to detention centers where they were forced to drink poisonous concoctions. On May 21, 2009, The New York Times reported that the alleged witch-hunting campaign had been sparked by the Gambia’s President Yahya Jammeh.

India

In the Telangana region of India, villagers have lately burnt or stoned to death several people suspected of practising ‘Banamati’, a local form of witchcraft, and held responsible for the death and ill-health of several villagers.

Traditionally, local people would remove the teeth of suspected witches in the belief that it would take away their powers. A recent survey by sociologists in Ranga Reddy district and other areas revealed that several factors including illiteracy and lack of medical awareness had contributed to the problem.

In India, labeling a woman as a witch is a common ploy to grab land, settle scores or even to punish her for turning down sexual advances. In a majority of the cases, it is difficult for the accused woman to reach out for help and she is forced to either abandon her home and family or driven to commit suicide.

Most cases are not documented because it’s difficult for poor and illiterate women to travel from isolated regions to file police reports. Less than 2 percent of those accused of witch-hunting are actually convicted, according to a study by the Free Legal Aid Committee, a group that works with victims in the state of Jharkhand.

Between 2001 and 2006, police have reports of over 700 women being killed as witches or witch doctors in eastern India alone. But they believe that the actual number could be many times higher.

A 2010 estimate places the number of women killed as witches in India at between 150 and 200 per year, or a total of 2,500 in the period of 1995 to 2009. The lynchings are particularly common in the poor northern states of Jharkhand, Bihar and Chattisgarh. A Jharkhand case publicized in international media in 2009 concerned five Muslim women.

Papua New Guinea

Though the practice of “white” magic (such as faith healing) is legal in Papua, the 1976 Sorcery Act imposes a penalty of up to 2 years in prison for the practise of “black” magic. In 2009, the government reports that extrajudicial torture and murder of alleged witches – usually lone women – is spreading from the Highland areas to cities as villagers migrate to urban areas.

Saudi Arabia

On February 16, 2008 a Saudi woman, Fawza Falih, was arrested and convicted of witchcraft and now faces imminent beheading for sorcery unless the King issues a rare pardon. And on November 9, 2009, Lebanese TV presenter Ali Sibat (who was arrested in Medina in 2008) was sentenced to death on charges of witchcraft.

According to Sarah Leah Whitson, the Middle East director at Human Rights Watch, “Saudi courts are sanctioning a literal witch hunt by the religious police.” Also according to Human Rights Watch, two other people have been arrested on similar charges in November 2009 alone.

United Kingdom

Occasional prosecutions under the Witchcraft Act (an act designed to eradicate belief in Witches which prohibits claiming to be a witch, not actually being one) continued in 19th and 20th century Britain. A well-publicised recent case was that of the medium Helen Duncan in 1944.

After revealing during a séance the sinking of a ship (HMS Barham} which the Royal Navy had not made public, she was arrested under the Vagrancy Act 1824 and the accusations in court centered round defrauding the public. She spent nine months in prison. The last conviction under the Act was that of Jane Rebecca Yorke. The Act was repealed in 1951 and replaced with the Fraudulent Mediums Act 1951.

This act prohibited a person from claiming to be a psychic, medium, or other spiritualist while attempting to deceive and to make money from the deception (other than solely for the purpose of entertainment).

United States of America

In 1878, more than 40 Navajo witches were killed or “purged” by tribe members because the Navajo had endured a horrendous forced march at the hands of the U.S. Army in which hundreds were starved, murdered, or left to die. At the end of the march, the Navajo were confined to a bleak reservation that left them destitute and starving.

The gross injustice of their situation led them to conclude that witches might be responsible, so they purged their ranks of suspected witches as a means of restoring harmony and balance. Tribe members reportedly found a collection of witch artifacts wrapped in a copy of the Treaty of 1868 and “buried in the belly of a dead person.” It was all the proof they needed to unleash their deadly purge.

The McMartin preschool trial of 1984 to 1990 is the longest trial currently recognized in American history. The victims were accused of satanic ritual abuse in underground tunnels, involving flying witches, actor Chuck Norris, blood drinking, mutilated corpses, and human sacrifice. More than 350 people were involved in the fabrication of the allegations, which were taken seriously by the media, the public, the courts, and the prosecution. The jury did not believe the allegations, however, and the victims were freed.