In 1324, a French bishop, Richard Ledrede, who was working in Ireland, accused Alice Kyteler, of performing witchcraft. Obtaining evidence by having his men whip one of her servants, Petronilla de Meath (who was subsequently burnt at Kilkenny at the instance of Richard, Bishop of Ossory), he claimed that she had met with a group of eight women and four men at night to deny Christianity and cut up living animals in order to scatter their remains at crossroads, as offerings to a demon. Kyteler fled to England in order to survive punishment, but many of the influential locals were angry at Ledrede’s activities, and in 1329 the Bishop of Dublin excommunicated him, forcing his return to France.

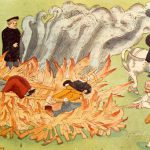

In a witch trial on a large scale carried on at Toulouse in 1334, out of sixty-three persons accused of offences of this kind, eight were handed over to the secular arm to be burned and the rest were imprisoned either for life or for a long term of years. Two of the condemned, both elderly women, after repeated application of torture, confessed that they had assisted at witches’ sabbaths, had there worshipped the Devil, had been guilty of indecencies with him and with the other persons present, and had eaten the flesh of infants whom they had carried off by night from their nurses.

Persecution continued through the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, and the Protestants and Catholics both continued witch trials with varying numbers of executions from one period to the next. The “Caroline Code”, the basic law code of the Holy Roman Empire (1532) imposed heavy penalties on witchcraft.

During this period, the biggest witch trials where held in Europe, notably the Trier witch trials (1581–1593), the Fulda witch trials (1603–1606), the Würzburg witch trial (1626–1631) and the Bamberg witch trials (1626–1631).

A pamphlet called “True and Horrifying Deeds of 63 Witches” records the trial and burning of witches in the imperial lordship of Wiesensteig in southwestern Germany in 1563.

In 1590, the North Berwick witch trials occurred in Scotland, and were of particular note as the Scottish king, James VI, himself got involved and set up royal commissions to hunt down witches in his realm, recommending torture in dealing with suspects, and in 1597 he subsequently wrote a book about witches entitled Daemonologie.

Whilst the witch trials had begun to fade out across much of Europe by the mid 17th century, they continued to a greater extent on the fringes of Europe and in the American colonies. In Scandinavia, the late 17th century saw the peak of the trials in a number of areas; for instance, in 1675, the Torsåker witch trials took place in Sweden, where seventy-one people were executed for witchcraft in a single day. In the nearby Finland, which was then under the control of the Swedish monarchy, the hunt peaked in that same decade.

During the early 18th century, the practice subsided. Jane Wenham was among the last subjects of a typical witch trial in England in 1712, but was pardoned after her conviction and set free. The last execution for witchcraft in England took place in 1716, when Mary Hicks and her daughter Elizabeth were hanged. Janet Horne was executed for witch craft in Scotland in 1727.

The Witchcraft Act of 1735 saw the end of the traditional form of witchcraft as a legal offence in Britain, those accused under the new act were restricted to people who falsely pretended to be able to procure spirits, generally being the most dubious professional fortune tellers and mediums, and punishment was light.

In the later 18th century, witchcraft had ceased to be considered a criminal offense throughout Europe, but there are a number of cases which were not technically witch trials which are suspected to have involved belief in witches at least behind the scenes. Thus, in 1782, Anna Göldi was executed in Glarus, Switzerland, officially for the killing of her infant, a ruling at the time widely denounced throughout Switzerland and Germany as judicial murder.

The McMartin preschool trial of 1984 to 1990 is the longest trial currently recognized in American history. The victims were accused of satanic ritual abuse in underground tunnels, involving flying witches, actor Chuck Norris, blood drinking, mutilated corpses, and human sacrifice. More than 350 people were involved in the fabrication of the allegations, which were taken seriously by the media, the public, the courts, and the prosecution. The jury did not believe the allegations, however, and the victims were freed.